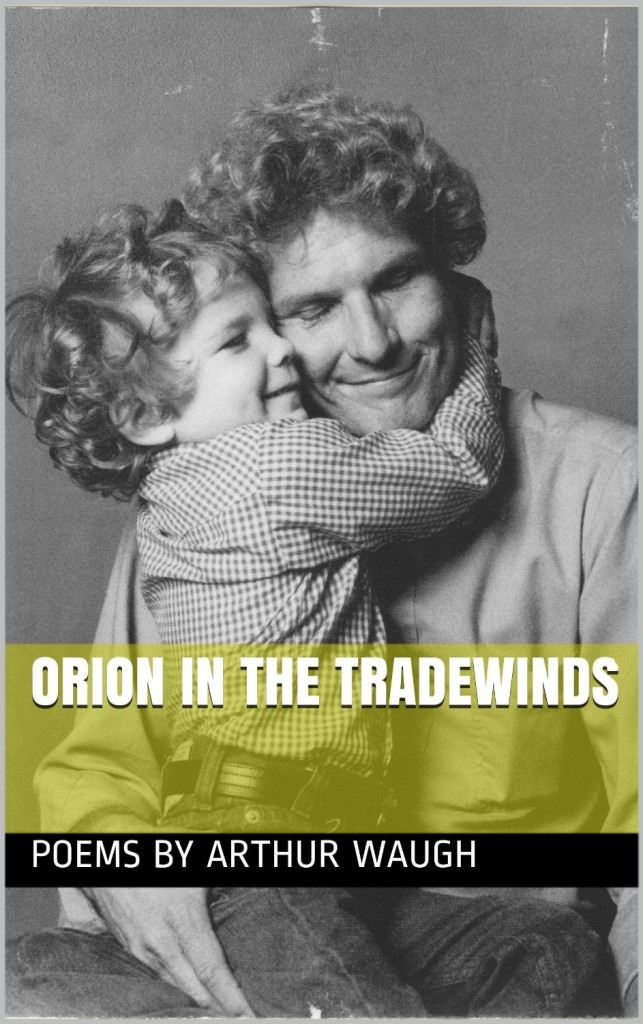

ORION IN THE TRADEWINDS

A Book of Poetry – Written by a Father, Given Life by His Son.

This is a glimpse into the book:

“Orion in the Tradewinds” by James & Arthur Waugh.

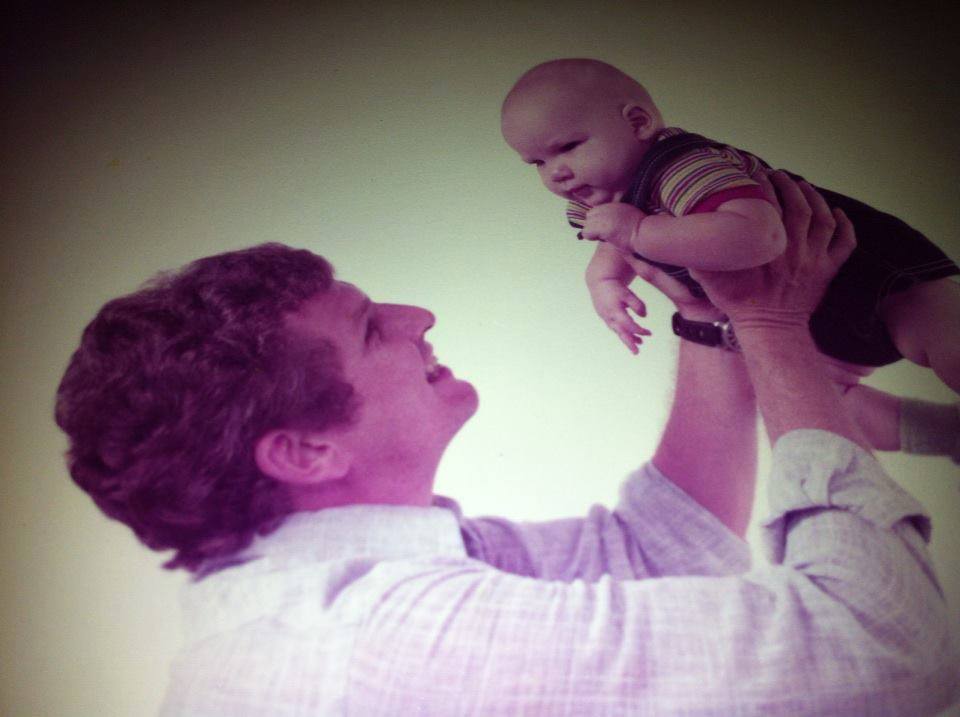

Arthur Waugh is a poet and documentarian whose works were found in literary journals in the 60s, 70s, and 80s. He is also my father. On May 18th 1988, on the cusp of having his first book of poetry published, this book, Orion in the Tradewinds, he suffered two massive cerebral hemorrhages leaving him with extensive brain damage, short term memory loss, terrible aphasia, and an inability to do the thing he loved most — write poetry. For years this manuscript has sat collecting dust, unpublished, used solely as my best window into the soul of the man I loved; a way for him to connect with me despite his handicap. Before his strokes, my father yearned to have this book published. Now, I’d like to make that wish come true. I’d like the world to get to know my father as I have, through his art.

Included in the book is a forward from famed English poet George Barker, who was my father’s friend and mentor in the craft, along with correspondence between the two. George knew how to describe my father’s work better than anyone else I have known and his quote below is an ideal description of what you are in for with this collection:

“Arthur Waugh is digging for a new moral vision in the dark or the stark verities of an abandoned Scottish coal mine. These dark or stark verities are the exact opposite of, say, Carl Sandburg’s loudmouthed sentimentalities: they seek to speak without lying about a world exclusively constructed of lies.” — George Barker, Poet

– James Waugh

I met James Waugh when exploring an opening for Story Editor at Blizzard Entertainment where James is Lead Writer, Franchise Development. We met, along with another writer, and in less than ten minutes we were already discussing the depth of story, the profound intricacies of character development, the beauty of humanity and how all of that translates into the realm of digital creativity. That said, James is not only an exceptional writer, he possesses truly exceptional qualities as a human being and part of that can be attributed to his parents. Recently, I found out about the book of poetry James’s father, Arthur Waugh has written, Orion in the Tradewinds. When James told me the story behind the book, I knew I had to help share it with the world. It is a book of poetry that is really, in its essence, a lifeline. It is romance, loss, passion, truth, devotion, change, adaptation, but above all it is the beautiful tale of a man whose heart is so big, words became the outlet. Having had the tragedy of his health, even then, somehow he still finds the beauty in everything – his entire being is wonderfully transparent.

Please enjoy a look into the life of a truly remarkable father and the love and support of his son … Writer to writer.

The book is $0.99 and proceeds go directly to Disabled Veterans of America.

Dawn Garcia – ATOD (DG): What was the first poetry your father introduced you to?

JAMES WAUGH (JW): I don’t really remember whether there was anything specific at a young age. We were a very eclectic family – my mother was a professor and had me reading the classics (Homer, Virgil, etc) at a very young age and my father was friends with a variety of writers like Ken Kesey and Shel Silverstein. I remember being surrounded by creative people as a child and our house was covered in books. I believe he gave me a copy of Howl by Allen Ginsberg, but I was already in high school then. I like the power of poetry, its ability to capture raw emotion and connect the dots of understanding for the un-definable experiences in our lives, but I’d hardly suggest that I’m a poet or even an avid reader of the art form. It’s more my father’s passion. I’ve been touched by it and I’m sure became a better creative and person because of that connection but I don’t remember being turned on to any particular poet in my youth that inspired me … aside from my father’s work.

In many ways, his work was really what I imprinted on the most. As a child whose father had aphasia and brain damage, it was hard to really get to know the man. He had his strokes when I was at the age of ten. Up until that time, we were thick as thieves. Not having him able to communicate as lucidly as he had was hard and his book became my window into who he was – it just happened to be a window that used poetry as its means of communication.

DG: If there was one word to sum up what this book means to you, what would it be?

JW: Gratitude.

I am grateful to be able to give this gift to him. Grateful to have friends and family who have picked it up and grateful to hear the joy in his voice, knowing his work has seen the daylight.

DG: What authors or poets influenced you growing up and, what authors and poets inspired your father?

JW: My father was very much a fan of William Carlos Williams, Byron, Derek Walcott, and of course George Barker, the poet who wrote the forward for his book. His work certainly shows flashes of William Carlos Williams and some of the beat voices of the 50s and 60s. His work is most definitely a product of its time, very much stimulated by the collage of change that was the 1960s, a war, and remaking himself in the 1980s. As Barker says in his introduction, his poetry is very Scottish. There’s a touch of a modern Bobby Burns – certainly inspiring him.

Otherwise, Hemingway was a huge influence. I’m a big F. Scott guy, he’s not. The Old Man in the Sea is his favorite novel.

DG: If you close your eyes, what childhood memory stays with you always?

JW: I have a very visceral memory of being in Miami International Airport with my father, going to pick my mother up as she returned from a conference. I was holding my father’s hand and walking amongst a forest of adults when I noticed an immense rumbling. Adults cheering, running, rushing to form a path. I had no idea what was going on. What could possibly make these adults work themselves into a frenzy. I remember my father looking down and saying something like: “You’re about to see a real hero.” He lifted me up onto his shoulders. I started to understand what the adults were chanting. It was “Ali, Ali, Ali” over and over and pretty soon Muhammad Ali was charging through the pathway with his security, holding up his hands and urging the adults to chant more. My father was drafted and joined the navy. He lost a lot of friends in Vietnam and hated the war, protesting against it. Ali’s defiance must have inspired him in his youth. But, the thing about the memory that strikes me the most is that even though we were merely feet away from the boxing legend, I can’t tell you much about what I saw. I was too busy with my arms wrapped around my dad’s neck and my face buried into his nest of blonde curls, so happy to be with him and be on his shoulders. As a boy, he was my real hero and to me much more interesting than the boxing legend.

DG: Favorite lesson your dad taught you that he will be proud to see you pass on to your children?

JW: There are a few. Kindness is a big one to me. My father saw a beautiful world that was too often cluttered with cruelty and believed it was incumbent upon each of us to be the counter weight to it. I learned to approach situations from a kind, understanding, point of view first. Conversely, he also gave me a strong sense of justice and righting wrongs. He taught be to stand up to fears and bullies. I remember clearly being in second grade and being bullied by a kid who would try to push me off of my bike after class. He finally did this once or twice and I think I came home crying. I was scared. He was bigger. He’d push me around in the halls. The school wasn’t really doing anything. This was during the time the Dominos pizza ads with the Noid were huge and I desperately wanted a pizza delivered to my doorstep on a Friday night in 30 minutes or less. Stick with me here … there’s a connection. My parents were ex-hippies and sugar cereals or fast food pizzas were not allowed. My father made me a pact. He told me that if I walked up to the bully and punched him, telling him that if he kept it up, I’d come for him every day, I’d get a pizza. It’s amazing the things children will do for a pizza. I remember going into school the next day and being mocked and made fun of by said bully. I remember feeling a flushing wave of anxiety and I remember more clearly my father saying that there are bullies in the world who will try to walk over you and that if you’re going to be a kind person then you’ll need to learn to stand up to them so they won’t. I also remember thinking of the Dominos ads and the pizzas looked amazing (who knew they actually weren’t). I ran up to the bully and punched him as hard as I could in his face. He crumpled to the ground and started to cry. His toadies didn’t really know what to do and scattered. It was very much like the scene from A Christmas Story. I remember yelling at the kid with my fist cocked back as he cried and held up his hand hoping I didn’t hit him again until finally, through his tears, he said he was sorry. I was never bullied in that school again. My mother was not pleased. Neither were my teachers. But I ate pizza that Friday night and learned that there are times you have to make a stand and that some people will only ever respond to that.

JW: There are a few. Kindness is a big one to me. My father saw a beautiful world that was too often cluttered with cruelty and believed it was incumbent upon each of us to be the counter weight to it. I learned to approach situations from a kind, understanding, point of view first. Conversely, he also gave me a strong sense of justice and righting wrongs. He taught be to stand up to fears and bullies. I remember clearly being in second grade and being bullied by a kid who would try to push me off of my bike after class. He finally did this once or twice and I think I came home crying. I was scared. He was bigger. He’d push me around in the halls. The school wasn’t really doing anything. This was during the time the Dominos pizza ads with the Noid were huge and I desperately wanted a pizza delivered to my doorstep on a Friday night in 30 minutes or less. Stick with me here … there’s a connection. My parents were ex-hippies and sugar cereals or fast food pizzas were not allowed. My father made me a pact. He told me that if I walked up to the bully and punched him, telling him that if he kept it up, I’d come for him every day, I’d get a pizza. It’s amazing the things children will do for a pizza. I remember going into school the next day and being mocked and made fun of by said bully. I remember feeling a flushing wave of anxiety and I remember more clearly my father saying that there are bullies in the world who will try to walk over you and that if you’re going to be a kind person then you’ll need to learn to stand up to them so they won’t. I also remember thinking of the Dominos ads and the pizzas looked amazing (who knew they actually weren’t). I ran up to the bully and punched him as hard as I could in his face. He crumpled to the ground and started to cry. His toadies didn’t really know what to do and scattered. It was very much like the scene from A Christmas Story. I remember yelling at the kid with my fist cocked back as he cried and held up his hand hoping I didn’t hit him again until finally, through his tears, he said he was sorry. I was never bullied in that school again. My mother was not pleased. Neither were my teachers. But I ate pizza that Friday night and learned that there are times you have to make a stand and that some people will only ever respond to that.

DG: What poem resonates most with your mom?

JW: My father is a true romantic. It’s almost embarrassing. He makes it hard for the rest of us guys. He still brings my mother a rose every week and grows them himself for her. Several of his poems are about or for her. The structure of his book is very interesting. The Distances chapter is very much about his youth and the 60s. Coming out of that era he was divorced and feeling immensely disillusioned with life in general and what his place was in it. The next section of the book, Lazarus, is his resurrection primarily due to meeting my mother and falling in love. From that point on his life, and the tone of the poetry, changes. You can feel the profound impact of his love for my mother on his life and the incredible sense of purpose and passion it gave him. Like Lazarus he was brought back from the dead. She’s acutely aware of this and I’m sure it would be very hard for her to narrow it down to a singular poem.

DG: In a world where everything is unexpected, what message do you most hope to convey with your father’s words?

JW: I’m not certain what I’m trying to convey, personally. If anything I’d like my dad’s work to find a readership, no matter how large or small and let his work convey whatever themes he intended. I’d like for people to know my father as I got to know him, through these poems and life perspectives. He was trying to make sense of the strange, rambling, nonsensical journey that is life as experienced through his emotions, perspectives, and era – a product of the 60s. I always believed it was a tragedy that his work, due to his strokes, never found a home. Poets are strange creatures blessed with a malady that few are, and their voices need to be heard. My father’s work is very earthy and not of the workshop school and fortunately today, the political and academic barriers of entry to publication can be circumvented through e-publishing. It gives me great pleasure to be able to make a dream of his come true. To see that dusty manuscript with it’s terrific introduction by George Barker be brought to the world, even if it’s only for friends, the family and a few curious readers. It makes me happy to hear how overjoyed he is that despite his handicap, his son able to help him see his book through all of these years later. All proceeds go to his favorite charity the Disabled Veterans of America, and it makes me happy to contribute to an organization that will put any money to important use. The book’s only $0.99. Check it out!

I want to give a warm thanks to James. Arthur is, much like his son, the exception in this world. To learn more, visit Orian in the Tradewinds.

To Sponsor an Article:

Follow ATOD Magazine™