More Than Words…

Sebastian Junger | RISC | Restrepo | WHICH WAY IS THE FRONT LINE FROM HERE?

Sebastian Junger is a true journalist. A heartfelt documentary filmmaker. A compelling author. An insightful editor. A devoted friend and husband and above all – a man that believes in the decency of mankind.

Award-Winning Journalist & Best-Selling Author

Academy-Award Winning Writer | Director

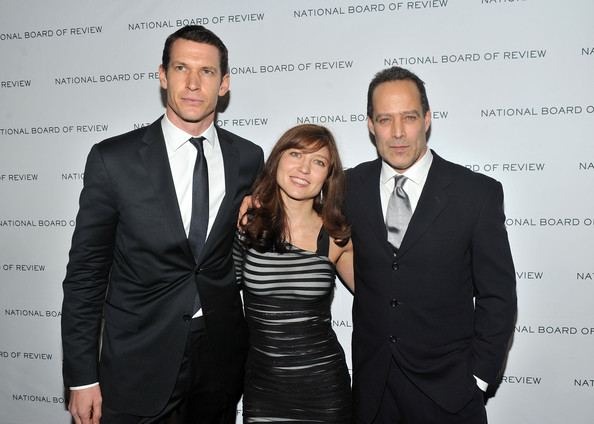

Let me start by saying that in another life, I would have been a field journalist covering human rights, war, civil unrest. Instead, I am only a disheartened observer who gets quite a lot of misinformation. I rely on journalism, as often as possible – unbiased news, thought provoking publications like the Economist, Newsweek (not since it ended it’s publishing in December), TIME, BBC, CNN, and on a rare occasion, Vanity Fair when I know Sebastian Junger has written a piece. I met Sebastian at the Academy Foundation of Motion Pictures, Arts, and Sciences in 2011. It was February 26th, the day before the Oscars. I also had the honor of meeting Tim Hetherington. Before meeting them though, I was introduced to their Oscar-Nominated film, RESTREPO. A film that captured the truth of war in an apolitical way. Just war. No politics, simply a group of soldiers sent to fight in the most dangerous parts of Afghanistan in the midst of a war few understood. Tim and Sebastian, sent on assignment by Vanity Fair, alternated their deployments into the region but each went for 5 months – spread out over the course of a year. Sometimes there together, sometimes on their own, they endured some of the more intense war situations that had been seen. It was the quiet. The eerie calm before mass gunfire that just permeated in the mountains of the Korengal Valley, known as the most deadly battleground in Afghanistan, especially during the peak of this uncertain war, the movie leaves you feeling the burden these soldiers face trying to return home once they’ve seen so much war, seen so much contradiction. It changed the way I saw war and although I am no fan of war, sometimes it is necessary. In this case though, the film opened up the door to exploring the psychology of war. That was where the impact really hit.

“My call to everyone: Every time you pick up a newspaper or see a documentary about war – remember those who risk their lives to tell you what’s happening. The quest to find peace and human justice is one that is heavy with sacrifice.” – DG, ATOD Magazine

That day when I met Tim and Sebastian, I became even more driven to tell a story worth telling. I became obligated (even moreso) to make the words I use have purpose. I’ll never forget listening to Sebastian and Tim when they spoke on the panel on stage that year. They were funny, deep, and utterly open. That sums up who they are in life. I was so grateful to have spoken to them afterwards. Sebastian and I stayed in touch and I remember the day I turned on the news and heard the news that Tim had been killed in Libya alongside fellow journalist, Chris Hondros. I cried. A lot. Tim Hetherington was the kind of guy that just didn’t hold back his pureness or strong belief that hope and humanity is worthy of the time and thoughtfulness it craves. In even the most horrific of his photography images, there is this underlying hope. I don’t know how he managed it but one can only assume in his heart, he believed good would inevitably clamor it’s way to the surface. His lens reflected precisely that. That day, I sent Sebastian an email and a few days later he replied. I know he was having a hard time mourning the loss of his dear friend. The entire world of photography, journalism, and those who knew the impact behind Tim’s life and body of work were all deeply sad. For a moment, the world stood still. You just don’t forget people like that.

While we stayed in touch, it wasn’t until I got the Radio Show that I felt I had the platform to really share some of the wonderful and important word Sebastian had been doing. I sent an email and, as he consistently does, he replied. I asked him if I could spend an entire hour interviewing him and he happily agreed. (This is just one example of how approachable and real he is.) The day came and on February 5th, I conducted the first part of our interview on my Radio Show, “A Taste of Dawn RADIO”. We talked for an entire hour delving into everything from the Arab Spring, Serbia, war, politics, elections, family, truth, hope, and touched on his assignments as a contributing Editor of Vanity Fair. It was an hour that opened my eyes, informed me, and awakened my political passions. We talked about Tim Hetherington, but above all the hour gave us all insight into why Sebastian is the journalist, writer, filmmaker, and man he is. He is uncompromising in coverage and is devoted to telling the story of individuals, government, and the often undefined lines between them both. After the Radio Show, I then asked if I could interview him for the Magazine. Once again, generous in time and spirit, he agreed.

I conducted the second part of our interview while Sebastian was driving into New York in the middle of a blizzard. The sounds of the windshield wipers smacking back and forth, screeching against the glass pane; the dog in the background silently riding along, and we spoke. And – in the midst of the interview my computer died and my microphone stopped working so I had to rely on my ability to do dictation – NOT an easy task. (My hat’s off to those who do only dictation!) So while I had one of the most important interviews in my own personal career, I have to say any conversation I’ve ever had with Sebastian has been one of utter admiration. I am certain I stumbled upon questions and he has always been gracious and patient and honestly, so easy going it makes writing about him something I can do with a relative bit of ease. So before I continue I want to thank him for always being so generous with his time and so willing to give me an opportunity to tell a different part of his story. As a woman who longs to be telling the story of the human condition, I feel beyond humbled that I have an opportunity to talk to Sebastian, who is, in every way just a guy who believes in humanity and who has the wonderful audacity to dare tell the story, good and bad, behind what that entails.

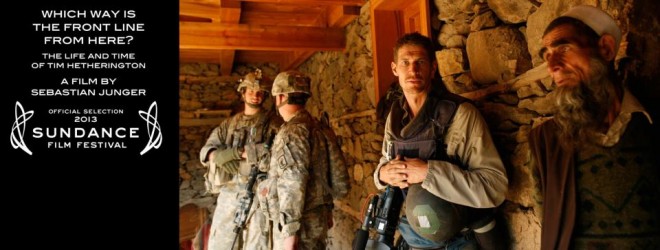

An accomplished Award-Winning Author of books that have been on the New York Best-Sellers List like The Perfect Storm, WAR, A Death in Belmont, FIRE; an Academy-Award Winning and Sundance Film Festival Grand Jury Prize Winner as a Documentary Filmmaker of Restrepo and Which Way is the Front Line from Here? The Life and Death of Tim Hetherington; the Founder of RISC: Reporters Instructed in Saving Colleagues. RISC was created after Tim was killed in Libya in 2011, Sebastian’s career and journey is one that is beyond important. Tim’s injuries could have been kept from being fatal had the journalists traveling with him knew how to treat the wound. That one moment – the lives lost were so valuable but Sebastian made a promise to not let it be in vain. He lost his dear friend Tim as well as fellow journalist, Chris Hondros. After that, RISC was born and under the training of the military versed in field trauma, men and women reporters going to the front lines or any assignment have the training they need to survive after attending RISC Training (Free thanks to the generosity of so many – DONATE HERE). Sebastian is unlike anyone I’ve ever met. He is brilliant, yes, but he’s real. No matter what he does or accomplishes, he never seems to lose sight of the importance of doing what he does. He values people, life, and true honest journalism. I have attached the video of the hour I spent talking to Sebastian as well as the interview we did on the phone at the close of this article. Listen to it. It will undoubtedly affect you.

Thank you again Sebastian for inspiring me to want to always be a responsible writer, to never be willing to compromise the quality of writing, and for being bold enough to remind so many of us that there is beautiful truth in words IF they are used with the utmost integrity. You continue to inspire me and I can’t wait to read your newest book! Below is our interview and just past that are links to some of the compelling articles Sebastian has written for Vanity Fair as well as links to RISC, his films, and how you can support journalists in the field.

ATOD – Dawn Garcia (DG): (On our phone interview)I read a piece you wrote in October of 2000 about the atrocities in Sierra Leone called, “Terror Recorded”. The scenes of being ushered into a dark doorway only to be locked inside and shown photographs, in great detail, of the slayings of civilians. When you saw those images, I can’t imagine there was a part of you that didn’t weep for what had happened. I once read a book called Season of Blood by Fergel Keane. The accounts of him, a photojournalist looking for survivors only to find literal pieces of human beings, mostly women and children, will haunt me always. I have been writing a story about that for 15 years. Not sure I’m quite ready for it all to come out. How do you manage the emotional repercussions of knowing the kind of hate that exists out there?

Sebastian Junger: I balanced it with the other truth, there is a lot of love and generosity and courage out there. Human beings are capable of tremendous good and tremendous compassion. I had a hard time. I don’t think it is hard coming back, I mean there are things you see when you’re there that you don’t forget but no, I think if anything, it restores my faith that there is enough good and (refer to above) to counter the bad.

(I tell him to try reading Season of Blood: A Rwandan Journey by Irish journalist, Fergal Keane. As we talk about the realities of war, he tells me about going there and learning about the people. Just throwing off everything and simply covering a story, meeting the locals, believing that mankind is certainly capable of doing awful things but in the end what remains is good and hope and that is far more important. He speaks with a conviction in his voice and I know that the successes he’s had haven’t swayed him from the meaning behind his writing, his work as a journalist, nor his passion for film. All of which stem around one very central theme: who we are as people.)

DG: What was the very first assignment you had on the front line – or in war?

SJ: First assignment was in Bosnia on my own accord during the civil war. I wanted to go. [Needed to] But the 1st actual assignment was in 1996. I was sent to Afghanistan.

DG: When you were growing up, were your ambitions always to write?

SJ: No, I mean when I was 10 I just wanted to live in a log cabin in Canada somewhere. I liked anthropology but didn’t really want to be an anthropologist. I didn’t know what I wanted to be. It wasn’t until I graduated college that I started to really figure it out.

DG: While being on assignment, was there a moment when you were given a meal that just allowed you to pause in all of the chaos? If so, what was it?

SJ: A meal that gave me a minute to pause [he goes silent for a minute to think about this]. I was brought up vegetarian. When I’ve been on assignment, you eat whatever they give. I’ve had to eat cow brains in Bosnia and goat heads in Afghanistan. At one point I remember them throwing a cow head on the table and just chopping it open with an ax. I’ve eaten some pretty horrific things!

DG: Having recently had your film selected as the 2013 Selection at the Sundance Film Festival, the movie is about your friend and colleague, Tim Hetherington. When did you first meet Tim?

SJ: I remember it well. First time on assignment on Vanity Fair met at a gate Heathrow on the way to Afghanistan. 2007. We immediately liked each other, got on and that was it. I saw his work as a photographer and I knew he was who I wanted for this assignment I was doing in Afghanistan. [Not having realized they had only known each other 4 years]. After we worked together on that, it was easy. We worked together whenever we could.

DG: When you spoke to me on the air, you told me about your injuries during Restrepo. What was the worst injury you’ve sustained while out in the field?

SJ: I was a climber for tree companies once upon a time and I hit my leg with a chainsaw. (He says nonchalantly)

DG: What was the first movie you ever saw?

SJ: National Velvet. 1965 – classic. I think I had crush on the woman in that movie – I can’t remember who it was right now [It was Elizabeth Taylor]. I mean, I was born in 1962 and that movie was from 1945 or s0mething. It was a classic.

DG: We all tend to gravitate towards music in some way at varying times in our

lives. What would you say are the 5 songs you know will provoke a memory – and

if you’re willing – what do they allow you to think of?

SJ: Reggae, Santana, The Doors, Jethro Tull, I don’t think there is a particular song per se.

(We talk about music and then I mention An American Prayer by Jim Morrison) Yeah, that’s a good one too.

DG: If you could go back in time , what would you want to see or study? Who would you want to meet? Political or otherwise A time in history?

SJ: Paleolithic early drawings – they are so intense and it’s incredible that they can still be seen on cave walls. Who would I want to meet. Well I’d have to say Saint Augustine. He was there at the beginning of democracy. He’s a prominent political figure but he was there when it all started. A time in history I’d have liked to have seen – the American Revolution. It was the birth of change in the Western world.

DG: We each have such different purposes as writers. If you could leave one truly infinite message within your work, what would you want that to be?

SJ: Don’t harm. I mean I’m an atheist, I’m in no way religious but if there is one commandment it’s do not harm.

DG: If you were to close your eyes and envision total serenity, where are you?

SJ: I don’t know. In the woods somewhere I suppose.

DG: What has been the most challenging aspect you face as a journalist?

SJ: (Without missing a beat.) Getting people to pay attention to things that affect them is an obvious one. I mean it’s hard to try and tell a story and get people to care about it. I think that’s probably the hardest part. [Empathy really is the most difficult thing to convey].

DG: I know you’re working on a new book, but I wanted to know, do you think it takes you less time to finish or more?[

SJ: They’re always impossible. Right now I don’t have a contract so I don’t have a deadline. (We pause a minute because the blizzard is getting more intense.)

DG: When you wrote the Perfect Storm, did you ever imagine it would be a film?[/question]

SJ: No, I didn’t care. I just never expected it to be such a big seller! [Perfect Storm was his 1st book followed by Death in Belmont.]

“[Re: Death in Belmont”] Junger’s book raises the possibility that Smith’s conviction was founded on circumstantial evidence, and in part on racism, because the prosecution’s narrative of Smith’s day in Belmont was built on witnesses who remembered seeing Smith chiefly because he was a black man walking in a white neighborhood. Smith had cleaned the victim’s house on the day in question and left a receipt (for his work) with his name on the victim’s kitchen counter. There was no physical evidence, such as bruises or blood, linking Smith to the crime. In 1976, he was granted commutation of his life sentence; however, before his release, Smith died of lung cancer.[26][27][28][29][30]

In his final analysis in A Death in Belmont, Junger draws no conclusions about the guilt or innocence of Smith or DeSalvo. The victim’s daughter has vigorously disputed Junger’s suggestion that Smith might have been innocent.[27] “

DG: Are you spending more time working on Vanity Fair? Are you still doing that on occasion?

SJ: The last piece I did was a while ago but yes, I will do something again.

DG: In a piece you wrote on Tim’s service, you said: “I missed most of that beautiful moment because I was crying too hard, but later I did savor one comforting thought: this may be one of the few countries in the world where a senator would see fit to present the national flag to a woman of Somali origin (Tim’s girlfriend) in honor of an Englishman killed in Libya. Whatever criticisms one might level at our county, we are sometimes capable of including the entire world in our embrace. In the midst of our painful debate about immigration, about war, and about our responsibility to other countries, it is an important thing to remember. It was perhaps one of the reasons that Tim had moved here—to escape what he felt to be the stultifying atmosphere of London.” Vanity Fair

– I don’t know that I’ve ever read a more impacting and conflicting piece of journalism. Something so polarizing and candid but also somehow comforting.

I feel like sometimes we see only the fractures within society, the brokenness of the world but in the shadows exists so much hope. In all of your field work, was there a moment in particular where you felt in spite of all of the horror, the war, the atrocity, you had a glimpse of pure hope?

SJ: [Sebastian pauses and tells me this story about how at Tim’s service, a flag was given to Tim’s girlfriend, Idil Ibrahim and the unity that was apparent during a service so fraught with sadness. When Sebastian talks about Tim, there is always so much emotion and love behind his voice. It’s near impossible not to see the two as synonymous in the world of journalism. Rather than go too deeply into it, I feel in this interview, it’s better to go with the words Sebastian himself wrote in a piece called, “The Hetherington Doctrine”.]

Powerful quotes: Here is the tough part, though: pro-democracy rhetoric is all well and good, but at the end of the day only actions count. No one will remember that President Obama supported the Arab Spring if it eventually fails and the region collapses back into the political Dark Ages. If we actively engage these movements with advice, with money, and, when necessary, with military force, then we get a vote in how it all turns out. Specifically in Libya, the idea that we are in a “third war” is patently absurd; with no American soldiers on the ground, our vulnerability is virtually nonexistent and the benefits are very real. Rebels are parading around with the American flag and openly praising our country—a far more convincing rebuttal of bin Laden’s rhetoric than anything the White House press office could ever offer.

About Tim’s work in a piece in The Guardian:

On the front line: a documentary tribute to Tim Hetherington

Sebastian Junger’s moving film about his war photographer friend, screened at Sundance, is also a call to action.

Three years ago, I had a beer at Sundance with the war documentarian Tim Hetherington. He was celebrating the grand jury award he had won for Restrepo, in which he covered a year in the life of US soldiers in Afghanistan. Last weekend, I sat in the same bar with his close friend and colleague Sebastian Junger, who was screening his new film about Hetherington’s life, and untimely death, aged 40.

The first part of the film’s title, Which Way is the Front Line From Here? The Life and Time of Tim Hetherington, is a line we hear Hetherington speak, in Misrata, Libya, on 20 April 2011, hours before pro-Gaddafi forces fired a mortar that struck and killed him, ending the career of one of the world’s most impactful visual artists. At the heart of Junger’s loving but unsentimental film is a tribute to Hetherington’s extraordinary work. He was not a traditional war photographer, nor documentary film-maker. He called himself an “image-maker” as that enabled him to work across visual media, from mobile phone downloads to multimedia installations.

Trained at Cardiff, he began his career in Liberia, documenting the impact of war on real people, and working as an investigator and teacher. In his photography, he depicted violent graffiti as the scars of war, and developed a longstanding fascination for how young men became enamoured with war. Always digging far beneath the surface, Hetherington was fascinated with how war created powerful bonds between men, and created an addictive normality of its own, making any return home a traumatic problem. This paradox was illustrated in his own life, as shown in his video project, Diary, intercut between his experiences on the front line, and his alienated time in England.

From his images of a Sri Lankan cemetery to those of Liberian footballers and sleeping American soldiers on the Afghan frontline, intimacy and engagement at the forefront of his worldview. He used a square-framed Hasselblad camera, which required him to look down, rather than directly at the subject. That let him see a different, more meditative dimension to the people and situations he memorialised.

Newspapers around the world, including this one, published his images, which often had historical value. He took the only shot that proved that Liberian rebel fighters used mortars to attack government forces in the capital, Monrovia. His impact was interpersonal too, as shown in footage of him negotiating with a Liberian rebel leader to save the life of a doctor suspected of being a government informant.

To deepen our insight into Hetherington, Junger shot candid interviews with those who knew him best. There is huge pathos in hearing his girlfriend, Somali-American filmmaker Idil Ibramim, talk of how she had been planning to start a family with the man she called “the Timinator”. Painful, too, was watching his stoical father, Alastair Hetherington, describe how he had had a premonition about his son going to Misrata, and begged him not to go.

“I had a very bad feeling, too,” Junger told me, “The only way to Misrata was by boat. Gaddafi had a navy, and didn’t want the press broadcasting his atrocities. I warned Tim that Gaddafi would start sinking boats. How are you going to get out, I asked him?”

Q&A: Sebastian Junger on Tim Hetherington

in The Colombia Journalism Review

“The ultimate truth about war is that you are guaranteed to lose your brothers.” – Sebastian Junger

“It’s not often that one sees characters from a film gather to mourn a filmmaker. On May 24, soldiers from Second Platoon of Battle Company of the 173rd Airborne Division joined friends, colleagues, and family of Tim Hetherington for a memorial service in a crowded church in lower Manhattan. Hetherington was an acclaimed war photographer and the co-director of the documentary Restrepo, which followed the men of Battle Company during their fifteen month deployment in Afghanistan’s Korengal Valley.

The film won the Grand Jury Prize at Sundance and was nominated for an Academy Award, and Hetherington and his co-director, the writer Sebastian Junger, took several of the soldiers along with them to walk down the red carpet at the Oscars. A little more than a month later, as civil war broke out in Libya, Hetherington lacked an assignment and decided to pay his own way to document the conflict. On April 20, he was photographing rebel fighters in Misrata, a city besieged by forces loyal to Muammar Qaddafi, when he was hit by shrapnel from a mortar round and bled out in the back of a pickup truck on his way to receive care. Another acclaimed war photographer, Chris Hondros, was killed by the same blast, as were several rebels.”

Please read the FULL STORY and take the time to watch Tim’s Video, “Sleeping Soldiers” that he made in Afghanistan during their filming of Restrepo documenting soldier’s sleeping and their waking dreams.