Documentary Photographer, Photojournalist, Humanitarian

“Photography is honest and compelling. Photojournalism is photography to the next level – telling the story of all we are as a species, what we are capable of – both good and bad – exposing the deepest truths within, and creating an uncompromising tale of life existing all around us.” – Dawn Garcia

When I first discovered Ryan Spencer Reed’s work, I was drawn in by his work in the Sudan. The civil unrest, and the continual strife Africa has endured over the decades has been an issue very close to my heart. To the genocide in Rwanda and now to the continual struggles in Darfur, any journalist who has the opportunity to go into that country and seek out the hope, the sadness, the neglect, the war, the triumphs in between, the survival of spirit, and the constant cry to both be heard and be given proper aid – well, those journalists speak to my soul. Ryan is one such journalist. In 1998 I wrote a short story about the genocide in Rwanda. Soon after I began writing a book and film about the genocide. After reading countless accounts written by photojournalists like Ryan, I was compelled to write the story. It’s been 15 years and I’m writing it still. I have had to take pause in the process simply because the topics were so horrific, I couldn’t afford to be careless. Ryan’s work is crucial in the realm of photography, art, social and political healing, and above all crucial to us as a species. Having a deep social consciousness to better mankind and tell the story of who we are and what is happening all around us – that is precisely why I chose him to be one of the Photographers featured in the first ever dedicated Arts + Photography Issue of ATOD Magazine.

Ryan creates works of photography, compelling works of journalism, and harnesses this uncanny sense of social responsibility. It is impossible to ignore the hope situated beneath the truth of what he reveals. He puts his life on the line every time he goes on assignment and he is among those I have been privileged to know such as Tim Hetherington and Sebastian Junger. Ryan’s work speaks in a voice that is haunting, tragic, soaring with honesty, yet in the shadows of his work exists this cry of hope. As if the shrieking voices of those he’s met invite him to believe in the goodness of humanity. We are a lost species capable of atrocity but there is beauty and good that does exist and if we can listen long enough to find the blip in the process, we will rise to the occasion and hopefully, one day – atrocity will be a word we fail to understand merely due to its scarceness. As a writer and someone who believes that everyone has a story that must be told, I have to thank Ryan from the depths of my soul for being unafraid to bear witness to so much displacement and political unrest, to finding beauty in the unknown, to experiencing the gift of humanity and seeking out a justice that is unspoken and actionable. We live in a world that needs to believe in truth but we must harness the hate and create a different current.

Ryan Spencer Reed – Photojournalist | Photographer

“All that is necessary for evil to triumph is for good men to stand by and do nothing.

18th century parliamentarian, Edmund Burke

Ryan will be heading to Afghanistan to work on the following Project:

“Beginning this spring I will embed with my cousin’s unit – 1-506th Infantry Regiment, 4 BCT, 101st Airborne – for the duration of their deployment to Afghanistan. We grew up together and are very close. His is the ‘Band of Brothers‘ regiment. Their deployment timelines dictate that they will be the last to turn out the lights on US conventional military operations in Afghanistan.”- Ryan Spencer Reed

OFFICIAL WEBSITE: www.ryanspencerreed.com | FACEBOOK

OUR INTERVIEW

ATOD – Dawn Garcia (DG) – Your work has an ever-present flow of humanitarianism. What would you say your most pivotal moment as a

photojournalist has been?

Ryan Spencer Reed (RSR): Once in a village in what is now South Sudan, I was presented with photographing the body of a dead infant in the arms her mother and surrounded by the family in a kind of funeral procession. I was not comfortable with the thought of photographing them. I was concerned with their feelings – concerned by my presence. I was a trespasser in their misery. As the procession of mourners began to enter a tiny hut to prepare the body for burial, I began to make my exit, however my presence was requested with gestures by elders. I decided to enter the hut on their urging and I empathetically confront the mother. When our eyes met with my camera in view it was apparent that she understood the purpose in my being there. I understood then that she would welcome me because she wanted her daughter’s death to serve something greater than itself. This moment instilled in me the relationships required to do this work, but also that those relationships often have a head start in some of the most difficult circumstances.

DG: How would you describe the state of the world as you see it through your lens?[/question]

RSR: Fragile and nuanced.

DG: Your recent work, “Shades of Grandeur” really delves into the encompassing demise of the Industrial Revolution and the fall of the American Dream. What site has been the most impacting in terms of polarizing that?

RSR: Detroit as a community on the whole has been the most informing of this evolution for me. It is a place which

rewarded the honor in working with one’s hands only a couple generations ago, yet now it stands symbolic of the

manner by which we have dispelled with our regard for the worker. It is a place where the parasite of human greed

has devoured its host.

DG: How many times have you been to Africa and where have you gone?

RSR: I’ve traveled to Africa five times from the states through parts of South Africa, Kenya, Chad, Sudan, Rwanda, and Egypt.

DG: What was the most disheartening story you’ve encountered?[/question]

RSR: I must apologize but I am not prepared to relive my experiences and choose one representative of something I most desperately want to forget.

DG: What is the most uplifting story you’ve encountered?

RSR: There have been so many uplifting encounters … that has truly been the most rewarding part of my work. The dichotomy of the highs and lows has provided anchors holding me to a path I set out to walk in my life. One such high that immediately comes to mind: While spending some time photographing in India, I met a man born without hands or feet. I found him in the city of Kochi kneeling on a foot bridge drawing on the pavement with the implication that people passing by would offer him some small change for his efforts. He would pinch the chalk between his wrists moving with purpose to create the most incredible likenesses of Hindu deities. I watch for awhile and made some pictures. He did well in donations that day, we spoke briefly when he had finished while he wiped the sweat from his face, I gave him my small offering and went along my way. Several days later I encountered another crowd on the same footbridge and, seeking a familiar face, went to see his work of the day. I found him again working chalk into pavement, only this time with his son who was missing the same body parts as his father. When they finished their spectacular collaboration, the man knelt next to son, balancing on the end of his legs, and they both beamed with pride to take a bow when met with applause.

DG: What is your fondest childhood memory?

RSR: Rafting the Colorado River through the Grand Canyon with my father.

DG: What is your favorite museum?

RSR: My wife and I are museum junkies. I love Chicago’s Art Institute and the International Center of Photography.

DG: What makes you smile?

RSR: My bird.

DG: What gives you hope?

RSR: The perseverance of the human spirit. There seams to be an irreducible human element that many are, due to war and other crises, unfortunately forced to muster. It gives me hope to expect that we are all may be connected by this facet of our make up and that this may assist us in overcoming all obstacles to our survival. I hope I too contain this strength I’ve seen in others.

DG: What is your favorite beer? Cocktail? Wine?

RSR: Beer: I love many balanced craft styles, but due to family obligations, I must say Budweiser in all public forums.

Cocktail: Mojito,

Wine: Pinot Noir and Shiraz (on the drier side).

DG: What sound makes you feel alive?

RSR: Absolute silence.

DG: Do you think American ideal has died?

RSR: I do not think it has died. Rather I feel as though it continues to evolve and therefore looks different than it did to our forefathers. I am struggling to understand how it has left so many behind.

DG: What is your favorite song?

RSR: This is an impossible question for me to answer with one song. I love a wide spectrum of music, but occasionally a piece, when heard for the first time, has a way of getting into the fibers of my feelings at a very primal level as if it causes something I’ve experienced to resonate – something already inside me, but had escaped me until that moment. It is a revelation that can often be experienced again each time the piece is played and feels as real as anything I’ve lived through. I can tell you that much of what Beethoven made gets me in that way. I often fall in love with soundtracks, perhaps because they are made to be paired with, or accentuate, imagery. I enjoy much of Hans Zimmer‘s body of work. Lisa Gerrard‘s too. The piece “Vide Cor Meum” from the film “Hannibal” is one of the best examples of this. “Gortoz A Ran” from the Blackhawk Down soundtrack is another. Like imagery, music can be a universal language.

DG: Darkroom or digital?

RSR: Darkroom.

DG: The human essence is it’s ability to struggle through adversity and triumph in spirit. Do you see humanity rising to

the occasion?

RSR: I absolutely do.

DG: When did you first pick up a camera and know it was what you were meant to do?

RSR: This happened for me in college. I enrolled to study medicine and physics, and acquired photography as a hobby from my three photographer uncles. Learning about the influence images from the Vietnam War had on our nation’s collective conscience, began my vocational interest in using photography as a tool for the expression of things important to me. James Nachtwey’s long commitment to critical social issues had a profound influence on the direction of my life. It was an evolutionary process driven by multiple influences and opportunities, but the camera, for me, is only an implement to justify a commitment to a pilgrimage of conscience.

Photography: Passion? Or purpose?

RSR: Purpose.

DG: What is your go-to movie when you want to watch something utterly pointless?

RSR: Roadhouse is always great for a laugh with my friends.

DG: What is your guilty pleasure?

RSR: Long showers.

DG: What makes you laugh from your gut?

RSR: Usually my cousins are good for this.

DG: Who inspires you?

RSR: My dad, my wife, Raphael Lemkin, Paul Rusesabagina, Aung San Suu Kyi, Nelson Mandela, Mahatma Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr., and Rosa Parks to name a few.

DG: If you could work alongside anyone both living or dead, who would it be and why?

RSR: I would want to be able to work alongside Leonardo da Vinci. I have always found I feel most alive when I am the most challenged and I know I would have found immense joy in trying to keep up with a mind like that … and failing.

DG: A moment in history you believe humanity stepped up?

RSR: The Cuban Missile Crisis was one such moment … so was Rosa Parks’s defiance.

DG: Your last meal would be …?

RSR: Really good Sushi.

Before delving into his collection of work that reaches into a place within so deep that its approximation is unknown – simply because it is a reflection of all we are, all we are capable of, and all we have experienced – I must thank Ryan Spencer Reed. Thank you for being so candid, for doing work that not only do I admire but feel is essential to humanity. You are necessary in this world. Your work is profoundly impacting and the things you have seen and experienced have given you the remarkable ability to tell the world about all you’ve seen and felt. You are a gift to the embodiment of journalism and I for one and honored to be able to tell a bit of your story. Thank you.

His Collections:

(content from www.RyanSpencerReed.com)

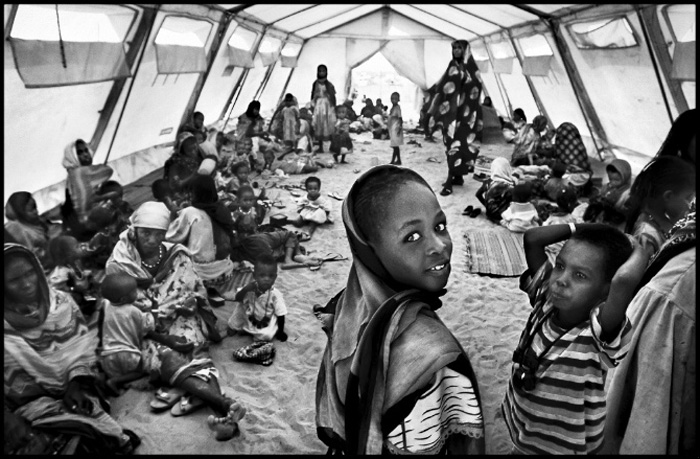

SUDAN: The Cost of Silence.

In the wake of nearly three decades of brutal civil war, the population of South Sudan lies shattered and strewn across the Central and East African landscape. More than two and half million people have been killed and another five million have been internally and externally displaced by the conflict. As of July of 2011, South Sudan has achieved its independence, seceding from its oppressors and has become the newest nation on the planet. Since January of 2003, however, a new exodus flooded the western border region of Darfur in Sudan with displaced persons fleeing the same regime responsible for the southern tragedy. Despite the fact that the United States has formally labeled this diaspora genocide, the killing continues unchecked, threatening to shed blood on every grain of sand. In the words of former U.S. President Clinton, “If the horrors of the Holocaust taught us anything, it is the high cost of remaining silent and paralyzed in the face of genocide.”

DETROIT: Forsaken

Motor Cityâs stage for Tommy Dorsey, Duke Ellington, Benny Goodman and other musical giants: The Vanity Ballroomâs now hollow dance floor suggests the opulence provided by the manufacturing spoils of the 1930s and 40s. (12/6/09)

Caption:

A grand ballroom inside the Lee Plaza Hotel echoes Motown’s glory days. A now silent piano, performed for hotel guests and those living in luxury apartments, remains shrouded by boarded windows. (10/31/09)

The remains of the original Detroit Tiger’s stadium, located on Michigan Avenue, were cleansed by a thunderstorm during its final day’s stay of execution. The stadium was torn down by late summer 2009, ten years after the last runner touched home plate. Its replacement was renamed “Comerica Park” after the national bank which got its start as the “Detroit Savings Fund Institute” in 1849. Comerica’s relocation of their corporate headquarters to Dallas, Texas in 2007 implies their position on the outlook for the future of Detroit. (5/27/09)

Shades of Grandeur

Shades of Grandeur: This is my America – today – evolving rapidly as it remains caught in the wake of unsustainable business practices and policy following the aftermath of World War II. Nearly devoid of the human form, these images unveil an adaptation of the phrase, the Arsenal of Democracy, because the city of Detroit, and all that it symbolized, no longer resembles any such thing. The term is more befitting of the nationstate more broadly disseminating values, and placing much focus of policy, globally.

These images are a product of a pilgrimage to rediscover things left behind through the dim and murky light of history. Some are filled with symbols while others are simply about conveying mood. They are an attempt to tell a story of a nation amidst the death of the American Industrial Revolution, when ambitions of empire and the specter of hubris pull at a superpower in transition – at odds with itself and gasping for compass beyond the precipice of shifting paradigm.

After the war, US factories returned relatively simply and quickly to making civilian products. With little global competition, as a result of having the only industrial complex to have survived the war, the country was ushered through a period of unprecedented growth and unsustainable profits during the 20 years following the Great War. And, while many US companies received contracts to rebuild the infrastructures of other nations, American industrial infrastructure outgrew the economic foundation of demand that would need to support it once the rest of the world’s factories came back online.

Once the US economy began to plateau through the mid 1960s, some two decades of prosperity had shifted expectations and created a false positive of what was possible for the American dream. Most concluded that those years were the norm and ultimately something had to be done to sustain those levels of growth. Wall Street’s demand for continued positive quarterly company reports drove many boardrooms to look to labor for additional profit margins. The trend of outsourcing, off shoring, selling off, and eventual dismantling of the American industrial complex, reflected an underlying shift in values within American society.

For generations, the economy has attempted to outrun a much needed correction to American expectations and way of life. The chain of events has caused the country to prematurely end to its industrial revolution leaving behind a systemic stigma that there is little honor left in working with one’s hands as an American. The society must learn to cope with a legacy of power, dominance, and hubris. If this story is symbolic of a country’s misspent youth, then the revelation of peak oil, and the long overdue correction to the bubbles that formed following the Great War mark the harsh wakeup call that is adulthood.

The American experiment has been a monolith of human achievement. Few nations have had more influence on the growth of human civilization. However, the recent economic volatility casts an ominous tone over a great many civilizations that aspire to the American level of opulence. What remains are apparitions of empire – haunting, seductive and alive with ghosts.

These are a sample of images from a project which explores the themes of empire and hubris using symbols of American history beside images of modern day Americana. More on this work here: www.RyanSpencerReed.com

ABOUT

Ryan Spencer Reed (b. 1979) is an American photographer whose journey documenting critical social issues began shortly after college when he self-financed a move to east Africa. Working in that region and covering the Sudanese Diaspora for nearly 7 years, Ryan has entered Sudan a half dozen times in addition to covering the mass exodus of refugees to Eastern Chad and Kenya. In late summer 2004, he returned from covering the War in Darfur to produce that body of work for distribution. This work was widely exhibited in the States and abroad. The Soros Foundation’s Open Society Institute awarded him with the Documentary Photography Project’s Distribution Grant in 2006 to help this work reach additional audiences. While exhibiting and speaking internationally on the subject of Sudan, he has begun a long-term project on the hubris of power and the twilight of the American industrial revolution. A chapter of this work on Detroit is currently being distributed.