Get Lost in the Folds of Reality’s Subconscious with Sarkisian & Sarkisian

photographs by Tyler Dean

The Orange County Museum of Art opened its doors this past weekend in Newport Beach to the aptly titled, yet deceptively simplistic, Sarkisian & Sarkisian: a father and son co-exhibition of works spanning a combined fifty years, from as early as the 1960s to today. Originally thought up as a survey of one Peter Sarkisian’s video installation work over the last twenty years, it was decided by OCMA Interim Director and Chief Curator Dan Cameron that parallels seen between Sarkisian’s work and that of his father, Paul, warranted a side-by-side unveiling of the two masters’ crafts, in a collective of astonishing pieces that perform double helixes around one another without ever really colliding or crossing paths. Not quite eliding reality and perspective altogether, Sarkisian & Sarkisian elevates artistic thematicisms reminiscent of titular maze-like ambiguities of the mind, while underlining the more acute sensibilities of an individual lost in today’s angst-ridden, media-driven communes. With pieces of art that effect rather than simply affect, and works that overlay itself within and throughout a reality you thought decipherable, the kinetic energy of the most recent exhibition oozing down the white-washed halls of the Orange County Museum of Art is a refreshing recourse from the normalcy inherent in everyday acrylic and oil splattered canvas.

Going into the day of the opening, I have to admit that I’m not particularly sure what I will be getting myself into. Art appears to us in many different forms, whether it be architecture, paintings, film, music, and beyond, all of it constantly changing, morphing from one medium into another, challenging our expectations. I can’t say that my knowledge of the art world is any more nuanced than the average person on the street, but I know what I like, and that tends to be a more than adequate signpost for most. Personally, I enjoy art that grabs the viewer, involves them in a way that isn’t so much actively passive … but passively active. There’s something deeply unsettling about a piece when its functionality is revealed only by the viewer’s conscious efforts to not get sucked into surface paradigms—that is, attempts to shift one’s attention from the ambiguities of pictorial edification to a simple instruction in surface study—and to say that Sarkisian & Sarkisian, especially the latter, basks in the upending of these nightmarish soliloquies, would be an understatement.

Upon entering the museum I come across the first of the exhibit’s hosted works, Untitled (Spoons) (2009), by father Paul Sarkisian. An art piece of relative familiarity, the black and white, zig-zag of the paper on wood panel initially appears to lend itself to a very abstract sort of illusions—upon closer inspection, what I mistake for a series of bulbous lines and arcs turns out to be an endless assortment of spoon silverware. It’s this “stop and smell the flowers” sensitivity to detail on the part of the artist that I come to find allows the viewer to project his or her thoughts, emotions, and experiences onto the piece, and gather meaning, rather than simply staring at a bewildering paint-splattered canvas. It’s an important lesson in perspective, one which will help you immensely as you navigate the darkened halls of this exhibit’s gallery.

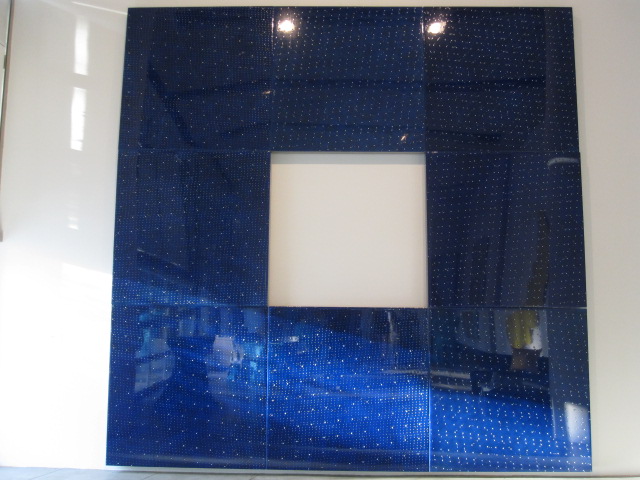

As I continue my initial walk-thru and viewing, I find that in some cases there isn’t even a canvas to be looked at; several of Sarkisian’s more recent works—Untitled (blue 8) (1999) and Untitled (blue/yellow42) (2005) come to mind—utilize resin epoxy and polyurethane in what has been said to be an effort—a successful one, I might add—on the artist’s part to explore the qualities of surface in abstract painting. Quite the transformation when considering one of the patriarch’s earliest works, Untitled (El Paso) (1972-74); acrylic on canvas, the best way to describe this piece would be to imagine yourself walking down a storefront-lined city street on a hot afternoon. You turn, approach a glass door leading into a shoe store, reach for the handle, and suddenly find your hand pressing up against a priceless piece of art. As life-like as it is in size, it’s a guarantee that you’ll just as likely fail to notice that the floor-to-ceiling piece is in fact a painting and not a blown-up photograph. Pigeon-holed as “photo-realism”—it wouldn’t be much later that Sarkisian would take his wife and a capricious seven-year-old Peter to the outskirts of Santa Fe. Despite subsequent decades of self-imposed exile from the artistic establishment, the form of illusion that overtook Untitled (El Paso), this trompe l’œil, or “fool the eye”, that so eloquently tied together the sturdier machinations of Paul’s work (and continues to do so), would come to blossom within his son Peter, and his “canvasses of light.”

In point of fact, there appear to be many correlations between father and son, perhaps the most intriguing being that of their shared affinity for casting aside commercialized culture. Originally a film directing student at the Cal Arts institute in the 90s, Peter Sarkisian broke away from what might have been a promising career in filmmaking after a disagreeable stint on the music video scene. Not too long after, he was approached to try his hand at producing video installations, culminating in what could be described as a simultaneous celebration and condemnation of perceived realities. For example, one of his earlier pieces, Gathering (1996), shows the leveling of a pair of martini glasses at chest level, with the visual of a hand (presumably the “viewer’s”) holding its stem that can only be seen when you look down into the glass’ contents from above. Coupled with an audio track of mingling men and women holding conversation, the experience becomes a mind-boggling exercise in art’s transporting qualities while retaining a certain sense of mocking awareness towards the viewer.

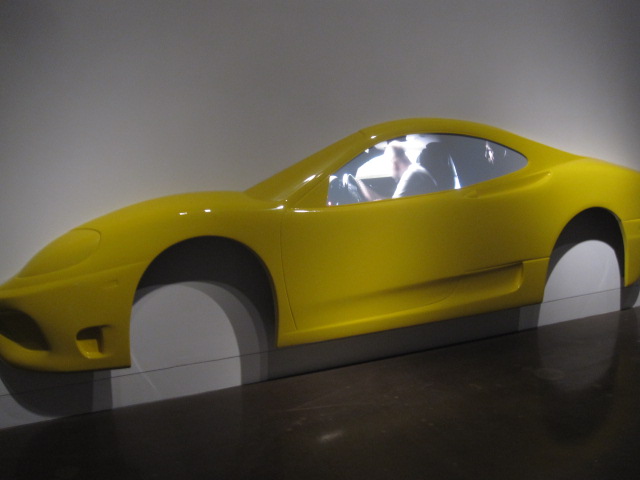

Not surprisingly, it’s this abject affectation of cultural norms and assumptions that seals the viewer’s fate. In a twist that most likely everyone saw coming, Registered Driver Full Scale #1 (2010) drew some of the most stares this evening. Described as a “driving lesson from hell”, a full-size model of a Ferrari Modena serves as the vehicle for a commentary on the ever-interesting idea of the “hyper realism.” The fears of a societal Gen-Y, when combined with spatial limits in the form of a virtual reality video game playing in the backdrop behind a Sarkisian at the wheel, elevates a simulacrum of reality where cars get blown up, people are run over, and loved ones sitting in the passenger seat won’t suffer from whiplash, all without so much as a scratch to the driver—in short, a reality where people believe that consequences don’t exist, or act like they don’t. It seems silly on paper, doesn’t it? Imagine if people actually started living that way!

Oh.

If this all sounds like a mouthful, you haven’t even begun to comprehend. With almost fifty pieces between them on display, Sarkisian & Sarkisian doesn’t just pull back the veil, they rip it off and unravel it before your very eyes. From April 13th through July 27th, you’ll tip-toe the line between experience and experiencing, at the Orange County Museum of Art.

The Orange County Museum of Art is presenting the long-overdue California survey of video artist Peter Sarkisian (b. 1965, Glendale, CA) in the exhibition Sarkisian and Sarkisian, which also includes a survey of the artist’s father, Paul Sarkisian (b. 1928, Chicago, IL), a member of the avant-garde movement in Los Angeles in the 1950s and 1960s.

For the exhibition, OCMA Interim Director and Chief Curator Dan Cameron selected 23 video sculptures by Peter Sarkisian along with 22 paintings by Paul Sarkisian to develop a thematic bridge between the separate bodies of work; tying together two accomplished careers that achieved distinctly different practices.

The exhibition is on view April 13 through July 27, 2014. Museum Hours include: WED-SUN 11-5PM; THURS 11-8PM. The Museum is closed Mon-Tues.

Significant support for the exhibition is provided by Dick and Dottie Barrett and the Levy Foundation.