Photos by Dawn Garcia

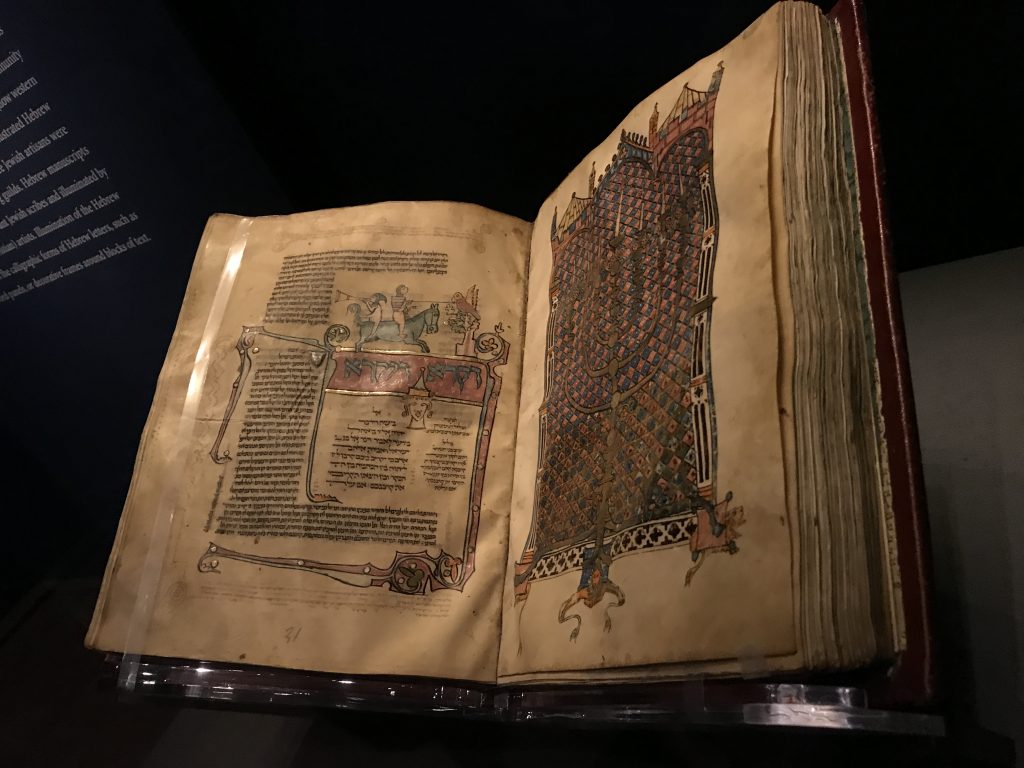

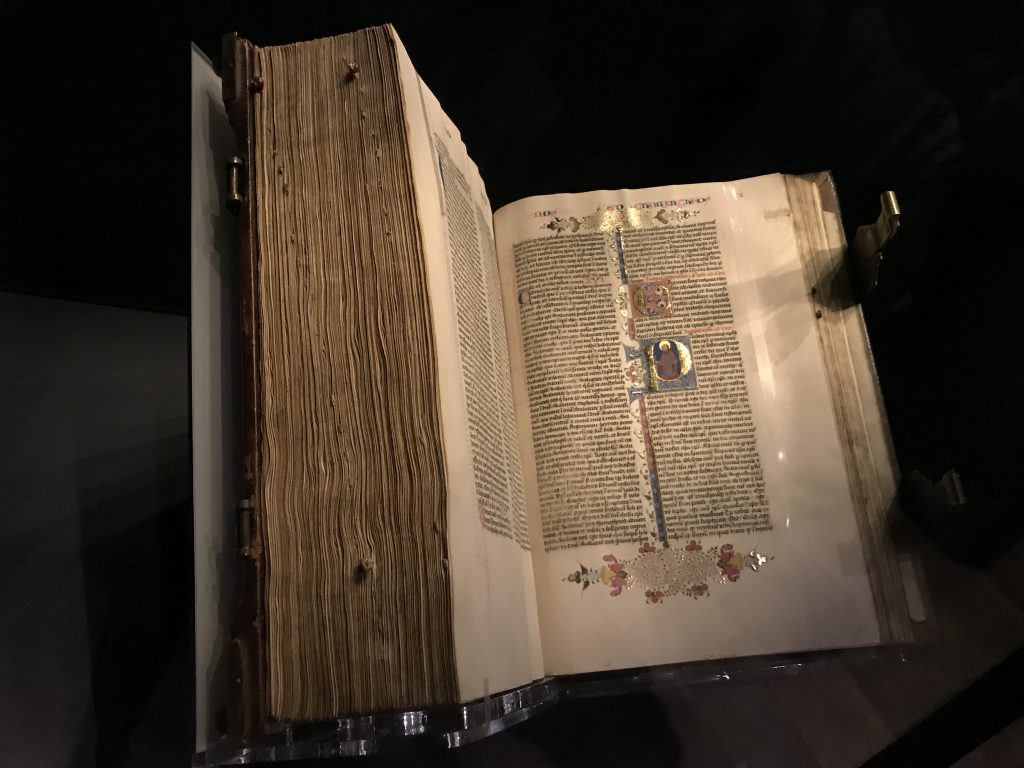

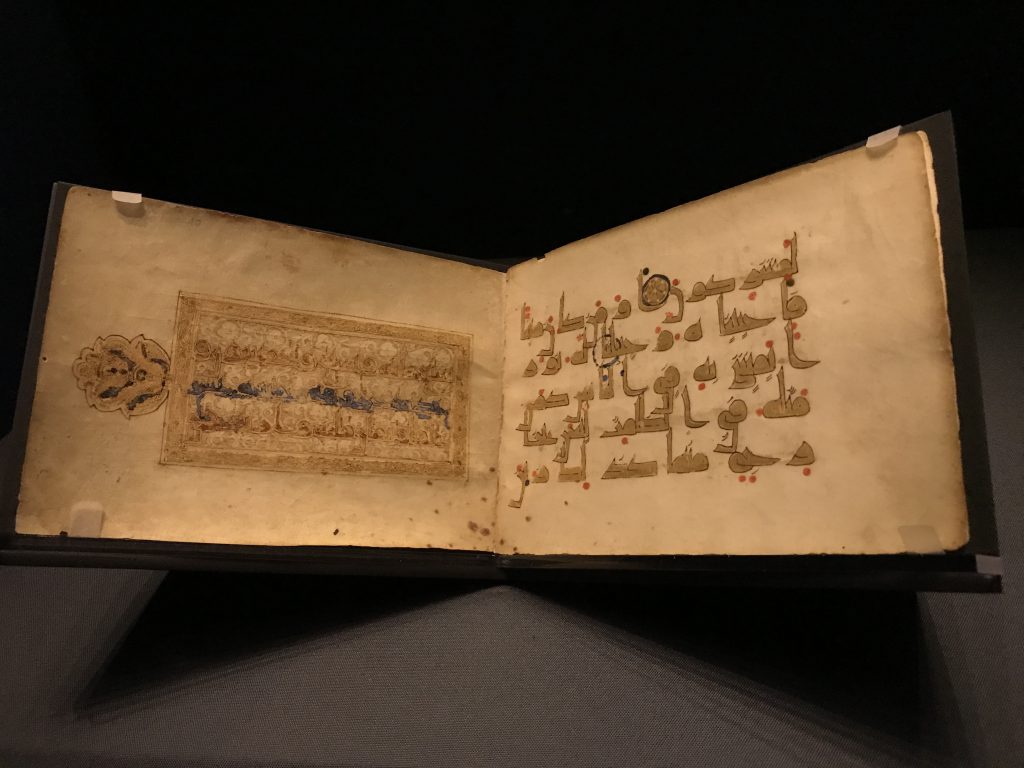

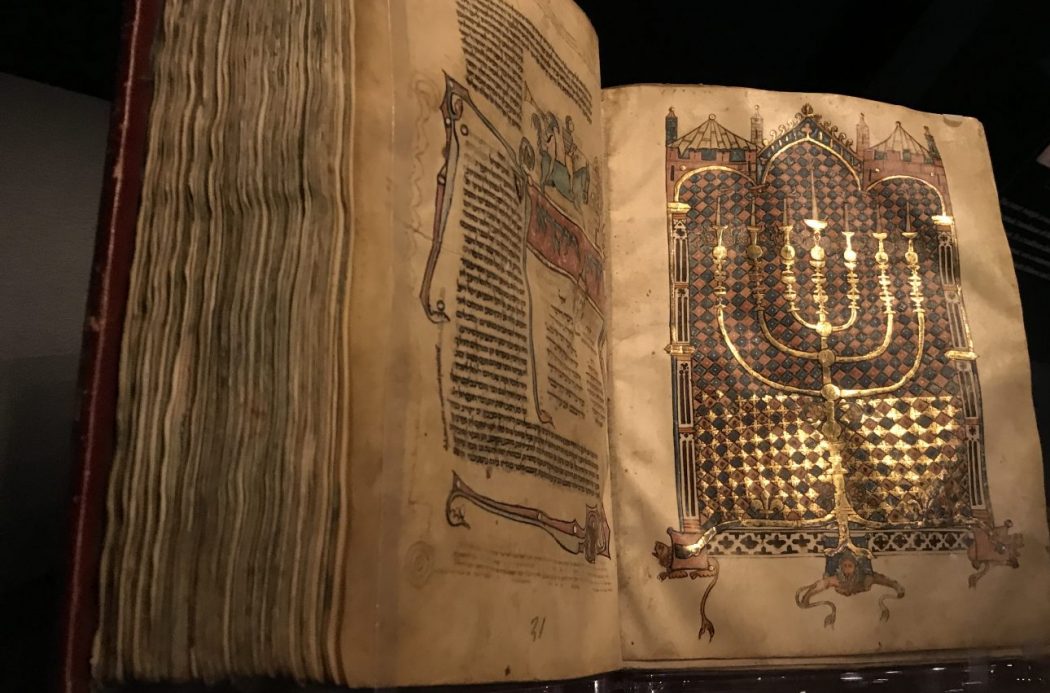

In a world that seems to be unraveling one news story or act of violence at a time, the Getty Museum’s devoted team of those researching and seeking rare manuscripts have curated an exhibition, Art of Three Faiths, that brings the world together in one unified space. With three rare manuscripts from the Middle Ages, three faiths are honored with a 1296 Torah manuscript (Judaism), a Hebrew Bible dating back to 1450 (Christianity), and a Qur’an from Tunisia dating back to the ninth century (Islam).

The Getty Museum | 1200 Getty Center Drive | Los Angeles

When you arrive at the exhibition, one must pause. Far too often beliefs are used as a means of segregation but here, there is only oneness. That is evident in the beauty of the meticulously hand written manuscripts down to the way in which they’ve preserved over time. The space itself lends to the striking universality of its message: People of the Book.

As simple as it may seem, those words are powerful and impactful. They don’t simply imply a sense of unity, they empower and embody the notion that perhaps its time we all value one another more purely.

The Getty explains that this “acquisition allows the Getty—for the first time—to represent the medieval art of illumination in sacred texts of the three Abrahamic religions—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, founded in that order.” And when you witness the intricacies and the passages of so many bygone eras in person, in a very intimate space, you’ll be remiss not to want to revel in every bit of it.

“We did a presentation earlier this year through the lens of Christian artists in our collection. We could see the intersection and reveal the sort of persistence of persecution of Jews and Muslims that we see in the world today. The same prejudice that showed up against Jews and Muslims in the Medieval world show up in today’s visual and architectural language.

We saw that in political language in the recent election, and we had an interfaith panel that brought the three faiths together to talk about antisemitism, where we see areas of overlap, and where we see areas of divergence during the period of crusades.

There are lots of opportunity to speak about open dialogue, communication, even in times in conflict in hopes of showing audiences that there’s more that unites us than divides us. So I think the Art of Three Faiths and people of the books know there are three different traditions that have had three different histories of majority/minority, oppression/conflict.

There is a lot of great borrowing and sharing and collaboration that happens within these faiths, which is the kind of healing I think we need in an art museum—but also in the world.” – Ben Simean, The Getty Museum

Upon entering the exhibition space, you are greeting with the words:

People of the Book/Am HaSefer/ ‘Ahl al-kitāb’.

That epitomizes the essence of this exhibition: a place for everyone told in pages of books that embody many throughout history.

Exhibition Now Through February 3, 2019

[columns_row width=”third”] [column] [/column]

[column]

[/column]

[column] [/column]

[column]

[/column]

[column] [/column]

[/columns_row]

[separator type=”thin”]

[title maintitle=”HONORING ALL BELIEFS” subtitle=”finding the beauty in difference.”]

[/column]

[/columns_row]

[separator type=”thin”]

[title maintitle=”HONORING ALL BELIEFS” subtitle=”finding the beauty in difference.”]

Art of Three Faiths takes the heart of the human species and our desire for storytelling, words of meaning, and honors three of the major faiths. With handmade pages, some with gold, the process behind these masterpieces is beyond enticing. For instance in the Qur’an manuscript, the way it is produced is remarkable. The scribe began in fish oil or fish glue and then applied gold leaf is hand painted onto the surface to affix the golf leaf to the bold, vocal symbols. It is beautiful and delicate and rarely seen.

“The sheer inventiveness of the artist over pages and pages and pages … I was overwhelmed by the numbers, the colors, it was fascinating.” – Elizabeth Morrison, The Getty

The Torah tells a larger story. Dating back to 1296, there are 1,000 pages and 150 significant pages of art. Estimating the Torah was completed on March 17th, 1296 because of a date written in the manuscript, the significance of this find is historic. While this manuscript has found a home in other museums and private collections, having these three manuscripts together represents a larger ideology that I hope everyone will embrace.

We need to find the human thread that binds us all. We’ve lost the respect for other faiths and cultures and we could learn as a species to not repeat the negativity.

“To hear the three languages recited or read in this space, you’d only really find that in a few places in the world. To think of the museum space of where we can have those sacred encounters is something we enjoy witnessing.” – Ben Simean

To learn more and stay current on the latest findings and studies, visit the Getty Museum blog, The Getty Iris. These blog posts bring out the narrative of so many substantial discoveries.

[separator type=”thin”] [columns_row width=”third”] [column]

EXHIBITION SUMMARY

These religions trace their belief in the singular God to a common patriarch, the figure of Abraham (Ibrahim). Practitioners of all three religions have been called people of the book for their shared belief in the primacy of the divine word as conveyed through sacred scripture. Copies of the Torah, Christian Bible, and Qur’an are among the most beautifully illuminated manuscripts of the Middle Ages, represented in this exhibition by three remarkable examples.

The Rothschild Pentateuch

Each page of the manuscript is divided into portions reserved for different aspects of its reading and comprehension. All of the texts are read from right to left.

At the center is the text of the Torah itself, written in a formal, square Hebrew script. It is accompanied by two sets of markings, one indicating the vowels (nikkud ) and the other specifying the way the text is to be chanted in ritual contexts (te’amin, cantillation symbols).

The inner margin is occupied by Targum Onkelos, the Aramaic translation of the Torah, with additional interpretation. In a tradition dating to the second century, when Aramaic was commonly spoken, the Torah was read aloud in both Hebrew and Aramaic.

The upper and lower margins contain themasorah magna, a commentary devoted to textual details such as the number of occurrences of individual words, which was was intended to preserve the accuracy of the text of the Torah over time. is commentary was written in micrography, minute Hebrew letters that o en formed elaborate shapes.

In the outer margin is commentary by Rashi, an acronym for Rabbi Shlomo Itzhaki (1040–1105). His commentary on the Torah as recorded in the Rothschild Pentateuch is one of the earliest dated copies of this text to survive.

At the bottom le is a catchword, a guide to assembling the parts of a manuscript (or book) in the correct order. Catchwords, which appear at the end of a group of pages, give the first word of the next group.

1 Comment