UB40: A Band of Brothers

Interview by Greg Barraza

Official Site | Facebook | Twitter | Instagram

The story of UB40, and how this group of young friends from Birmingham transcended their working-class origins to become the world’s most successful reggae band is not the stuff of fairytales as might be imagined. The group has led a charmed life in many respects, it’s true, but it’s been a long haul since the days they’d meet up in the bars and clubs around Moseley, and some of them had to scrape by on less than £8 a week unemployment benefit. The choice was simple if you’d left school early. You could either work in one of the local factories, like Robin Campbell did, or scuffle along aimlessly whilst waiting for something else to happen.

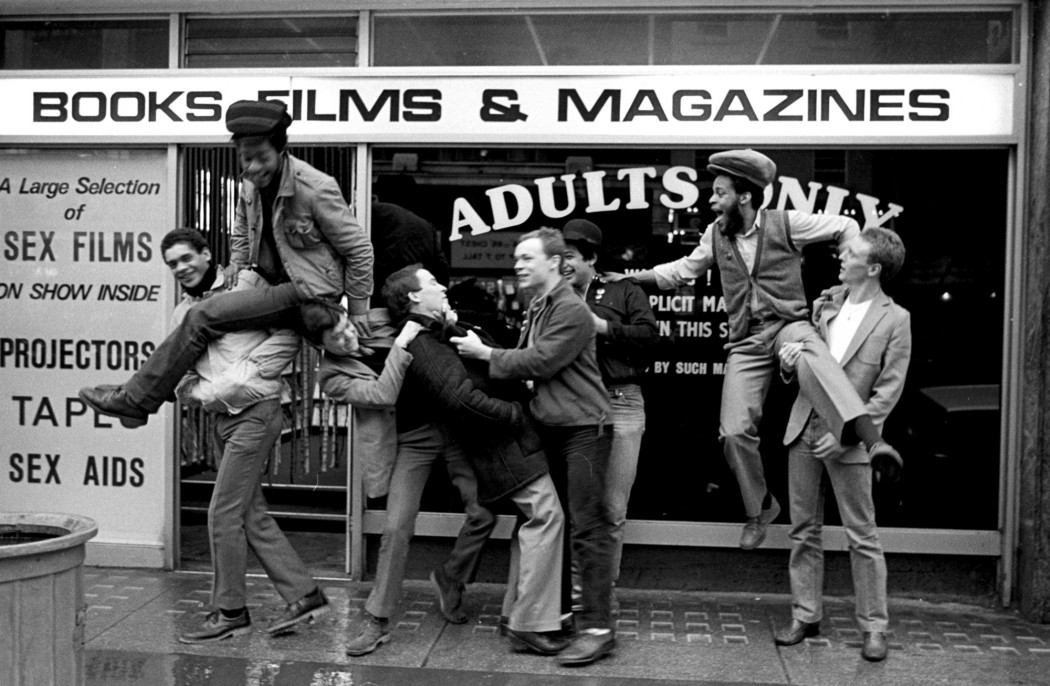

By the summer of 1978, something else did happen, and the nucleus of UB40 began rehearsing in a local basement. Robin’s younger brother Ali, Earl Falconer, Brian Travers and James Brown all knew each other from Moseley School of Art, whilst Norman Hassan had been a friend of Ali’s since school. Initially, they thought of themselves as a “jazz-dub-reggae” band, but by the time Robin was persuaded to join and they’d recruited Michael Virtue and Astro – who’d learnt his craft with Birmingham sound-system Duke Alloy – the group had already aligned themselves to left-wing political ideals and forged their own identity, separate from the many punk and Two Tone outfits around at that time. The group had nailed their colors to the mast by naming themselves after an unemployment benefit form. Their political convictions hadn’t been gleaned secondhand either, but cemented in place whilst attending marches protesting against the National Front, or rallies organized by Rock Against Racism (UB40.co.uk).

So when I received a call asking if I can be at a Los Angeles hotel in an hour, I said, “Sure.” I knew I would never make it to L.A. from Santa Ana in an hour, but I did not want to blow the opportunity to interview one of my favorite bands. On the way, I gave my friend’s, David and Todd, a call, “Hey guys. How does your schedule look?”

“Not too busy. What’s up?”

“Well, I just got off the phone with Roberto, and we have an interview with UB40 in about 45 minutes. Do you think you can get a crew together to shoot it?”

“Todd and I can be the crew.”

“Rad! See you there!”

So I stepped on the gas, and my car sped to a grinding halt in the pre-L.A. traffic; I think I topped out at around 30 mph. Needless to say, I was pissed. I needed to be in L.A.! So with the skill of a db (douche bag), I started weaving in and out of traffic, driving on the shoulder, faking I was getting off the freeway then getting back on at the last minute. I made to the hotel in 55 minutes, just as Dave and Todd were unloading the camera equipment. I ran up to the second floor banquet room where the boys from UB40 were just getting off the elevator; it was one of the first times in my life I was speechless. I think Roberto noticed this, so he introduced me to the band. We went over some minor items about the interview and were told by the road manager, “Alright mates. You got an hour because we need to get on the road.” About two and half hours later, we finished the interview. That is a great example of the great people UB40 are. They are completely unselfish, constantly concerned that we were getting what we wanted from the interview. When the interview was done, the last question they asked was, “Did you get what you wanted?” I answer, “Yes. Thank you.” They laughed and said they should be thanking us. At that moment the road manager came to us and said, “We really got to go.” And we parted. Roberto and I talked for a minute, then I drove home slowly (on purpose this time), smiling because as a 10 year old boy listening to UB40 on KROQ, I never thought I would ever interview them. Here is a very candid and cognitive insight to one of the greatest reggae bands ever.

ATOD – Greg Barraza (GB): Jimmy you have been described as a talkative anarchist and an outspoken commentator on social and political matters why is this so and what makes you so fired up? (The perfect example of this will be exemplified later in the interview; the third to last question to be exact)[/question]

UB40: I don’t really know. As long as I can remember, I have always had an affinity to the underdog and don’t like to see people taken advantage of and that works politically as well. When it comes to the anarchist thing. Yeah I’m not one for rules.

GB: So can reggae be categorized as protest music, speaking of war, poverty, discrimination, oppression, and politics?

UB40: It can be all those things. It is quite versatile in music. It can be for lovers. It can be for fun and it can be political. It has the gravitas to carry politics as a subject which Marley proved. It just shows how versatile the music is. It can do all these different things. Make you think make you dance; make you feel nice. That is all part of reggae.

GB: Jimmy Cliff, one of the forefathers of ska and reggae music, his perception of reggae is the cry of the people; the cry for recognition for identity, respect, love, and justice. Do you tend to agree?

UB40: (hesitantly) Well ok. There is a problem with that. You know just like the English language is no longer for the English; it’s an international thing. Reggae is an international language and whatever it meant to Jimmy Cliff, it is probably different than what it means to me because we come from completely different environments. I’m sure this is where reggae started, and it is the voice for the people. It was not made by middle class people or the establishment. It was made by poor people. So yeah, it is the voice of the people, but it is more than that now because it has become an international language.

GB: Earl, how do you feel taking on lead vocals being a bassist; I know it is difficult for a bass player to hold down the rhythm and also sing. I notice you often take the mic front and center and someone else plays bass. You perform on songs like “Baby” and “Reggae Music”; was this a voluntary thing or did the band ask you to come front and center?

UB40: I was kind of gently bullied into it (laugh) over the years, but I do actually enjoy it. It makes a difference than standing there playing bass. It breaks up the set for me also. I do really enjoy it but I can’t play and sing at the same time, so Jimmy usually triggers the bass line, so that frees me up so I can go out front and do my thing.

GB: There is a phrase that stands out in a song called “Reggae Music” where you say, “friendship comes first and the band comes second.” Can you elaborate on the strength of this strong bond UB40 possesses?

UB40: Like I say in the song because it is about our friendship because we all went to school together. We all kind of met when we were 11 years old going to secondary school, but I did kind of know Jimmy before that because he is from the same district, you know. He went to school with some of my friends. And we got that bond because we were friends before the band was in anybody’s mind’s eye. So we got that strength. We always used to hang around together, like me and Brian were good mates. And Ali obviously and Duncan went to the same school; he was in the same year as Jimmy. So it is a proper family thing, yeah.

GB: It is a family and the heavy influence of dub producer techniques by your brother Ray Pablo Falconer crafted the UB40 sound in the studio and live in concert. How did the two of you shape up the early UB40 sound?

UB40: The dub thing that we used to do on the tracks we all used to partake, actually physically get on the desk; one on the reverb, one on the echo, etc. Then Ray would translate that live. There was literally like 8 hands on the desk. It would take a long time to work out because he was like we have to do it live. We used to do a few edits after but basically it was like live mixing. It was really great fun we all loved it.

GB: I’m telling you it was like any other reggae out there because every night was a different experience. How is reggae music different than any other types of music when it is performed live?

UB40: (deep thought) it just got a power to it, you know. It’s hard to explain. I can’t remember who said it, but he said word, sand, and power. That’s what reggae music is if you are doing it right. Like jimmy said, it can convey love, dance hall, a little bit of fun. And like serious stuff like Bob Marley. I actually went to see him before I could play an instrument, and it kind of like inspired me to join a band and whatever.

GB: Jimmy, you mentioned that playing in a band for 30 years has been your lifeline. You strive to perform better each and every night. What are your checks and balances on and off stage?

UB40: Umm. (long pause…thinking) I really don’t think there are any checks and balances because in the end it’s either right or it isn’t. You want it to be perfect every night. You want it to be exactly perfect every night and you never do. There’s always some little thing that goes wrong, some little thing. But you’re always wanting to get it perfect. And the thing about reggae is that you don’t do much so what you do has to be perfect because you’re not riffing. You’re doing one or two simple things but those simple things need to be done perfect or else they won’t even work.

GB: Let’s talk about dub music and how it differs from reggae. What is dub music? Raw rhythm? Explosion of sound? Bass and beat?

UB40: To me dub music is…well…the history of it…we are talking the very early 1970s in Jamaica. And they would release records with a song on one side and an instrumental on the other side so the DJ can rap over it. What eventually happened was producers who wanted to make a name would start to mess around with the instrumental track, create some atmosphere. Take away their top line and create space and use effects for atmosphere, and that was how dub was born. Then, you had people like Lee Perry and King Tubby and Prince Jammy and they took it into an art form really. In the end it’s musical space. You take away things and let the bass line lead things and create space. That’s the melody for the whole tune. You give it space, follow the bass and you got the tune. Which is a really difficult thing to explain but a nice thing to listen to.

GB: Let’s talk about sampling. Did sampling come as a result of dubbing?

UB40: The thing about the use of electronics is in reggae, they took it on really quick because you could use computers and you didn’t have to feed a computer, so it was a lot cheaper to have a computer and a rapper than having a full 7 or 8 piece band. I think reggae did adopt technology quite quickly out of necessity really, but when it comes to sampling, yeah you know, we use samples live but we don’t use backing tracks. You’re still reproducing these sounds live but you can steal a sound from another record if you want to, you know like a wind chime sound or an echo. There are sounds you may want to use. Sampling makes things a lot more fun.

GB: Sly [Dunbar] and Robbie [Shakespeare] are the premier rhythm section in Jamaica and they produce Ini Kamoze back in the day.

UB40: Brilliant, brilliant recording.

GB: And now a lot of young people heard of Ini Kamoze as a result of the dub and the sampling of the Damian Marley. Can you go ahead and tell us how reggae is recycled often and updated?

UB40: Yeah. It gets updated all the time. I mean you got all the Studio One [famous Jamaican record label] bass lines and they always get rehashed; they call that classic rhythm tracks. They always get rehashed. They always get updated because you got new styles like dancehall. It’s like a little arsenal of classic music that will get used like Damian Marley using it as a backing track because it is just a brilliant backing track you know what I mean. They didn’t have to do anything to it. They just brought it back as an original track, and it’s still firing which is a beautiful thing.

GB: And how UB40 has been respected among the reggae fraternity by having super producers like Sly and Robbie work hand in hand with you on various projects. Can you elaborate on how reggae has been conducive to bringing people together who otherwise may have never met?

UB40: There is this thing about—we had it back in the day—because we weren’t all black and we weren’t all from Jamaica that you can’t play reggae, but the reggae fraternity itself they are not like that they are into peace and love. The boys have always shown love to us. All the artist we met over the years, which is basically everybody you know what I mean, have just shown pure love for us. Lots of people who come to us, like we got this gentleman from Germany, he’s like a massive reggae singer lived in Jamaica sounds like an authentic reggae artist and he’s like German. You know that guy from Bermuda.

GB: Collie Buddz.

UB40: Collie Buddz. We played with him on a big show in his home country. It is just pure love man. It’s just journalists try to make something out of what it is not. You can’t play because we don’t got the right genes; we don’t really check for that, and you don’t get it inside the actual reggae fraternity itself. They embrace it; they love the people that try to make the music that comes from Jamaica.

GB: On your Labour of Love Volumes I-IV you often bring artists who have been thrown in the back seat and have never seen the limelight and you bring their tunes to the forefront, to international audiences; case in point, can you tell me about the phenomenon of “Kingston Town” and your personal experience there?

UB40: The guy who wrote “Kingston Town”, this guy called Lord Creator, what a brilliant name for an artist, (laugh) he met us at the airport with his family. We done Sunsplash. And he was saying because we covered his tune, he bought a house; he could look after himself; he had medical bills, and he has had a good life because we covered one of his tunes. And that happens a lot obviously because we’ve done a lot of tunes. We are on the fourth series of Labour of Love. So the first time around, a lot of the artists who wrote the original tune didn’t really get paid; they get a couple of dollars for a track if they are lucky without royalties or anything like that. But the second time around they actually got paid so that makes us all happy.

GB: And the ultimate compliment is when you have these foundation artists singing UB40 songs. For example, the Fathers of Reggae album and how you covered “Please Don’t Make Me Cry” by Winston Groovy and he went ahead and covered one of your classics. What kind of gratification and satisfaction is that? In other words, if you passed away tomorrow would you feel as though your life and the things you’ve done have been complete or do you still feel like you have another 30 years to go?[

UB40: (Laugh) We, obviously, had a charmed life. We’ve been really lucky and we’ve made a living over all of our working lives out of music, which most people don’t manage to do, so we’re the luckiest people in the world. That doesn’t mean we still don’t want to achieve things, but I suppose we got a sense of satisfaction that most of the people aren’t going to have because we realized our dream and lived it for most of our lives which is a really nice thing to be able to say.

GB: And so what you have done is given back to the reggae family by endorsing these artists that you grew up on by paying tribute to them by making renditions of classics from the 60s and the like, bringing a modern day version to the international audience, then, practice reciprocity by inviting Gregory Isaacs or someone else to come in and do something for you?

UB40: We didn’t make the Father’s album for any altruistic reason. We made it because it would be fantastic for us to hear our heroes singing our songs instead of us singing their songs. It’s an indulgence for us I suppose; it’s a sense of satisfaction you get from hearing one of your heroes from when you were young and looked up to actually performing your music; it’s just a great feeling.

GB: And as far as UB40’s contribution to reggae music’s growth internationally: Bob Marley is gone (passed away), but now UB40 is here still forwarding the music. What have you seen internationally that we have not seen, these little communities where reggae music has become a way of life?

UB40: Not even the little communities. There are so many parts of the world where reggae has been adopted, especially the Polynesian Islands and when you go and do shows in that part of the world, which of course is beautiful anyway, you get thousands and thousands of Polynesian people turning up because actually reggae is their music, and they see us as one of the biggest exponents of reggae music. It’s just so much fun especially playing in New Zealand.

GB: Do you believe the reggae rhythm is one of the biggest influences of all time on modern music?

UB40: I’d say so yeah. Rap came from it. So many different forms of music has come from reggae. In England, for instance, you got drum and bass which is kind of like a dance music. And then you got a wave of new music coming which is called UK Garage, which is like dub step; this is big in America; a few guys have moved to America because it is such a big thing. It is like dub oriented music. Then you got bass line, which another form of English dance music; this is kind of like an African influenced music. A lot of Africans have moved over to England, and their music has been an influence in dance music. Then you got Funky House, a bass line oriented music. England, for me, is like the center of the world for new music coming out and it’s all derived from reggae in one form or another. You can take it all the way back to Bob Marley. Reggae music has had quite an influence on mainstream music as well when you look at R&B and you look at the production techniques with R&B. Timbaland and people like that, they are obviously influenced by Sly and Robbie. when you listen to a Timbaland production, it’s almost like listening to a Sly and Robbie track from 15-20 years ago, so I thing there has been a massive influence. I guess you can say that Lee Perry is the grandfather of dance music. He started with those techniques: up front drums and up front bass. Dance music took a lead from that, virtually every style of music has been influenced by reggae in one way or another because reggae is an attitude. It is not something you can pin down as one thing; it’s a general attitude towards music where anything goes but not too much. It’s about doing less and not doing more, and that is something that has definitely influenced pop music.

GB: So it’s like rather than working harder, it’s working smarter? Making your art form that much better and continually refining yourself so you don’t become stagnant?

UB40: The thing about reggae is that the hardest thing to do is to do nothing, which is what it requires. Sometimes, it’s about taking something away and that takes discipline. It’s the most discipline thing in the world; if it’s not needed, then throw it out. You have to have the basic elements necessary to make something sound complete. Just the tiniest amount of elements. As you see with R&B productions now. You don’t even get bass lines now sometimes; you get nothing but a drum track on certain tunes and you’d never have that without the implement of reggae. It’s about taking away sometimes rather than adding.

GB: British reggae has often been ridiculed as not being authentic roots music. In the 80s with the sound systems of England Saxon developed the fast style of djing, and they could command greater success than their Jamaican counterparts, what do you think the UK has done in general to legitimize reggae music as a whole?

UB40: (A deep breath. No one really wants to answer that question, really.) England has always been an enormous market for reggae because we had a lot of people come over from Jamaica in the 50s and 60s. That’s why we play the music that we do because of the dash board and the people coming over from the colonies, England used to own Jamaica; England was the mother country. They used to make records specifically for the English market in Jamaica, so England has had an effect. But reggae has gone international now; this is kind of parochial. Right now, reggae is known in every corner of the world. Jamaica can’t own reggae, and England can’t own reggae. Everybody owns it.

GB: D.U.B.40—DUB40. Is that a reality and what to you think personally can take place with instrumental or dub side of UB40?

UB40: We did actually start rehearsing to do a dub set as like an another arm of UB40, and we were in rehearsals for about three weeks. It was in the transition period between Ali and Duncan, and we kind of fanned Duncan half way through and went back to the dub stuff. But we did get about ten tunes together. We got vocal samples and everything but it is a thing that will get revived at some point. It’s really complicated to play dub because it’s all about arrangement and stuff, so it’s actually harder to play dub than to play an instrumental, you see. You don’t have a song to follow with dub, so it’s all about the atmosphere and the arrangement which is quite difficult to play. When you don’t have a song to follow, you got to count bars; eventually, you won’t. But to start off, you have to count bars because it’s not really a live form of music; it’s specifically for the studio. We want to take it live and certainly a lot of bands have been taking dub live for 20-30 years now, so we really want to do it because, in saying that, when we first started we were all about dubbing. That’s all we used to do you know because we didn’t have a lot of songs; we were all about dub. We used to come up with jazz club dibby is what we used to call it. When we made it, it’s a beautiful thing. Going back into it and trying to recreate it even though we were naïve, we put everything into every tune; it always worked you know what I mean.

GB: When No Doubt performs “All I Want To Do” how do you guys feel about big musicians playing UB40 songs?[/question]

UB40: It’s a massive massive compliment to have your music performed by other artists because they choose to do it. You don’t force anybody to do it. Of all the songs in the world somebody could choose to cover, they chose one of ours and that just makes it feel good. It’s one of those things; it’s always really nice when it happens. I wish it would happen more to tell you the truth (laugh), but even Jamaican artist have covered some of our stuff or they sample our bass line to make another tune, so it’s always a big compliment when they phone me up and ask if it is alright. I’m like yeah yeah man go for it; we never really been precious about sampling; anybody can sample our stuff. We definitely won’t take you to court over it.

GB: Brian, as a youth growing up in Birmingham, you had a love for soul and reggae. You witnessed the skinhead culture as ska, bluebeat, and reggae developed. Please elaborate on this phenomenon of that time period.

UB40: It still is to a degree, but the 50s, 60s, and 70s youth culture, it was always a really big thing. Before 1950, young teenage boys dressed like their grandfathers. After rock and roll from the states, Bill Haley and all those guys, the English really fell on top of youth culture in a big way. You dressed like your culture, so growing up in Birmingham in the early 70s, the musical stars were kind of glam rock and progressive rock, which was long hair and hippie clothes; or glam rock which was glitty like David Bowie, where guys wear make up and their sisters’ shirts. But where we lived, we come from right in the center of the city; we come from downtown where there was a huge population of people who emigrated from the West Indies, Asia, India, but particularly West Indies because England kind of demolished it in the second world war. So our play sites were bombed houses and places that had been bombed down. All our neighbors were from all over the world. There wasn’t any black culture on the television in England; in England, there were two television channels—pure white so for black youth growing up where we lived, they were kind of living the life of white kids, dressing the same. Youth culture being very important, so when the black families came over, music was incredibly important to them. That was their outlet. Where we lived we heard a lot of reggae music; we heard a lot of soul music from America; we have always been big fans of American made soul music. We had stacks of Motown and stuff. The English love music and we are a multi-racial country. There’s a lot of Irish and Scots and Welsh, and they are very musical. Our youth culture took on the guise of the rude boy thing, but we didn’t think it was second hand. We weren’t emulating anything, and we called ourselves skinheads except we weren’t Nazis. It wasn’t a racist thing; it was quite the opposite; it was celebrating West Indian music, Jamaican music, pure Jamaican music; it was a bit after ska and we dressed accordingly. It’s all down to youth culture. It tells a big story and it was a very powerful thing as well for young kids in England who are multi-racial neighborhoods. The black kids were able to find themselves, to find some identity and Bob Marley started growing tiny little dreadlocks and burning came out and reggae really started coming into its own. It became a cultural statement rather than just pop music. It was that point as well that we felt a little left out. Being white guys, we weren’t part of that but we loved the music. You dress like the album sleeves. You didn’t find guys like us carrying Led Zeppelin albums or glam rock stuff. I know that sounds really closed minded, but that’s how it was. It was our way of expressing ourselves.

GB: Speaking of Bob Marley, Robin, when you first heard The Wailers, they sounded like an R&B group singing “Blue Suede Shoes”; explain how rock steady was derived from American R&B hits and rerecorded with a different rhythm with Jamaican singers how this process takes place does the song slow down, bass line comes accented and eventually became reggae?

UB40: I’m a little bit older than the rest of the guys in the band, so I go back to the 60s and the forming of reggae, which was the rock steady period when it changed from being ska to reggae. There is a different argument about what that period was, but I think that period was right around the summer of 67 when I was about 13. The whole thing slowed down and the bass and drums became much more prevalent. Vocals became much more prominent and vocal trios came into it. Then, Jimmy Cliff was the first superstar of this era. That was when I became interested. Before that, I was into ska almost exclusively Prince Buster; he was the king of ska; he was the man making the music that the skinhead scene and the mods turned onto. He made music for them and later Desmond Dekker, of course, but you got to emphasize on the skinhead thing because it’s transmuted now. It wasn’t a sieg heil thing. No, it was a working class identity thing. It was all about working boot and jeans. Looking as smart as you could because you really couldn’t afford the really sharp suits you really wanted. The 60s mod scene was about wearing sharp Italian suits and having very shiny polished shoes. The working class kids that couldn’t afford that embraced this whole working class look, which was the rolled up jeans and Doc Marten boots, Ben Sherman shirts. It was very much a working class identity thing when it started. It was all multi-racial; my black mates had all skinhead hair dos and were wearing monkey boots. The whole racist things was decades later when skinheads were associated with the national fronts and the fascist parties. When ska was the music that had been adopted by the working class kid, the skinhead thing was about an identity thing. It was about being working class and proud of it. I was actually never a skinhead because I always tried to be a bit smarter than that. I was always a mod; in fact, we were called tanneys. We had short hair but it wasn’t skinhead; it was suits, stay pressed ever pressed trousers. It sounds bizarre talking about it, but it was an identity thing. If you were into rock, you wore leathers and grew your hair long. If you were into soul music and ska, you were a mod and you dressed accordingly. One of the things that surprised us when we started touring around the states in the early 80s is we would have guys in the crowd wearing AC/DC t-shirts, but they’d be loving reggae. It’s always been much more broad minded over here. And it’s true to say that pop music is the American musical renaissance; it comes from America and we all embraced it. We all loved it. When I turned onto Marley in 69 or 70, when African Herbsman came out which was the album that they did with Lee Perry where he wrote half the songs. That, to me, I remember bringing it home and playing to my little brothers Ali and Duncan. I guess they were 10 and 11 at that time and saying this is the future of reggae because it was so different. Because it had a militant edge. It was the beginning of politics in reggae because before that it was Jamaican pop music and don’t forget a lot of the early reggae tunes were covers of country tunes. Country was massive in Jamaica. Jim Reeves is the Elvis. To this day, he is massive in Jamaica. Peter Tosh’s ambition was he wanted to be the Johnny Cash of reggae playing country music not reggae.

GB: How about toots? Take me home?

UB40: Toots…he was into Willie Nelson and stuff. They do love their country music in Jamaica because it’s beautiful music. Country music is America’s reggae music I always thought; Cajun music was America’s reggae. It’s talking about local stuff and something everybody can dance to it.

GB: It must be a pleasure to have worked with originators of this style music can you talk about that?

UB40: When Jackie [Mittoo] (Skatalites) showed up at our studio, we didn’t invite him really. He turned up because he heard we were doing “Labour of Love” and he played on most of the originals. He just turned up one day. We didn’t know who he was; we never seen a picture of him. They are like Jackie Mitoo is at the door, and he comes in. We were beside ourselves! This is one of the originators of the music, one of our idols, and we just said, “There’s a keyboard there Jackie. Would you fancy playing on it?” He was truly a beautiful guy; he was a really lovely, lovely guy. He didn’t have a bad side to him. That had been our experience with all our heroes when we met them. They have all been really gracious. We’ve been incredibly lucky. Did you know none of us could play an instrument when we formed this band? Most kids start off in their bedroom practicing to their favorite record; we just all happen to start at the same time and none of us had a clue. I think Robin knew four chords and luckily that was the four chords we needed. We all sat there learning together; that’s twelve notes taking us. We never been anywhere; twelve notes taking around the world a thousand times and met all the people we never thought we’d meet. They do say don’t get too close to the stars because the dust comes off. I haven’t experienced that because everyone has been lovely and the fact that we idolize their music and we’re carrying on the tradition, the fact that we’ve paid tribute to their work, and they just love the fact that years later they’re getting the recognition they deserve. We often get called a white reggae band but we never set out to be a white reggae band or a political band; we just wanted to have a job, have something that we could do. That we all loved music and Ali always wanted to be a singer and that was the emphasis really. He wanted to be a singer and we are like yeah we could be a band. It’s been a really wonderful journey you know. Thirty year have flashed by; it could be months. If you said it’s been a year and a half I would believe it because that’s how it feels. We talked about it since we were kids; we always talked about it as brothers; we’ve always done harmonies. I think going to see the wailers in ’76, I think that was the thing that finally did it for me. Ali as well because we started talking about it seriously from that point on.

GB: Reggae has had a battle getting the recognition even from the category of reggae in the Grammys and later you being nominated…

UB40: I’m going to interrupt you there about being nominated in the Grammys because some time ago we were doing an interview, and this guy who does the reggae nominations for the Grammys says his proudest moment was keeping UB40 out of the Grammys. Big deal; we are not into it for any rewards. We’ve never been particularly fond of the filthy look. It always kind of ruins the music, and we got all the accolades that most black reggae bands got out of Jamaica, so I find it kind of confusing we’ve turned down more awards, haven’t we?

GB: But you’ve brought this music to places it has never been you’ve brought it to places like Russia and New Zealand for example.

UB40: Yeah, because we saw ourselves as ambassadors of reggae, and we were going to take reggae to every corner of the world. Of course when we got there, we discovered that reggae was already there. Anyway, the truth of the matter is reggae has become a world music; I can guarantee you that every corner of the world we go to, there is a reggae band. There’s a local reggae band, so it’s traveled the world anyway. We’ve just played a part in that; we didn’t take reggae where reggae has never been. We’ve taken UB40 where UB40 has never been. We were serious about what we were doing, not taking ourselves serious but serious about the work. So we always tried to get the best guys to work the best label. We tried to get the label to believe in what we were doing, and we worked hard. If we had interviews to do at 6 o’clock in the morning on a station in Palm Springs, that is where we would be. Whatever we had to do we would do, and I think that gave us a bit of a leg up. I think the fact that half the guys in our band were white guys, we had a white singer, I think that opened a few doors. By the 80s I think it was frightening a few people, well not frightening them; they just didn’t quite understand. I meet a lot of kids into reggae, with dreadlocks who speak like they’ve been living in Kinston for 35 years. Fair enough; maybe that’s their way into the music. It’s not a religion; it’s music. Rastafarianism is a religion, and we are pure devil worship (laugh). We were the alternative to the whole thing that grew with Marley. Marley exploded throughout the 70s and when he embraced the Rastafarianism, his lyrics and music, the two—reggae and Rasta—became inextricably linked. People who were turned on to reggae in the 70s believed that was reggae was, but of course, reggae was going in the 60s before Rasta was even involved. In fact, most of the musicians who were Rasta’s in the 70s had short hair in the 60s when they were looking like soul artists. Don’t get me wrong with what I’m saying. The Rasta thing is incredibly important, really emancipated, and started giving some history, especially where we lived and it’s made the world a better place and has opened a lot of things up. We’ve seen a lot of changes in 30 years. It’s been getting better were getting there slowly.

GB: There was something called the Two Tone ska revival in England; can you elaborate on that?

UB40: Sure. It goes back to your earlier question about did we get into reggae and soul. Youth culture. So you have the punk explosion in the 70s, and that was a culture that came to America. It was exploited and it was time for something new with the punk thing. That kind of freed up everything, no racism, no isms. Punk music, the great thing about it is that anybody can play. You got together with your pals and made a great noise, but when you wanted some music in the dance hall, they played reggae, The Clash. Marley was massive with the punk kids which gave a great opening for us because every place was punk, but they played reggae. That’s where we’d hang out and smoke a spliff and listen to the music we wanted to hear. Out of that, the kind of Two Tone thing and suddenly we would see these little kids. We would see The Specials. They were dressed up like we were ten years previously, and we were like, “No way! This is great! Look at these guys!” We were playing reggae. You know two tone was incredibly popular; if fact, I think two tone opened the doors for us really, even though we weren’t part of that. We were kind of dragged along on the shirt tails. We weren’t holding on; we were pushed along really. They started paying tribute to some great music that had already been released but people just hadn’t heard it. It was proving how great it was and there we were.

GB: Case in point, Toots with “Monkey Man”?

UB40: The first reggae record I ever heard on the radio. It was on the Luxemburg radio, the pirate radio. You couldn’t get it on the BBC, but I would listen at night with a little transistor radio. I used to have it under my pillow because the power play for the week would be Toots and The Maytels. Luxemburg revived everything. They were reviving the Prince Buster stuff; they were reviving Al Capone, playing Madness and The Specials. It was brilliant, but we steadfastly refused to become part of that even though we played the same venues. We played Rock against Racism with them. We were friends with all of them. Rock Against Racism was a big anti-nazi thing by the anti-nazi league because by now there was this new wave of young Nazi doing the Hitler sign and all that stuff. They asked us to do a single on Two Tone because of that. They would say just do a single on Two Tone because it would be a hit. Everything on Two Tone at that time was a hit. And we kept saying thanks but no thanks; we were so stubborn. We just didn’t want to be labeled as part of that revival. And things became so conservative, but we were so dichotomous. It served us well because it disappeared, all that Nazi stuff just went away, but it’s starting to come back again thirty years later, isn’t it?

GB: So reggae music is a dance music as opposed to a King Selassie music?

UB40: Absolutely. Reggae is the dance music of Jamaica. Of course it developed and changed throughout the 70s because of the influence of Marley, nobody else but Marley and the growth and popularity of Marley, but people forget that ten years before that it was the dance music of Jamaica. There was all these people who were making reggae before it was Rasta music.

GB: And you consider to be sexy?

UB40: It’s the sexiest music there is.

GB: And you do it Brian because you make people happy?

UB40: (Emphatically) It makes me happy. I always thought music is very liberating for the musician because nobody has to listen to you. They can turn you off the radio, they don’t have to buy your record, if you’re on the TV they can change the channel. You see music is emotional communication between you and strangers. You become their power without even knowing their name. You can shake their hand without ever knowing their name. It’s a wonderful thing.

GB: What I love about UB40 is that you are always out there speaking the truth.

UB40: Except when we are lying (laughs all around).

GB: One of your albums, Cover Up, was dedicated to the need for global AIDS awareness and the UN’s fights against HIV and AIDS. Islands such as Jamaica are reluctant to address this problem because they don’t want to lose the tourist trade. Would you talk about that as a band you are writing love songs and tackling social issues that affect the human race?

UB40: Whew! Well some years ago we were asked by someone from the UN if we would become part of a campaign to popularize the AIDS movement. We weren’t ambassadors, so we wrote Cover Up and we asked a lot of people to do a version of it. We always prided ourselves with saying something with the songs. We were never really any good at writing love songs. There are literally thousands of great love songs. Now you try writing a love song better than any of those love songs. You can try but it’s difficult. The love song is the hardest song to write. But we do write songs that say something, and our political conscious revolutionary zeal has never gone anywhere. It’s just been out shined by these incredible pieces of art that was made in Jamaica. People often say you only do covers but the truth is a cover is just a song everybody knows. You cover a Beatles song. We were doing tributes of Honey Boy’s single that sold 500 copies. I don’t ever see us as covering songs; I see us as paying tribute to these unknown songs. Well, some of us reggaephiles know the songs, but now thousands and thousands of people know these songs. They dive back in and get the original. So labels like Trojan has been reinvigorated and Treasure Island. We are very proud of that, but to the critics, it only shows their ignorance when we only done four albums of tributes and 21 original albums. If they want to call us a cover band so be it. It’s just as stupid as calling us a white reggae band when there are four black members [out of 8 total members] of the band. We can live with; it’s not going to make us give up or retire in a way. We dug our own hole because we paid tribute to some of the greatest songs ever written. We’ve had more hit singles in England than the Bee Gees. I’ve heard we had almost 600 hit songs. I don’t know where I was when this was happening. Must have been in LA (laughs). But we don’t take ourselves seriously, we take our music seriously. That is the best advice I have for young bands: take the music seriously, not yourselves because there will always be a critic; there will always be somebody who doesn’t dig what you do.

GB: Talking about human causes, there was Famine in Africa UB40 participated in the “Starvation” single. Can you go ahead and restate your participation; moreover, how you continue to put food on the table of the songwriters too who wrote those songs and are receiving money for the songs you tribute and are now making a good living as a result…

UB40: We should interview you about us (everyone laughs). I’m not going to stand here and blow my own trumpet and say aren’t we great (laugh. Kind of awkward, though), and say aren’t we great. We don’t do things like that for recognition. We do them because we think their right. We do them because we think we should do them. I don’t have a record of the social causes that we’ve done; you have a record of the social causes that we’ve done (laugh again). We don’t think about it. Every now and then something winds you up enough to do something about it. We were asked to work on the Pioneer’s song, “Starvation”; in fact, The Pioneers came and worked on it with us. We were just one of the people asked. Of course we did it. It’s a great thing to do that kind of stuff, and I don’t mean in a self-righteous sense. When you do those things, it’s like hanging out back stage at Madame Tussauds. Sadly, every time we are involved in those things, we are always disappointed by the lack of weight, the lack of difference these things actually make. Also the motives the people have for actually being there. It’s fairly obvious when you do these things like Live Aid, 90% of the bands that are there are there because it is a good PR exercise. That’s depressing. When you get Whitney Houston coming on the Free Mandela concert dropping Coke A Cola banners over Mandela’s picture, it makes you wonder why the hell you’re there when other people’s motives are quite disgusting. Those were incredible ideas that became perverted so quickly. I mean they made a difference; I really know they have. But it gets so commercialized that you question whether you want to be a part of a thing like that. Every now and then you do it because you like the original reason they started, but it always ends up as a commercialized pile of crap really. The last one we did was Live Aid. We were asked and of course we did and backstage there was a television village. There was a media village. You had to do a thousand interviews; Bill Gates paid for the backstage. So there was Live Aid going out to about 8 billion people worldwide raising the issue of starvation, and backstage you can get mojitos and lobster. I may sound like I’m being a killjoy about it, but there was just a serious dichotomy. I felt like saying, “You know Bill Gates, you know the two million dollars you spent on backstage, just go and give it to a hospital in Africa. Fuck those people backstage; they all got more money than they need anyway.”

GB: Can we touch on incarceration, Gary Tyler, “Rainbow Nation”?

UB40: It’s been thirty years since we made Signing Off. We talked throughout this interview about a zeal for protest. We were always proper protestors. Jimmy wrote a song about a guy named Tyler who at that point had been in prison for 5 years in Louisiana. He was a schoolboy on a school bus and somebody got shot so they had to catch somebody. We wrote a song thirty five years later. He is still in prison, so Jimmy wrote the follow up song, “Rainbow Nation”; it was gong to be called “Tyler Two” or something. His freedom campaign got in touch with us and said, “Guys. Please don’t do anything that will make the judiciary down there look bad because they will just lock down. They will just close ranks.” we were going to put a photograph of him on the cover of the album. They begged us not to and we said, “Of course,” because they were in the appeal process after all these years. They asked us not to make a big deal about it because they didn’t want to antagonize anybody, so we renamed the song “Rainbow Nation” and did it kind of low key. He is still there of course. The appeal was turned down so he’s still in there now.

GB: But you’re not afraid to speak out against inequalities?

UB40: That’s all we’ve done since we starting writing songs. We are not afraid to say about things that annoy us, things we are passionate about. We celebrate your freedom of expression, freedom of speech. We have to fight in England for it. We’ve always felt it was our responsibility to write about it. We can’t write love songs; if we could, we would probably on the radio more. Things have changed, though. We got caught smoking a joint in 2002—after 9/11—it’s something we’ve been caught doing before. We’ve all been in prison cells in other countries for doing it, but that was before 9/11. After 9/11 your home security just lowered the bar. It was suggested that our lyrics and our politics aren’t helping us.

GB: Well there are reports that you have a file in England with the agency that is like our CIA; you are being watched.

UB40: We’ve always had a file; we’ve been watched by MI5 [England’s Secret Service] for 15 years because a guy, an agent, became a whistle blower. You want to know UB40s proudest moment: when we found out that us, John Lennon, and The Sex Pistols were on the same file. That’ll do (Jimmy said this so proudly, with his chest sticking out); the MI5 monitored our phones; we were photographed for 15 years. We write songs, been writing songs, for 30 years. We can write a million antiwar songs; it still hasn’t stopped war. I mean Tyler is still in prison, right? Don’t get us on war though. Our countries were built on war. They send our youngest and brightest lads, who should be in college learning to read properly, they send them off to get killed and lie to them about why they are going. They tell them they are fighting for freedom. They think they are fighting for their family back home. No. They are not! They are fighting for profits and vested interest—oil. It’s the biggest industry that has ever existed—war—and it is still is. The trillions that are being made and the hundreds and thousands of innocent kids getting killed, being pulled out of school, being put in the army and then turn them into a hero. Outrageous! The average age for soldiers in every war is about 19; that’s it! You know why they don’t put guys my age in the Army is because if somebody told to go shoot somebody, I’d shoot the person who is telling me to kill someone! That’s it! It’s all over. Let’s go home (a serious and very somber, almost awkward silence came over the entire room). I’m serious! If anyone tried to take my kid off to war, I’d shoot them as well. I don’t love patriotism. I don’t mean to insult American ideology, but patriotism scares me to death. I think it’s a big disguise. I love freedom. I love free speech. I love people celebrating being happy and safe and secure, but I don’t think there is a flag that has ever done that! Ever! They just wrap dead bodies in flags. That’s all they ever been any good for, you know? Give a purpose for a death. Fucking waste! (In addition to the extreme silence throughout the room, at this point, I will refer back to the comment made by us after the first question of the interview.)

GB: (Extremely awkward silence) Wow! (Something had to be done to bread the silence)

UB40: Sorry. We were talking about music weren’t we? I probably shouldn’t have said that. Anyway our latest record (He said this jokingly and we all laugh to break the seriousness).

GB: One last thing, one of the attributes of UB40 that I have always admired was the ability of the band to have this unique sound. In the early days, there was an engineer and producer by the name of Ray Falconer, who is a mate and family member; who we miss dearly. Would you be so kind to spend a minute to talk about his life and his impact on the UB40 experience?

UB40: Ray Pablo Falconer was Earl’s, the bass players, brother. He couldn’t play an instrument, but he wanted to be a part of the party. He started out knowing as little as we did. He had a love for the music and was greatly influenced by dub. From day one, he was our mixer from our first shows right until he died; much more in our live records even though he got coproduction credits for our records. He was the ninth member of our band. Whenever we were on stage, he was in control. Everything that went out up front was him. He was a bit sort of Mad Professor. He was just into what we were doing, and in the early days, that’s what made our live performances such an event. I was because of the contribution he made up front. It left a massive hole when he died. It took us a while to get over it. He was our friend. That was heavy time for us, and it took us a long time to find engineers who could (pause), well, nobody ever filled the hole; we just made do with very good engineers.

GB: And then the most recent departure with your brother, Ali, and Mickey, the keyboardist, but the band perseveres despite adversity, can you shed light on that?

UB40: You know UB40 is a big organization. We been around for 30 years; we employ a lot of people. There are people that have worked with us for 20 years 25 years who have families and mortgages and responsibilities. So when Ali decided to go solo to try something new for himself and Mickey went with him, we had to carry on for a lot of people. It’s not about us; it’s about everybody. But it never really occurred to us to stop because even though it was like losing a limb, it was more emotional than musical. Not to put anything on Ali; we lost our lead vocalist, so we had to find someone that could fill his shoes and maintain the spirit of UB40. Luckily, I had another brother who had a similar tonal quality that allowed us to maintain the same shape and sound of UB40. Duncan’s presence and energy allowed to keep going.

UB40: The thing is we love doing what we do, and the fact that we might lose a member or two is not going to stop us from doing what we love doing because we are not going to do anything else. God forbid if we had a plane crash and lost two more members of the band, it wouldn’t be the end of UB40. UB40 is an institution. It will go on until audiences stopped showing up, and they haven’t stopped yet. That was the litmus test with Duncan. He’s been with us for several years now and the audience’s reaction has been really kind to us. We are told that we still sound like UB40 even though there is an obvious difference between Duncan and Ali. There’s a lot of bands that couldn’t do without a lead singer because they carried the image of the band, but we’ve never had a leader we wouldn’t allow it we were all mates growing up we didn’t come together to form a band, we were a band of brothers.

Thanks to all of the guys of UB40 for sitting down with ATOD Magazine to do one of the most compelling interviews yet. Thank you for having a voice you sound so eloquently and for all you do to open minds and inspire change.

You can pre-purchase or download songs of their new album, “Getting Over The STORM” here: Amazon | iTunes

Greg Barraza is an ex Pro Skater, a college Professor of English, and one of ATOD Magazine’s most revered writers and interviewers.

ABOUT UB40

INTRO

The story of UB40, and how this group of young friends from Birmingham transcended their working-class origins to become the world’s most successful reggae band is not the stuff of fairytales as might be imagined. The group’s led a charmed life in many respects it’s true, but it’s been a long haul since the days they’d meet up in the bars and clubs around Moseley, and some of them had to scrape by on less than £8 a week unemployment benefit. The choice was simple if you’d left school early. You could either work in one of the local factories, like Robin Campbell did, or scuffle along aimlessly whilst waiting for something else to happen.

By the summer of 1978, something else did happen, and the nucleus of UB40 began rehearsing in a local basement. Robin’s younger brother Ali, Earl Falconer, Brian Travers and James Brown all knew each other from Moseley School of Art, whilst Norman Hassan had been a friend of Ali’s since school. Initially, they thought of themselves as a “jazz-dub-reggae” band, but by the time Robin was persuaded to join and they’d recruited Michael Virtue and Astro – who’d learnt his craft with Birmingham sound-system Duke Alloy – the group had already aligned themselves to left-wing political ideals and forged their own identity, separate from the many punk and Two Tone outfits around at that time. The group had nailed their colours to the mast by naming themselves after an unemployment benefit form. Their political convictions hadn’t been gleaned secondhand either, but cemented in place whilst attending marches protesting against the National Front, or rallies organised by Rock Against Racism.

The PRESENT

At the beginning of 2008, Ali Campbell decided to leave the band in order to pursue a solo career. With a minimum of fuss, he was replaced by another Campbell brother, Duncan, who has a voice that’s virtually indistinguishable from Ali’s. Duncan had been invited to join the band at their inception, but declined. However, some thirty years later alongside the other UB40 vocalists he has made his presence count on the latest album “TwentyFourSeven,” which received widespread acclaim on its release during the summer of 2008. Following on from “Who You Fighting For,” “TwentyFourSeven” was again recorded “live” in the studio, and thus showcases UB40 at their best. Not for the first time, the choice of material was dominated by the kind of searching, political messages they’d long been famous for. Songs like “Rainbow Nation,” “End Of War,” “Oh America” and “Securing The Peace” rank alongside their best-ever reality tracks, except with guest singer Maxi Priest taking over lead vocals on “Dance Until The Morning Light” and a cover of Bob Marley’s “I Shot The Sheriff,” the mood is celebratory as well. Freed of the need for hit singles (if not hit albums), UB40 sound rejuvenated, as if they’ve rediscovered the creative spark that inspired them in the first place. The results make essential listening, reaffirming their reputation as the world’s most successful reggae band as they continue to reach out to audiences that are impossible to categorise by race, age or nationality.

This year UB40 have had yet another busy tour schedule including such places as, USA, Italy, Germany, Spain and Slovakia to name a few. In between this extensive touring schedule they have also been having a great time recording “Labour of Love IV,” which they have now completed and it is due for release in February 2010. Along side this they have also made time to do a benefit gig at the Rainbow pub in Digbeth, Birmingham. The gig that took place on the 3rd of November was to help the Rainbow raise money to sound proof their roof as they had a noise abatement order slapped on them by Birmingham Council. Needless to say this was a resounding success and not only raised a lot of money for an extremely good cause, it gave around 500 fans an opportunity to see the band up close and personal for the first time in many years. UB40 are now currently in rehearsals for the much anticipated UK tour which begins in Killarney on the 19th of November.

The DISCOGRAPHY