If You Build It, You Can Change The World

by Tyler Dean

IMDB | Facebook

“Innovative” is the last word one thinks of when juxtaposed against the grassy plains, empty storefronts, and abandoned primary schools of Bertie County’s very own small town of Windsor. Windsor, where the biggest milestones are a miniature-sized oil industry and a Domino’s Pizza, it isn’t hard to grasp the opening words to Patrick Creadon’s award-winning documentary If You Build It that Bertie County is an exemplary arena of the demise of rural America, and, more importantly, the nascent disregard its people have for forward-thinking problem-solving in the face of an endless vista of possibility. More than anything else, it’s this diluted sense of self-worth in the town of Windsor and its inhabitants that brings out the stark opposition at the very core of Emily Pilloton and Matt Miller’s Studio H program. More than simply a multi-phase platform for creativity, Studio H invites participants—in this case, a motley collection of 16-year-old high school students—to take on an archetypal subject, dissect its structural integrity, and infuse it with their own idiosyncrasies to ultimately project a whole new vision onto something as simple as a chicken coop.

Creadon starts If You Build It off by introducing us to Pilloton and Miller; how they’ve recently taken on a job as shop class teachers for the town’s local high school. Seasoned architects themselves, the film weaves between scenes showing a house Miller had personally designed and built in Detroit some years before. Everything seemingly appears to be smooth sailing, that is until the town’s school board forces Superintendent Dr. “Chip” Zullinger to step down after making a series of recent rapid-fire changes to the district meant to inflate its fledgling school system. This, of course, included Pilloton and Miller’s Studio H. Wanting more than anything else to prove that their program will work, and not with a fervent desire to make a change in the community, the pair is left with little choice but to give up their offered salaries for the first school year. Free of financial obligation (it’s clear from the get-go that the board could care less about how the students will fare), the board acquiesces their request to stay on. The financial fallout, although not a devastating blow, complicates matters since Pilloton and Miller now only have government grants to keep them afloat in the coming months. However, as becomes clear, this only motivates them further to prove that they, and Studio H, have a place in Bertie County.

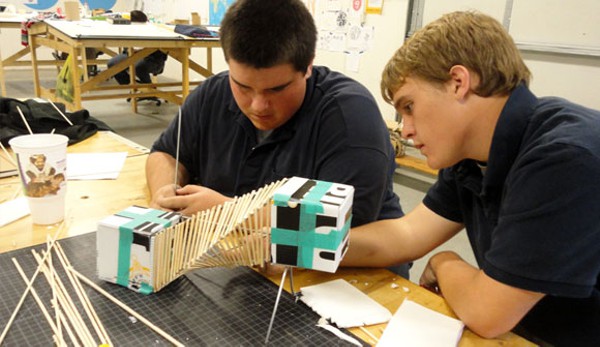

The film is split into three distinct sections seamlessly tied together with the help of Oscar-nominated editor, Doug Blush, and appropriately, iconic graphics. Following Pilloton and Miller, we meet the wood shop class students: boys and girls who are depicted at first to fit the uncertain, marsh-riddled town stereotype of drowning in muddled obscurity. Students who seem so woefully different from what we—especially in Orange County—expect or are used to when it comes to 16-year-olds (arguably), but who we very quickly realize are as different from us as we are from ourselves. During those first few days of class, the students are tasked with identifying what makes an object what it is, how it works, and eventually equip them with the knowledge to mold and fire a clay water filter made of organic material. Candid moments, captured on one student’s handheld camera and cut into the film, more or less reveal what you might expect from students who are used to taking physical education courses online (yeah, we don’t understand how that works either). However, despite the private protestation of students to the contrary, there’s a spark of ingenuity; of pride that begins to seed and germinate among the collective.

Studio H’s approach to constructing any type of work can be boiled down to six steps (more like a collective of stepping stones, in that you aren’t limited to beginning on any one, in any particular order): Research, Ideate, Develop, Prototype, Refine, and Build. Although Pilloton explains this to the viewer earlier in the film, it isn’t really until the wood shop class takes on its second project – one I mentioned earlier – which is the concept fully executed as a chicken coop. This is where we really begin to see the creativity of the students blossom, where the film does a markedly impressive job of oscillating between the subject that is the progression of the class project and the students themselves. I chuckle to myself at the sight of one particular coop model, reminiscent of a Frank Gehry design. Even the student who had come up with the idea was skeptical, mentioning that he just started putting triangles together and said design is what came of it. When the students finally build a working structure of their miniature models, the result of the Gehry look-alike is awe-inspiring.

One thing viewers will notice as Build It progresses is that as the film matches the students’ progress, audience members will begin to confuse the onscreen elation and sense of accomplishment of the boys and girls, with their own. Blush, staying for a Q&A with a regrettably sparse audience following the screening, probably says it best when he quips that, as an editor, he feels like a part of the characters’ life stories when it comes to documentaries. I would add that it is the same with an audience member, with whom, not surprisingly, the editor acts a conduit. I’ll be the first to admit that after watching Build It, more than anything else I wanted to go out to my nearest Home Depot and build something with my hands, rainy weather be damned. Creadon, always behind the camera and somehow managing to be everywhere and yet nowhere, masterfully stitches us into this sanguine space and time, even in the midst of decaying rural communes, dilapidated infrastructures, and an Alighieri-infused frontier of uncertainty.

The third section, making up the bulk of the film, starts by taking us back to Detroit and the aftermath of Miller’s efforts. After completing construction on the house he’d designed, we learn that it was granted to a family in need. However, the woman who received the house failed to make the monthly payments (the monthly fee was much less than what she was making at the time), and Miller ultimately had to evict the family after nine months. It sets the stage for North Carolina; for their final project—one which extends into, and well past, the Summer break—the students are tasked with designing a Farmer’s Market venue that will be gifted to the public. The question, of course, is whether or not they will be able to succeed. And even if they do, what will become of this “last stand” against the pantomime machinations of a town going through its dying breaths? Will it be a repeat performance of Miller’s efforts with the granted house? At this point, viewers will realize that this story is no longer about Studio H, or Pilloton and Miller, or even the students. It’s about the drive and change that a force as small as ten 16-year-olds, boys and girls with no real prospects, with futures as barren as the fields they cross on the way to school, can do when tested; the changes any one person can make when challenged. Build It, then, is simultaneously a constructive criticism not only of an education system which works to hinder, rather than help, its students, but rather that all institutions around the world fail on the most basic of levels of aspiring to inspire.

So what does happen with the Windsor Farmer’s Market? You’ll just have to see the film … or visit here.

I can’t help but stress the irony of having used the word “simple” at the beginning of my recollections on this film; If You Build It works with a meticulous clarity to cover a subject that is altogether unclear, that is, the ambiguous chop shop freedom afforded to the young minds of this country, unbridled by societal constraint, politics, or even familial situations. The question that needs to be asked, and the driving force of Creadon’s film, is who will challenge them?

“IF YOU BUILD IT follows designer-activists Emily Pilloton and Matthew Miller to rural Bertie County, the poorest in North Carolina, where they work with local high school students to help transform both their community and their lives. Living on credit and grant money and fighting a change-resistant school board, Pilloton and Miller lead their students through a year-long, full-scale design and build project that does much more than just teach basic construction skills: it shows ten teenagers the power of design-thinking to re-invent not just their town but their own sense of what’s possible.” [IMDB]

The Orange County Museum of Art is located in Newport Beach, near Fashion Island, at 850 San Clemente Dr., Newport Beach, CA 92660. Hours for the museum are: MON-TUES, closed; WED-SUN, 11:00am-5:00pm; THUR, 11:00am-8:00pm.

Now in its tenth season celebrating the cinematic works and of emerging and established independent filmmakers, OCMA and the Newport Beach Film Festival present the 2014 Cinema Orange film series. Films will explore art, design and cultural icons. Interactive question and answer sessions with filmmakers will follow select screenings. Cinema Orange is organized by Leslie Feibleman, director of special programs and community cinema, Newport Beach Film Festival.

Follow ATOD Magazine™

This article has been inspired by our friends at: