Grace Nkem explores the cultural influence of the digital world and the reflection of self through her art

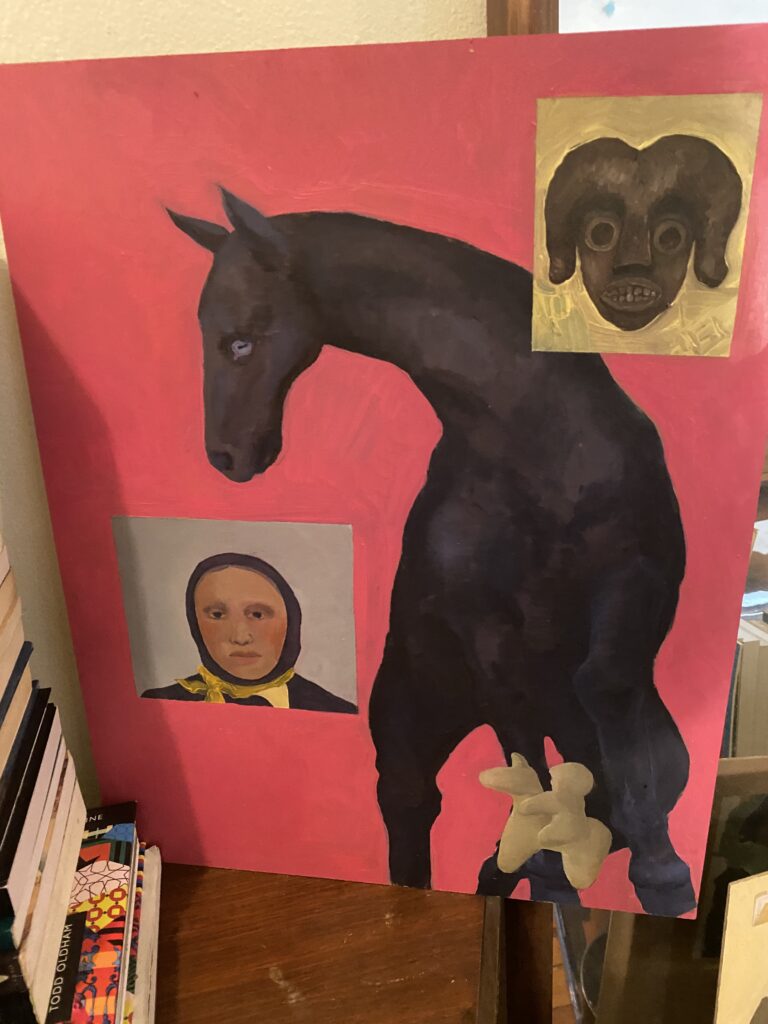

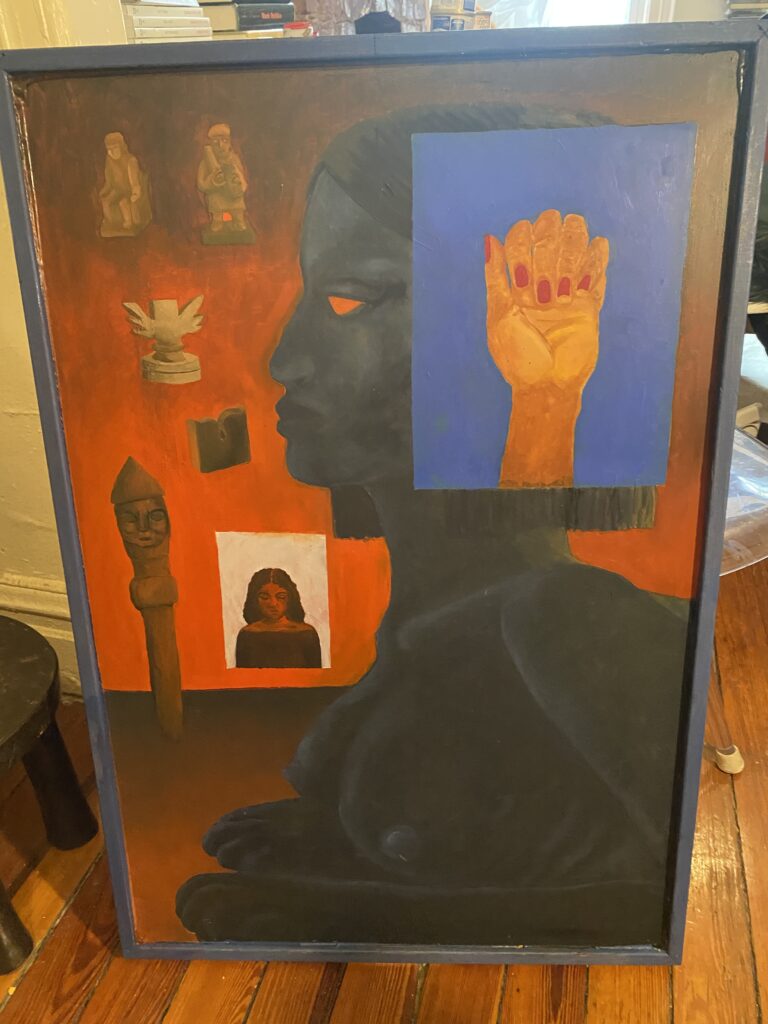

Grace Nkem is a Nigerian Russian surrealist artist born in Russia now living in New York City who, after recently graduating from Columbia University, is already an artist in demand. With several exhibitions throughout New York, Nkem’s works showcase a feeling of isolation impacted by technology, a warmth of femininity with the fierce hand of power, the insistent themes of irregularity, and polarizing truths and mistruths—all of which require a suggested patience that begs you to look closer.

When you listen to her speak about art, it’s as if her soul has lived a thousand lives and it is evidenced in the pieces she creates. Her depth is that of an ocean—endless and wholly unexplored—and yet, you know there is magic and wisdom abounding that can only be unlocked over time and creative exploration. Recently back from visiting Art Basel, we spoke with Nkem about art, her process, and the richness that exudes in her work.

This description: In her work she grapples with the ills of social alienation, mass digitization, and globalism, ironically noting that she owes her very existence to the latter of the three.

-

- What moment in your own life really polarized the clarity of these rather enormous societal issues that seem to affix themselves to us – even without our permission?

- How do you embrace the intersection of all three?

I cannot pinpoint a single moment, it’s been more of a continuous mounting awareness.

I studied art history in college, but over time became increasingly interested in political and social theory and criticism. I cannot overstate the impact Walter Benjamin, Guy Debord, Jean Baudrillard, and Mark Fisher have had on me.

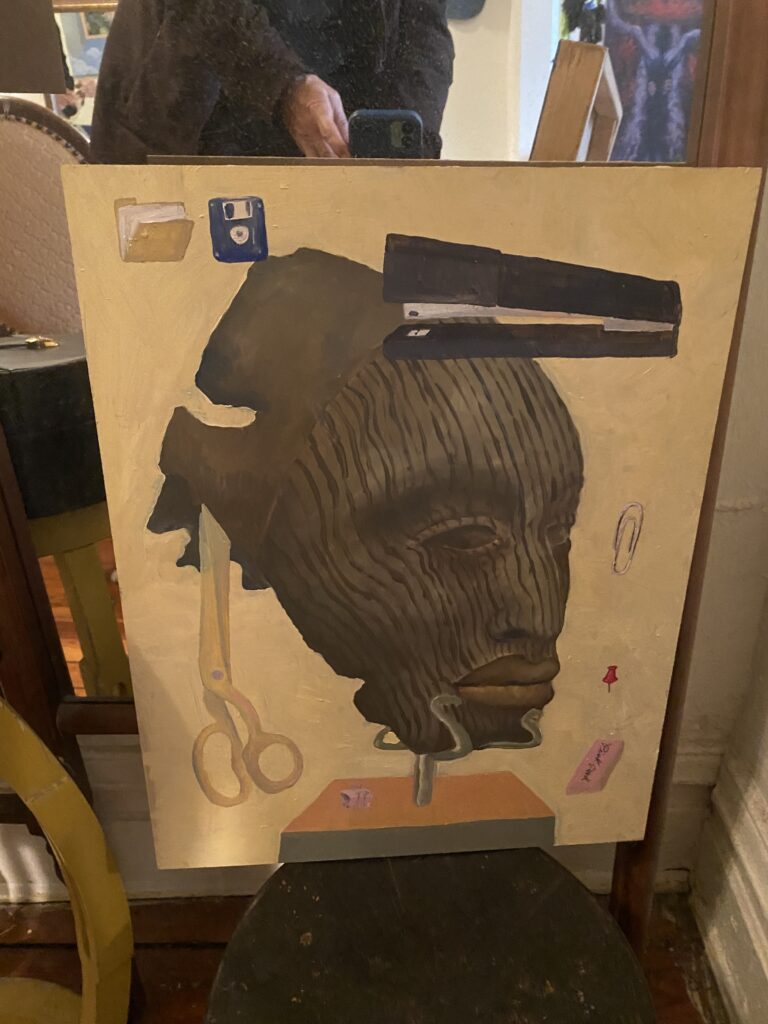

It is with them in mind that I identify the screen as the intersection of social alienation, mass digitization, and globalism. The digital screen is a completely phantasmagoric image, a place where all images exist at once. It is a mirror. And it’s completely changed how we view the world around us.

A lot of the motifs in my work come from screens. Floating images (icons— or should I say apps?), image overlays (browser windows), and the rolling green hills beneath a blue sky (the iconic, default computer wallpaper of Microsoft’s Windows XP operating system).

Digital reality has completely superseded physical reality. Even our currency and daily transactions are digital.

I often imagine how far back the space between the surface of my computer screen and the desktop wallpaper goes. In reality there is no space there. But I still like to think it’s about as shallow as an analytical cubist painting.

Young, old, novice or legendary, artists have been giving away bits of their souls to those willing to see it, since the beginning of time. What part of your own humanity do you expose?

I think I am constantly revealing my own attachment and devotion to a small piece of art history: Western painting. On the one hand, it’s obvious: I’m an art historian and a painter. But I am slightly embarrassed to admit that my subject-matter is more diverse than my influences. Perhaps what I’m revealing is a hidden love for tradition.

As a student of art, you’ve taken in countless works through study, but there are so many controversial pieces that must have really awakened something inside of you. Is there a theme you found that scared you enough to run towards it?

The spectre of terrorism. It seems untouchable, which makes it all the more tempting. I am conflicted by my own use of the imagery. Two out of a series of three pieces on the theme are sitting in my studio only half finished. But I think I’ll return to them soon.

With the public and institutional recognition you’re receiving, how are you meeting the growing interest in your work?

By spending a lot of time in the studio! That’s really all you can do. Seeing people respond well to my work is great motivation to make more.

You tell a story about your fascination of the Moretta mask. It’s significance for women as a vow of silence is something that seems rather poignant for the modern world. Why is this symbolism intriguing to you?

The silent, servile woman behind a mask is almost too good a metaphor. It speaks for itself.

But, it also has a bit of duality. Beyond the vow of silence, the Moretta also gives the wearer the glamor of anonymity. Ironically, it works just like an oversized pair of sunglasses— it gives the wearer a pass to look but prevents the wearer from being looked at. I could see Mary Kate Olsen running around in a Moretta during the iconic NYU era.

“I can see you but you can’t see me— and I certainly will not speak.”

Did you ever struggle with the cultural juxtapositions of your heritage, or did it liberate you as an artist to explore the many facets of who we are as people?

My heritage definitely informs my work but not at all in a sense of struggle. It just means that I have two wells in which to drop my bucket. And I think it helps me make sure that my artwork— the small bit of our collective cultural narrative that I can tell— dissolves preconceptions and helps to expand the notion of what a “normal” human identity looks like. Everyone is always surprised to hear about my background but it feels so regular to me!

Lastly, what does passion mean to you?

It’s life-giving and life-affirming. A generative force. Something that can help fill Pascal’s infamous God-shaped hole.

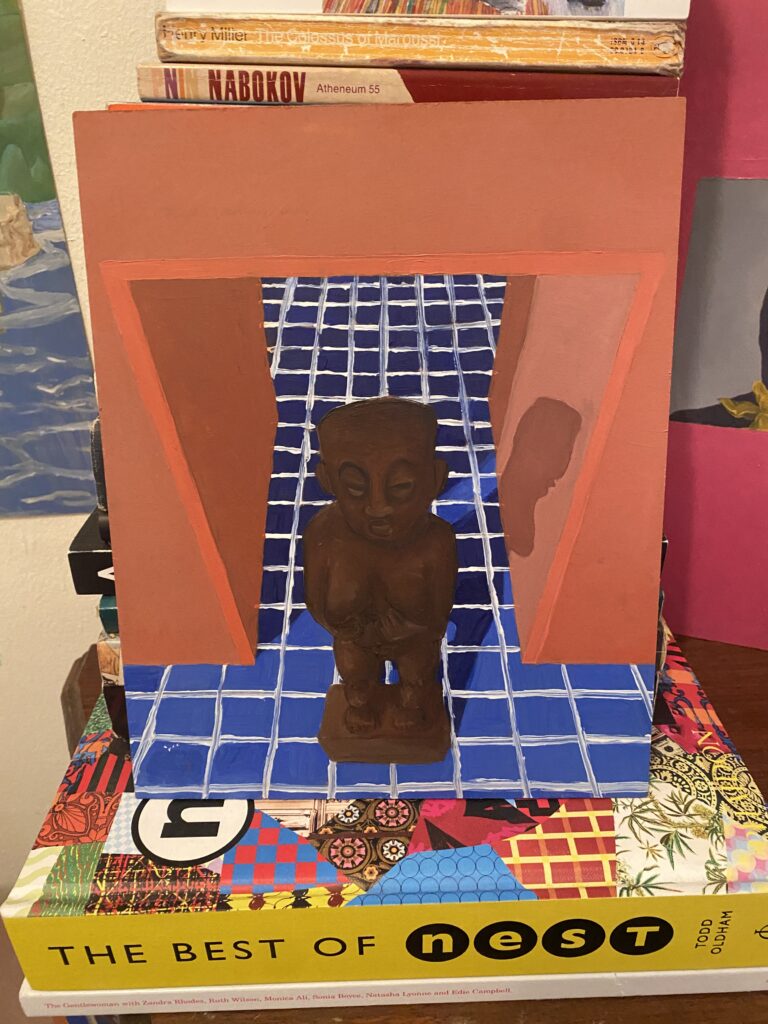

Gallery Particulier is thrilled to announce the upcoming solo exhibition of emerging artist Grace Nkem. Emphatically a painter, she explores and assembles images, which have multiplied exponentially in our modern world. The exhibition Images Will Talk will gather some of her recent works with their flamboyant palette and daring compositions. In addition to her gallery work, Nkem also works within the community to bring art to local high schools.

Opening Dec. 7, 5:30-7:30 pm

281 Maple St, Brooklyn, NY 11225

Exhibition Dec. 7, 2002 – Jan. 23, 2023

By appointment

Artist Bio

Grace Nkem is a Nigerian-Russian painter from Tver who studied Art History at Columbia University and now lives and works in New York City. In her work she grapples with the ills of social alienation, mass digitization, and globalism, ironically noting that she owes her very existence to the latter of the three.

Formally her paintings are inspired by twentieth century figurative painting, twenty-first century digital painting, and the internet writ large, where, in the artist’s own words, “all images seem to exist at once.” Leaning heavily into luminous, contrasting color palettes and crisp atmospheres, Nkem brings together disparate images through free association, noting that it takes very little prompting for the human eye to dive into metaphor; when objects are put beside one another in a picture, a connection inevitably arises between them. Meaning in her work is therefore produced according to both the internal logic of her paintings’ visual language and the social context they are viewed in.

Nkem is unabashedly open about her deep interest in late twentieth and twenty first century cultural critics like Ta’Neshi Coates, Mark Fischer, Hito Styerl, Nick Land, and Jean Baudrillard. Nonetheless, rather than produce commentary her work asks viewers to tease issues out for themselves.

Nkem is unabashedly open about her deep interest in late twentieth and twenty first century cultural critics like Ta’Neshi Coates, Mark Fischer, Hito Styerl, Nick Land, and Jean Baudrillard. Nonetheless, rather than produce commentary her work asks viewers to tease issues out for themselves.

Nkem’s main goal is to produce artwork that rewards sustained attention as she works through themes that weigh heavily upon the modern psyche: mass hysteria, truth and untruth, racial antagonism, class consciousness, the dissolution of consensus reality, the spectre of terrorism, compounding loss of cultural history, rampant wealth inequality, the tyranny of the digital, and a cultural preoccupation with perceived social decay.

1 Comment