Sitting Down with Giles Foden

The Art of Words and the Value of Story

Interview by Ruth Cuevas

[dropcap letter=”R”]ecently, I had the pleasure of sitting down with Giles Foden, the author and Professor of Creative Writing at the University of East Anglia in England. In addition to several articles, he has published three novels and one work of narrative non-fiction and is perhaps most well known for his novel, The Last King of Scotland.

These days, Giles spends most of his time as a university professor, teaching others how to write. Due to his unique experience in Africa, he has been called on for his expertise on the culture and environment and has authored several reports for private companies as well as provided briefings to British Diplomats assigned to African countries. Giles also worked as literary editor for The Guardian in London and has served as a judge of the MAN Booker Prize and the IMPAC Prize. His writing has appeared in the New York Times, Granta, Esquire, Vogue, Village Voice, and the Washington Post to name a few. He continues to write travel pieces for such magazines as Condé Nast Traveler. ATOD Magazine met up with Giles in Germany where he shared insight on writing, what its like watching one of his stories on the big screen, and offered advice on becoming a travel writer.

These days, Giles spends most of his time as a university professor, teaching others how to write. Due to his unique experience in Africa, he has been called on for his expertise on the culture and environment and has authored several reports for private companies as well as provided briefings to British Diplomats assigned to African countries. Giles also worked as literary editor for The Guardian in London and has served as a judge of the MAN Booker Prize and the IMPAC Prize. His writing has appeared in the New York Times, Granta, Esquire, Vogue, Village Voice, and the Washington Post to name a few. He continues to write travel pieces for such magazines as Condé Nast Traveler. ATOD Magazine met up with Giles in Germany where he shared insight on writing, what its like watching one of his stories on the big screen, and offered advice on becoming a travel writer.

Tell me about the process of writing The Last King of Scotland.

The novel took about six years to write and another six to publish. I began writing in ’89-90 and finished in ’96. As you know, the publishing process is a long one. It was published and then in ’98 it won the Whitbread First Novel Award. Much of that time writing was re-writing, until I felt it was right.

When writing a historical novel, how do you determine what you’re going to keep and what you’re going to fictionalize? Do you use an outline?

You want to have a historical frame and then have your story inside it. You want to ask, “How can I insert my story into this frame?” Outlines are useful and I use them all the time but you have to be careful because they can become a kind of straightjacket. Basically, you want to have a historical framework and make sure your story fits inside it. It was really after the millennium all these issues doing with representation started bubbling up. It’s more about fitting into an existing tradition of a historical novel that goes back hundreds of years. That tradition existed long before our current concerns about facts.

How about seeing it on screen?

Certainly the movie takes a lot more liberties with history than the book. There were a lot of interviews conducted to create an accurate portrait of the character, Nicholas Garrigan. He wasn’t really represented the same on screen.

As soon as your books are published, an agent goes about trying to sell it. This particular book was turned down 19 times before someone picked it up and then most of the film people turned it down but I was lucky that someone believed in it and picked it up.

But, I was very lucky. I was lucky that I had some really clever producers who are really good at what they do. The producers were Andrea Calderwood, Lisa Bryer and Charles Steel – they were fantastic. I was very, very lucky that it happened the way it did because it could’ve easily been a very “shlucky” movie. Even though there were moments when they took liberties with the story, I was lucky that it was well made in the end.

The only thing in the movie that is really not accurate is that Nicholas Garrigan has an affair with Idil Amin’s wife. In the book, the Scottish doctor has an affair with the wife of another doctor. The historical fact is that the Ugandan doctor had an affair with one of Idil Amin’s wives so that’s where the story comes from. The truth is, in the 1970’s there is no way this would’ve happened – it’s just not gonna happen. But you can see for dramatic tension, it worked to make this change.

I agree and also, the actors were all very good.

But you know, the most important thing doesn’t even have to do with the question of history. The important thing is that the film puts the viewer in the same relationship vis a vie the material, as the book puts the reader, so you feel that you’re drawn in with this fascination with Amin in the same way that Garrigan is and that was the key thing for me.

Except, perhaps the depiction of violence. The depiction of violence on screen is completely different on screen than it is on the page. You have a bit more control on the page of how you’re presenting it and what effect it’s having where on the screen it’s just there. But now, of course, it’s very tame in comparison to the stuff that’s out there.

I agree. I remember the days when television were so different. Looking back, it seems not too long ago, it was so much more sterile, less desensitized. Nowadays, its commonplace that people are trying to be overly “real” and seem to be in a continual flux of outdoing each other. The beauty of the written word is to leave a little to the imagination. What are your thoughts on this?

Frankly, how shocked do you want to be? I’ve been shocked enough in my life already. I like action and drama but hate those horror films where it’s nothing but gore. The big issue is, what effect is all of this having on us? We don’t really know yet.

How was it that you ended up writing one of the first reports on Al-Qaeda after 9-11?

I was in Zanzibar working on a travel piece when the US Embassy on Dar es Salaam was blown up. For someone like me who spent his life in Africa, principally, I knew this was something strange – very odd. So in 1998, I started investigating and found out a lot that people didn’t know and at that time, the US Intelligence community knew but the world at large did not; Al-Qaeda was not in the public consciousness. Because of this, I finished my novel, Zanzibar, about the embassy bombings. I was working at the Guardian and was at lunch and every journalist got a text asking them to return to the office immediately. But that first day, no one knew it was Al-Qaeda but within a few days, I ended up writing several pieces about them. It turned out that the people who were involved in the embassy bombings were on trial at the time this was happening so you could access a lot of information in real time. It was a very exciting time as the whole journalistic community was on this.

Do you approach pieces like travel writing differently than before?

I read a bit more before I go than I used to. I read other travel articles and find out what’s going on. I try to think of what the angle is going to be before I get there. It’s important to get a really clear brief from the commissioning editor of what they want. You often don’t get that so you have to really ask for it. The worst thing is when you write the thing you think they want and that’s not really what they want. So that’s something that I’ve found is really important.

What are some of the challenges of travel writing?

One of the challenges of travel journalism is to get enough of a sense [of the country] to feel that you’ve done both of your jobs of telling the truth and of providing the material that the magazine wants.

I was once writing a piece about the island of Socotra. This is a very beautiful island in the middle of two very unstable places and the issue here really, is water. You can see people cooking but at the end of the street, is a huge mound of empty water bottles which the photographer has to edit out of his shoot because that doesn’t fit with the kind of tourist idea [that is being sold] but for me, something as basic as water is something you want to get into the piece. Sometimes, there’s stuff you have to exclude, even if it makes you a bit uncomfortable. There’s a sort of ideology with travel writing that’s problematic. But, you’re not writing an environmental [or political] piece, you’re writing a piece that is going for tourists who are going on an adventure holiday in a really remote location and you want to try to attract them so sometimes, that kind of problem is hard to square.

What’s your favorite place?

Oh man. I think it’s a place called Mafia Island (it’s a Swahili word). It’s got nothing to do with the Mafia, it’s a tiny little island off the coast of Tanzania. There are a lot of political issues in Zanzibar that I feel a bit uncomfortable going there. On the African coast there are a lot of issues of hotel companies illegally buying land on the coast whereas Mafia Island is really small and you have the perfect Indian Ocean experience there so I recommend it.

How can someone become a travel writer?

A good way to get started is through inflight magazines. You can also try looking at brand magazines (like high end brand products) and write to the travel editor. Try pitching a particular idea but let them know you would be interested in other things they think might be more appropriate.

Some of these don’t pay much but they can help you build a portfolio. Once you have samples of your work, you can send that off to other editors and begin to build a relationship and a reputation with different companies. A lot of times, it’s not steady work so it’s always a good idea if you have income coming from elsewhere.

What about trying to write for big travel guides, like Lonely Planet?

Those jobs take all the fun out of travel. They are really all about the grind so if you can stay away from it, I’d recommend it.

What would you say to someone who would like to write but doesn’t feel they’re as talented as others?

Writing is for everyone. Innate talent, of whatever level, needs developing with practice.

What’s the best piece of advice you ever received with regards to writing?

Don’t try to put everything into one book.

Thank you, Giles. Your advice is duly noted.

A Note from the Editor

by Dawn Garcia

Like all writers, we struggle with the continual shift in what to write, how much ourselves to expose, whether we decide to admonish truth or swim into the realm of fiction. Knowing a writer and educator like Giles is out there, it’s a reminder that words are not mere antiquated letters strung together but instead, purposeful meanings dancing on a page like butterflies fluttering free. Be sure to continually check your nearest bookstore and peruse Foden’s many literary ventures. You won’t be at a loss for material, inspiration nor the nudge to delve into the crevices of your mind where the art of writing sets you free.

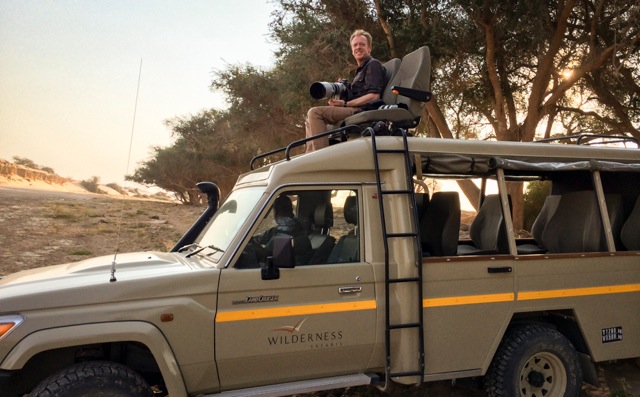

[separator type=”thin”]photos courtesy of Giles Foden and Philip Lee Harvey

1 Comment