THE MAN BEHIND THE CAMERA:

AN ACADEMY TRIBUTE TO GABRIEL FIGUEROA

by Cord Montgomery

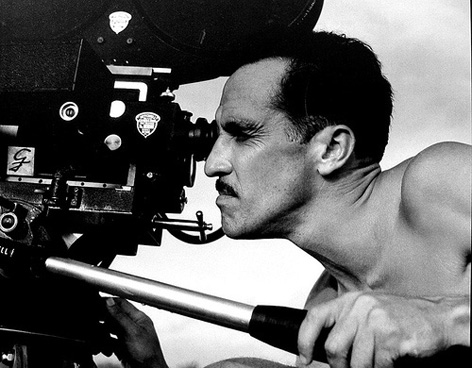

It is no secret that Los Angeles is a melting pot; it wouldn’t feel whole without the diverse cultures that help make it what it is. I try to think of filmmaking in similar terms: a film is also the sum of its parts, mainly the efforts of various crew members behind the scenes, often not receiving the recognition they deserve. Among those is the cinematographer, the person responsible for the images that capture imagination on film. Even though their role is crucial, he or she is often confined to the fine print on a lobby poster or a quick flash in the credits and yet, the work of Mexican cinematographer Gabriel Figueroa begs for attention. With a career spanning over five decades until his death in 1997, his profoundly emotional imagery made him one of the first cinematographers to have his name featured alongside stars and directors whom he collaborated with. The raw emotion he brushed across the silver screen with his camera captured feelings that dialogue often can’t reproduce–and people took notice. But today, many moviegoers probably haven’t even heard his name. The Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences is trying to change this. In addition to the exhibition at LACMA running from September 22-February 2, Under the Mexican Sky: Gabriel Figueroa–Art and Film– featuring paintings, photography, documents and restorations of rare films capturing his diverse and majestic career, you can experience this wonderment at your leisure.

Tonight is the prelude to the LACMA exhibition and tribute to cinematographer Gabriel Figueroa, a man who breathed life into classic American films like The Fugitive and The Night of the Iguana—but also endless amounts of Mexican classics directed by icons such as Luis Buñuel and Emilio Fernández, and as I walk inside the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences with my friend Michael, both of us in slacks and ties, a lush red carpet and the glimmer of life-sized Oscars welcome us. Wedged between the red and gold are the vibrant colors of floral shirts and dresses and a smiling, anticipatory audience speaking a combination of Spanish and English.

The gentle strumming of acoustic guitar sails across the room and decrescendos to dimming lights and applause as the President of the Academy Cheryl Boone Issacs welcomes everyone to a historic evening. Before delving into a panel discussion consisting of director/screenwriter Gregory Nava (Frida, El Norte), actor Gael Garcia Bernal (Amores Perros, Motorcyle Diaries), and cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto (Brokeback Mountain, Argo), she introduces a brief montage of Figueroa’s gorgeous, painterly cinematography that exhumes beauty even in the bleakest, desolate desert landscapes.

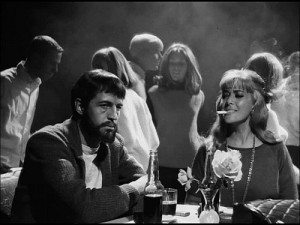

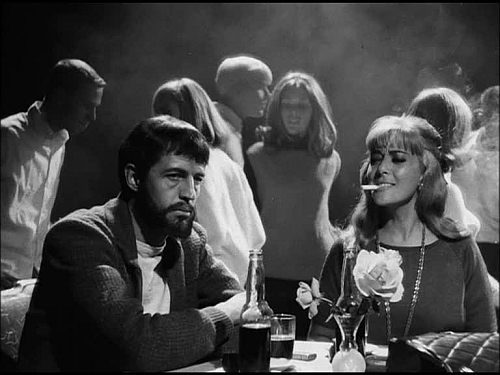

Red curtains recede as the montage comes to a close and Gregory Nava comes to the podium emphasizing how proud and humbled he is to host a tribute to the legendary Figueroa: the crowd agrees with applause. He explains how Figueroa is an extremely significant figure to the Hispanic population inside and outside of the United States, a group, despite its growing numbers, seems underrepresented in popular culture. The legendary cinematographer not only made a contribution to cinema, but he also defined what it is to be Mexican through his powerful imagery on film. Extended segments from La Perla, Victimas Del Pecado and Pueblerina serve as testament to the poetic expertise he had behind the camera, scenes including a woman’s troubled thoughts and misery depicted through a series of zigzagging, claustrophobic staircases and billowing smoke from a passing train—all shot across Mexico instead of on sound stages. Another scene portrays the uncertain future of a struggling family by a rainstorm looming on the horizon–an amazingly beautiful, calculated scene that, interestingly, was a spur of the moment decision by Figueroa and finished in a mere twenty minutes. There is a precision and thoughtfulness to each film displayed that is grippingly thematic and moody.

The curtain closes and Gael Garcia Bernal, Rodrigo Pietro and Gabriel Figueroa’s son, Gabriel Figueroa Flores, arrive on stage for a discussion about the wonderful cinematographer—but also the wonderfully interesting man. Not only did Figueroa have a profound influence upon cinematography and how it was regarded, but he also was a staunch activist against social injustice and injected political subversion into many of the films he worked on. These political undertones became a tradition and trademark of Mexican cinema, still carried to this day. As Gael Garcia Bernal cited in the panel, politics in Latin America are always on the surface, it is part of everyday life, unavoidable. Outside of filmmaking, Figueroa fought against corrupt film unions in Mexico, one conflict escalating to trenches being dug around studios and men armed with machine guns to help protect them from retaliatory violence from opposing unions.

Bernal mentions he is humbled to be even a small part of the night and the history—as is everyone onstage—mentioning that he owns an old smoking jacket of Gabriel Figueroa’s, still with notes and rolling papers in the pockets. It was given to him during a storm on a film shoot by a woman in wardrobe—coincidentally Figueroa’s daughter. It is an intriguing story on its own, but in other ways, because Bernal is a contemporary representation of the Latino presence in cinema, the jacket serves as an unexpected symbol of the legacy Figueroa passed on to generations of Latinos in the film industry. As more clips from Figueroa’s eclectic career are shown, it isn’t surprising why his work resonates with audiences so deeply. He has the ability to pry unexpected beauty from the direst situations using strategic close-ups of the tired, defeated eyes of a mother who has lost her child—while at the same time still being completely heartbreaking. It is this dichotomy of misery and beauty that penetrates many scenes. Yet he can also enchant with gorgeous settings such as two lovers paddling down a river covered in lily pads, the water rippling like a silk dress in a breeze, evoking raw sensuality that dialogue cannot match. With his masterful camerawork, Figueroa digs into unexplained depths of human experience.

The evening proved to have a series of surprise guests, the first of which is the strong, unflinching Mexican actress Silvia Pinal—featured in many of the clips shown, including Simon of the Desert in which she plays the devil. Pinal not only refused to go to Hollywood, but went on to become a powerful figure in Mexico outside of movies as a senator and proud crusader for women’s causes—even having her own statue erected in Mexico City. She takes the stage to a standing ovation and possesses an energy of someone wildly younger—she recently turned 82—and speaks through a translator, telling anecdotes and jokes about being pushed to eat worms and even breaking apart a cello for firewood in order to cook a sheep while filming. Also among the surprise guests, Michael Houston, a producer who worked with Figueroa that cites that legendary directors such as John Huston and John Ford went to Gabriel because they needed him in order to better capture their vision. Iconic Mexican-American actor Edward James Olmos appeared on stage last to say a few words, mostly about how profound of an effect Mexican cinema had on him as a child and how he thought an evening like this would never happen; and since Hispanics have such an astounding presence in the United States that it is about time this happened–and I agree. The panel discussion comes to a close as people exchange handshakes and hugs–Bernal quickly telling everyone to make sure to see the 1953 Luis Buñuel film El because of its understated brilliance.

The conclusion of the evening is a single scene from Enamorada, a scene that exhibits the unadulterated skill and artisanship of Figueroa’s eye. It is a scene absent of dialogue and in its final moments depicts a man on horseback riding toward battle. Alongside him, a brave woman marches gripping to the saddle, exchanging a proud look with the man as they forge forward into unforeseen circumstances and war. The imagery not only embodies the pride felt within the characters onscreen, but also captures the pride and spirit Figueroa poured into his career, an unwavering passion that Mexican cinema has carried from the past and will continue onward to the future.

In celebration of the new exhibition

“Under the Mexican Sky: Gabriel Figueroa – Art and Film”

Co-presented by the Academy and LACMA

Hosted by writer-director Gregory Nava (“El Norte,” “Selena”)

With special guests Gael García Bernal, Rodrigo Prieto, Gabriel Figueroa Flores and Silvia Pinal

Gabriel Figueroa is often referred to as “The Fourth Muralist” of Mexico, and his seminal cinematography contributed to the establishment of a visual culture and national identity in post-revolutionary Mexico.

The Academy’s tribute will feature stunning excerpts from many of Figueroa’s greatest cinematic achievements, as well as commentary from contemporary admirers such as actor Gael García Bernal and cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto, and from Figueroa’s son, Gabriel Figueroa Flores.

Clips from such Mexican classics as “María Candelaria,” starring Dolores Del Rio, and “Enamorada,” with María Félix, “La perla” and “Víctimas del pecado,” will be shown alongside Figueroa’s work for such diverse directors as John Ford (“The Fugitive”), Luis Buñuel (“Los olvidados”), Don Siegel (“Two Mules for Sister Sara”) and John Huston (“The Night of the Iguana”). Figueroa’s dazzling black-and-white cinematography for the latter film earned him an Academy Award nomination.

Figueroa’s contribution to the field of cinematography is truly global in scope, and his influence is still widely felt, inspiring DPs around the world to the highest artistic aspirations.