So, where is the $8.5bn that South Africa was promised at COP26?

Written by Mark Swilling, Co-Director, Centre for Sustainability Transitions, Stellenbosch University

There is still no clarity about the nature, location, cost and management of these funds. One thing is for sure: No one really knows where they are exactly, what they can be used for, and when substantive negotiations will commence.

In November 2021 four Western governments plus the European Union (EU) announced at the COP26 meeting in Glasgow that $8.5-billion would be made available to accelerate South Africa’s energy transition.

The UK, US, French and German governments plus the EU formed the Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP) after a lightning visit of climate envoys shortly before the COP26 meeting. The World Bank’s Climate Investment Funds (CIF) facility has positioned itself as the de facto coordinator of the JETP.

The original $5-billion pledge was increased to $8.5-billion after the President insisted the amount be increased. Initial reactions by those associated with South African financial institutions were positive, mainly because it was assumed that this funding was either a grant or very cheap funding.

It is early March, and there is no clarity about the nature, location, cost and management of these funds. One thing is for sure, no one really knows where they are exactly, what they can be used for and when substantive negotiations will commence.

In the meantime, Eskom’s major lenders, the development finance institutions of these four Western countries, continue business-as-usual engagements with Eskom, including negotiating the terms of new loans to support Eskom’s projects.

President Cyril Ramaphosa has appointed former deputy Reserve Bank governor Daniel Mminele as the leader of a South African Task Team to lead the negotiations with the four Western governments and the EU that could result in a signed deal that will hopefully achieve the goal of supporting South Africa’s just transition.

There are two sets of issues that Mminele will have to deal with.

First, from the four Western governments and the EU, the exact nature of the funds on offer; specifically the cost of the debt and how much will be made available as grant funds or other catalytic instruments to support the just part of the energy transition.

Second, the pipeline of climate-related projects that South Africa would like to see funded.

As far as the nature of the funds is concerned, it is now clear that a small proportion will be grant funding — according to some reports, only about $500-million, with others claiming the figure could be as low as $30-million of the total pot. The rest, presumably, will be debt — supposedly at concessional rates (ie, at an interest rate lower than that which could be obtained on the market).

As far as the $500-million (or less) grant funding is concerned, it is assumed that this will be deployed to support the just part of the transition. This includes measures to mitigate the impact of job losses as a result of mine and power plant closures (including early retirement, relocation and/or retraining of workers).

It could also include measures that will create new opportunities, for example, training of workers for jobs in renewable energy and related sectors, or the repositioning of SMMEs currently dependent on the coal value-chain, or strategic industrial strategy work aimed at fostering upstream industrialisation to meet the demand of the new renewable energy economy (from making windmills, to green hydrogen).

The question is, of course, who will decide on the projects that this grant funding will support?

Global philanthropies might become participants, including the likes of the Rockefeller, Bezos, and Ikea foundations. What they fund will be informed by their thematic agenda and priorities. It is imperative that funding decisions take into account the views of trade unions, grassroots environmental groups and workers living in Mpumalanga. These funds should reinforce the capabilities of the poorest communities to create institutional capacities for determining and controlling their own development.

As far as the debt is concerned, the most pressing, and least-known factor is the cost of the debt. If the cost is higher than the cost of sovereign debt that the South African government can ordinarily raise on local and international markets, then it presents no clear advantages. Furthermore, sovereign debt raised in the normal way will have none of the climate-related conditionalities that will come with the $8.5-billion. Though the National Treasury will want Mminele to negotiate the lowest possible cost of debt, we can assume that the lower the cost the more onerous the conditionalities.

Furthermore, it is not clear whether the $8.5-billion is additional to what had already been earmarked for funding the South African energy transition. If it is a mere aggregation of pre-existing commitments that are taken to add up to the $8.5-billion commitment, then not much has been achieved.

A variation on this theme is that this is an aggregation of existing development finance commitments that have been repackaged as climate finance commitments. While it is true that climate-related investments can also have developmental impacts, this is not always necessarily the case. An unjust transition is decarbonisation that leaves poverty and inequality intact. Climate finance may catalyse decarbonisation, but not necessarily a just transition.

What about South Africa’s requirements? Assuming the $8.5-billion is real and can be made available on favourable terms (including an adequate level of grant funding), does South Africa have a clear framework and package of projects that can be funded over time that will deliver an authentic just transition? The answer is yes. The devil, however, is in the detail.

At the highest level of generality, we have South Africa’s Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) commitment tabled at COP26.

This commits South Africa to a carbon pathway of between 350 and 420 MtCO2e by 2030. The upper range is more or less within a gradual business-as-usual transition consistent with the 2019 Integrated Resource Plan (IRP) that includes investing in 2,500MW of new coal-fired power. The lower range is consistent with an accelerated transition, which includes faster-than-planned closure of power stations and mines, and the construction of around 6GW of new renewables every year for the next few decades. This means that the $8.5-billion deal needs to be judged according to whether it enables the lower-range pathway, or not. If not, it is not a worthwhile deal in climate terms.

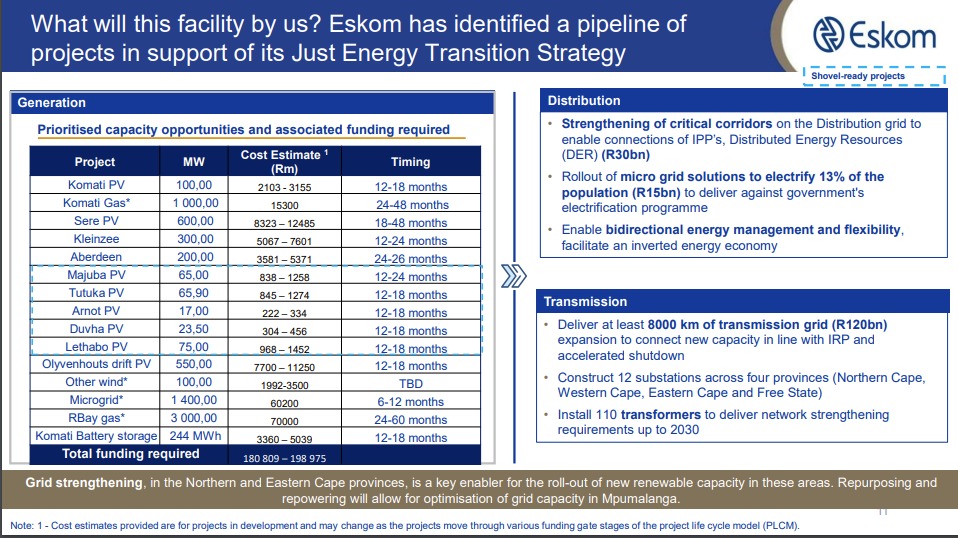

Eskom is, of course, going to take delivery of the bulk of the funds — with estimates ranging from 80% to 95%. Eskom’s challenge will be to present a pipeline of projects that are deemed by the funders to directly mitigate climate change. In presentations to the Presidential Climate Commission and elsewhere, Eskom has proposed the decommissioning of power plants in accordance with the IRP plan (which is, in reality, a catch-up action because the IRP deadlines have been missed) plus the earlier than planned decommissioning of Tutuka Power Station (which has also been the focus of serious corruption scandals).

Furthermore, Eskom has advanced plans for repowering and/or repurposing power stations that have been decommissioned. Funding for decommissioning, repurposing and repowering is clearly climate compatible.

Significantly, Eskom in recent months has been slightly shifting the narrative to include references to grid extension and transmission in light of the establishment of the new publicly owned transmission management entity. The grid is weakest in the southwest of the country where solar and wind resources are the strongest. It is strongest where coal-fired power generation is concentrated, ie, the northeast.

At the same time, 11 Renewable Energy Development Zones (REDZ) have been demarcated as priority zones for future investment in renewables. As our previous research shows, the REDZ located more towards the southwest can only come online for renewables if the grid has the capacity to evacuate the energy generated into the national grid. It is estimated that around R130-billion is needed for grid extension to enable a renewables take-off, with half of that available for execution in the near future.

The problem with grid extension is that funders might not accept that this directlymitigates climate change. Indeed, any improvement in the grid is good for all forms of power generation, not just renewables. Allocating a portion of the $8.5-billion to grid extension might raise questions in certain quarters. That would be a mistake — and it is heartening to see increasing attention on funding the enabling grid infrastructure needed in this part of the world.

Similarly, none of this funding can be allocated to improving the efficiency of power stations that are needed to keep the lights on for decades to come. Most of them contravene environmental regulations and require major investments if the Energy Availability Factor (EAF) is to rise from the present 62% to at least 72%, a performance requirement to re-establish energy security. Closing the most inefficient ones will contribute to achieving an overall improvement in the EAP, but still investing in the remaining power stations will be necessary (in particular to bring Medupi and Kusile up to the level expected for new power stations).

What South Africa needs from Eskom now is a clearly described pipeline of capital projects for at least the next two decades. The framework for this long-termist perspective is contained in the draft National Infrastructure Plan (NIP) 2050 that the Cabinet is set to approve in March. We need from Eskom a detailed pipeline that is compatible with climate finance and the NIP, but also the full detailed pipeline of projects (in particular grid projects) that need to be funded to ensure energy security, a necessary condition for a successful transition to a lower-carbon economy. This could build on the summary of the pipeline presented to the PCC.

Finally, a much clearer just transition programme is needed. The notion of a just transition is used in three ways:

- Mitigation of harm to affected workers and communities.

- Mitigation plus expanded opportunities via a massive renewables-led industrialisation programme (including green hydrogen, electric cars, etc).

- Fundamental structural transformation of the economy by transcending the capitalist mineral-energy-complex and creating a more just equitable society.

It is very clear that an intragovernmental political settlement that aligns the various ministers and the President around an ambitious transition to net zero will only happen if a convincing empirically realistic case is made that credibly demonstrates increased rather than reduced job opportunities for workers and poor communities.

Mitigation of harm is the minimalist programme many donors are focused on, but the political settlement will require the second option. Many trade unions and grassroots social movements emphasise the third, with the union Numsa — which first used the term “just transition” in the public narrative — insistent on this “eco-socialist” platform.

As the just part of the energy transition becomes the focus, donors, government departments, local governments, NGOs, researchers and development finance institutions are rushing to instigate projects in Mpumalanga.

But will this be about conventional top-down, donor-driven, development-as-usual practice, or will this be an opportunity for building bottom-up, community-controlled institutions that effectively deploy resources to make real-world impacts on the lives of affected workers and communities?

We cannot afford conventional NGO-based small-is-beautiful projects, given the need. Nor can we waste money repeating top-downism when the urgent and specific transition needs of communities (especially for women and youth) have been laid out so clearly by South African organisations for at least a decade. Instead, we need to replicate and scale what is already working — the Development Bank of Southern Africa’s (DBSA’s) D-Labs programme is a good example: developmental and entrepreneurial hubs that go to scale from day one, creating a platform for a vast multiplicity of grassroots initiatives to colocate within a well-resourced hub. They are being replicated in collaboration with the Presidency, government departments and municipalities.

Although Eskom spent two years crafting a framework for attracting climate finance, shortly before COP26 the government realised that funders were considering sovereign-level debt and therefore this could not be left to Eskom. As Eskom lost the initiative, the COP26 announcement made National Treasury realise that it faces a serious trilemma:

- Business-as-usual (ie, ignoring the global transition to net zero and the threat to SA’s exports due to its carbon intensity) will result in stranded assets that will ultimately land on the sovereign’s balance sheet.

- Taking on more debt to finance an over-indebted entity like Eskom adds fuel to the fire (especially if it is too expensive) because it could mean debt-financing the acceleration of stranded assets (which is why, maybe, the minister of finance has asked Eskom to try to sell them).

- The fiscal space for bailing out Eskom yet again to reduce its R392-billion debt is in reality non-existent.

The upshot is increased public debt and massive price hikes for electricity as load shedding gets worse so that Eskom can slowly move towards financial viability. The political consequences of this conundrum have yet to be felt. No matter how you look at it, the National Treasury is between a rock and a hard place. Will Mminele’s Task Team help it box clever to escape this very tight corner?

Finally, while the promise of the $8.5-billion has the virtue of focusing the minds of a country notorious for its attention deficit syndrome, it also, unfortunately, deflects attention away from the role of local funding. The Public Investment Corporation and the DBSA together hold a quarter of the Eskom debt and have not yet been invited to play a part in the solution. The same applies to local financial institutions (banks, pension funds, etc). With cash available for investing in infrastructure, will they come to the party if the enabling conditions are in place?

What role could the newly created Infrastructure Fund play? Created by the DBSA at the request of the President, this is South Africa’s first-ever large-scale so-called blended finance vehicle for blending public funds (with a high-risk appetite) with private funds (with a low-risk appetite) to finance massive public infrastructure projects. Does the Infrastructure Fund have a role to play in blending local and international public and private funding to enable the acceleration of the energy transition? What is certain, is that if the $8.5-billion does not mobilise local public and private investors, its impact will be negligible at best.

Given these complexities, Daniel Mminele’s Task Team faces a tremendous challenge. The President needs to be commended for making this pre-emptive appointment now because it comes at a time when the international funders are in disarray. This is a good thing for South Africa because it means that there is a small window of opportunity for the South African government (including Eskom in pole position) to set the agenda, rather than wait for this to be firmed up by global players.

To negotiate with a clear position on what South Africa needs (ie, the pipeline of projects) and on what terms (cost of capital, amount of grant funding for the just transition) is possible for now. And if this is done in a way that foregrounds the role of local public and private investors, then we may have a chance of turning the COP26 promise into a reality that works for South Africa and our own home-grown just transition.

This article by Mark Swilling at Daily Maverick is published here as part of the global journalism collaboration Covering Climate Now.