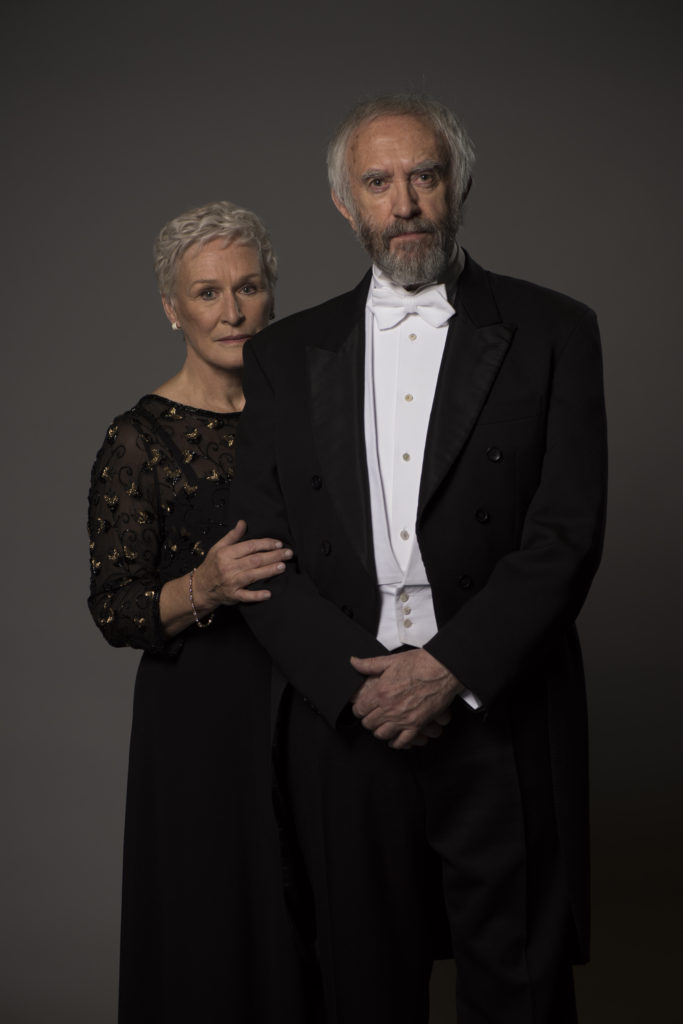

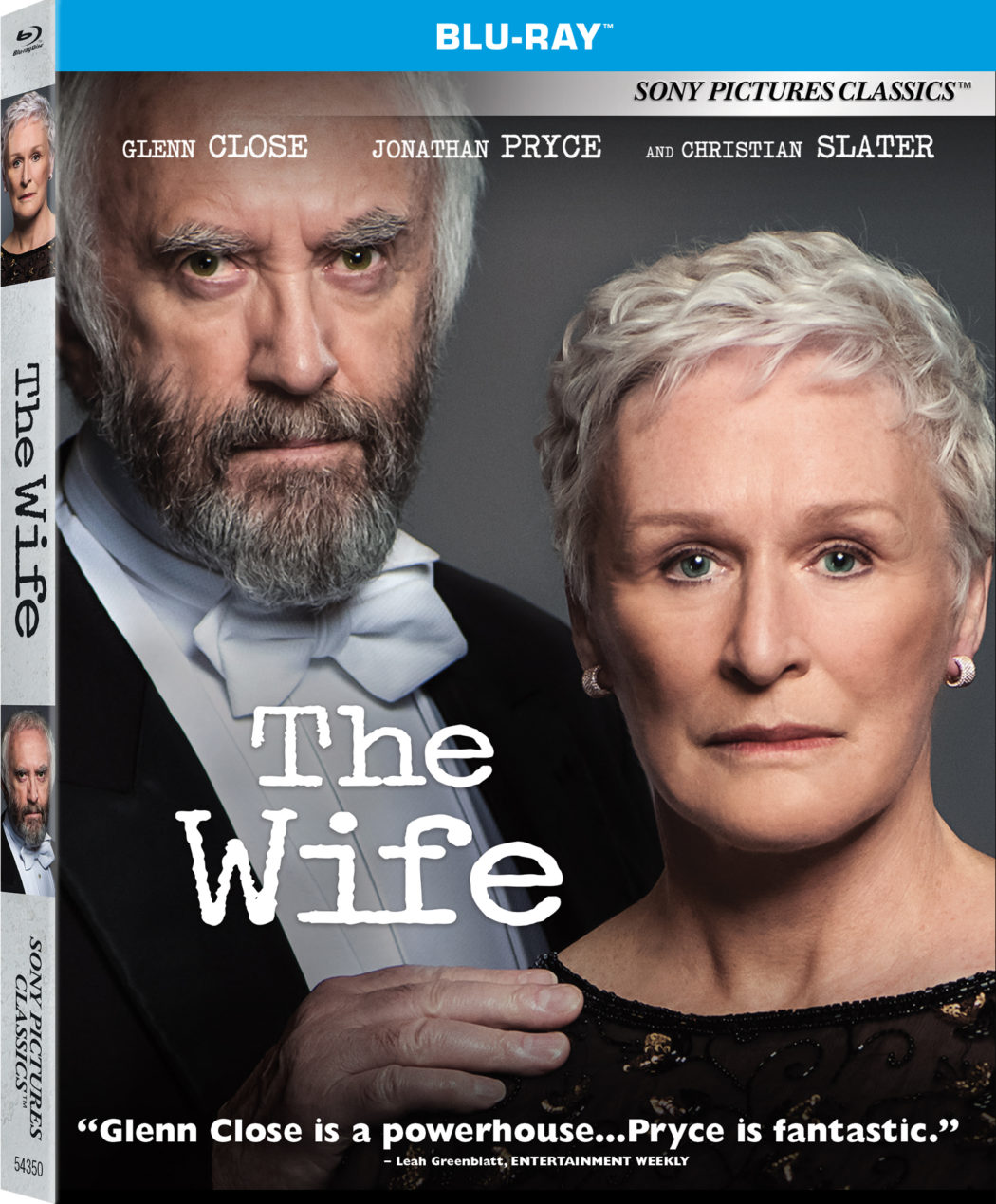

Once in a great while, the world of literature is given a gift. That gift is given by way of words so powerful and impactful, life as we know it becomes a bit broader. Now, if we’re lucky, that piece of literature is thoughtfully adapted for the screen and the results are equally sublime. Author Meg Wolitzer released her book, The Wife, in 2004 and in 2018, film lovers—and Glenn Close fans—got to see that story told in theaters thanks to screenwriter Jane Anderson and director, Björn Runge. With a compelling cast including Glenn Close (Joan), Annie Starke (Young Joan), Jonathan Pryce (Joe), and Harry Lloyd (Young Joe), the audience is taken into the dark and brilliant world of writers Joan and Joe Castleman. Married forty years, the two are a true juxtaposition of characteristics from elegance to being laid back, and while Joe is recognized as a great American novelist, Joan is the supportive, strong, dutiful wife standing beside him—but it’s not until Joe is awarded the Nobel Prize for his lifetime of work that the marriage begins to show it’s deafening cracks.

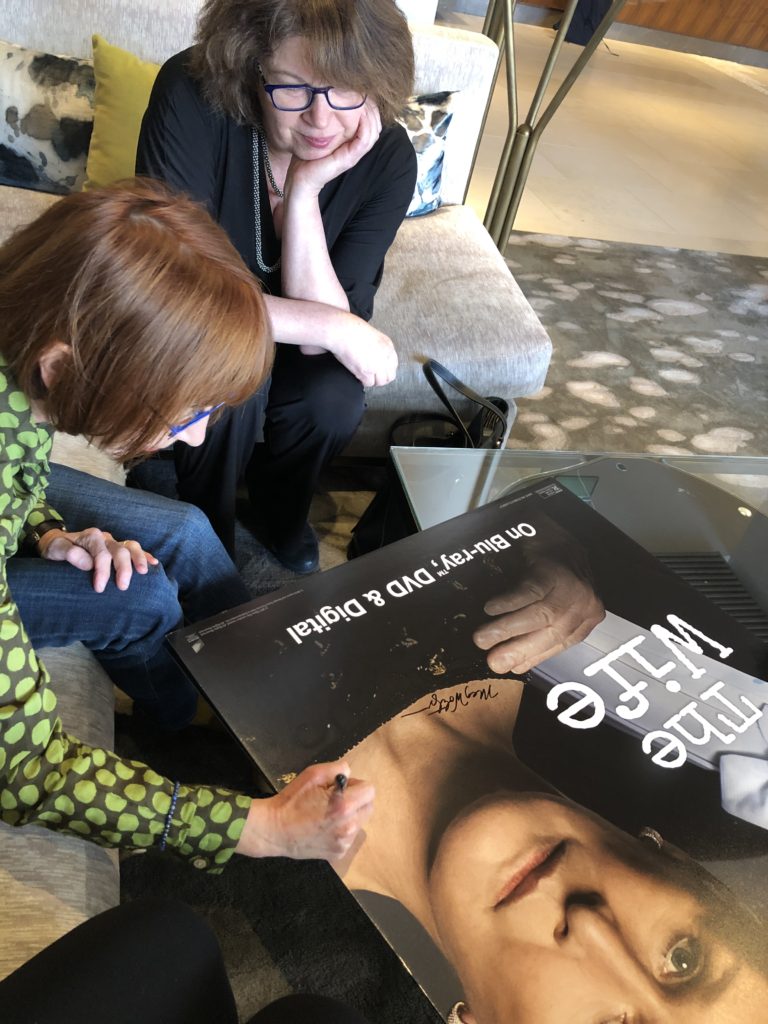

Having had the honor of being invited to an intimate afternoon with the women behind the film, the account of writing the book by Meg Wolizter, the telling of it on screen by Jane Anderson, and the truly profound performance by Annie Starke (who also happens to be Glenn Close’s daughter), I had an extraordinary opportunity to get personal and ask them about the project, their careers, and how this film and story has influenced them.

[separator type=”thin”]I love invention. I’m a child of a writer. – Meg Wolitzer

ĀTÔD: Women are finally getting our voices heard in this industry and female actors, writers, screenwriters, producers, journalists are no longer being seen as a sub-species. With all that’s happened as of late, how has that shift impacted this particular project and projects you do moving forward?

Also, while we have internal support systems with friends and family, do you have a strong support system in the industry?

Jane Anderson: I don’t know if all of you are aware that this took 14 years to make. It didn’t have the support of the industry. When I wrote the adaptation it was in 2004, back then the men who ran the studios after I wrote the script, they basically said to me, we don’t want to do a film starring a woman and we’ll never get a male actor to play in it. I had one agent say to me, “If I gave this to my male client, he would never forgive me.” And Rosalie Swedlin has worked for years to try to get this made and very smartly said, “Let’s go get money from Scandinavia and Europe because it takes place in Sweden, no American studio will finance this.” There’s a big joke at the top of the film – there are so many title cards at the beginning of the film and they’re all European! Only Jonathan Pryce, who is a brilliant actor, a Brit, and a theatre man saw this as a marvelous part, and not a part that was second to a woman—And he’s brilliant in it and a bit of an unsung hero in our industry.

So we just happen to have finally gotten the movie made right on the cusp of the #TimesUp movement, so we finally hit this magical spot where pissed off women are the new normal.

The universe worked in very interesting ways for us. – Annie Starke

As far as moving forward, the same thing is happening with films that are about African Americans and Asians, because the industry is being made to feel ashamed of itself for not giving voice to people of color and women. They’re starting to pour money into it. I think it will last because you know why? Things like “Black Panther” made the studios realize they could make money by being inclusive.

[separator type=”thin”] [columns_row width=”half”] [column] [/column]

[column]

[/column]

[column] [/column]

[/columns_row]

[/column]

[/columns_row]

The conversation then turns to marriage and past ideals versus present, and how those transform over time. As you listen to these women, it’s impossible not to find their strength, creativity, and sense of self to be warmly endearing. Annie is down-to-earth while dressed in a relaxed oversized pinstriped suit that seems to fit her youthful energy and graceful demeanor; Jane is composed and her glasses and fierce way of being fits her red hair, green sweater and well-spoken mannerisms that make you a believer in a movement that gives women in film a rather permanent voice; Meg is dressed astutely in all black, her sounding voice and educational foundation echoing in her command of the room, her devotion to the characters she creates, and her excitement when she speaks of writing is evident. Each woman gives a bit of insight on marriage and how its perceived in the film.

Annie: Live your life how you want, just don’t tell anyone else how to live theirs.

Meg: Just as people change over time, marriage changes.

The person you’re married to may feel differently in ten years. The way you are may have changed. The contract, the secret contract which I think all marriages have, may not look so good many years later and that’s what happens to Joan. The Nobel prize is too strong to not revisit the choices she’s made. In fact one of things I love in the movie is the “jumping on the bed twice”. It bookends the dynamics of their marriage so beautifully.

Jane: I took Meg’s character of David Castleman (Max Irons), Joe and Joan’s son, and I had him go with them on this journey to Sweden for the Nobel Prize. My theory being that if David hadn’t gone, maybe Joan could have made it through, but when you see your son being damaged by this agreement [marriage], I think that’s partly the motivation of why she had to explode.

Annie: She had lied to David in that moment when he asked her if she had written all of Joe’s work.

Meg: It’s so chilling.

The jumping on the bed was such a beautiful juxtaposition – I loved that because they start of saying “We Got Published” and end with “I Won the Nobel Prize” . I felt that both you and Glenn played this role with this sort of this quiet eruption and it was beautiful restraint. How challenging was that?

Annie: It was incredibly challenging. I think in our very in-depth effort to really understand Joan. I had to. I was very close to my grandma but my mom lived closer to feeling these societal effects and I’m fortunate to say I haven’t really felt that. She is an introverted woman, a keen observer of the world around her, the human condition. I also thin she’s shy which is a big thing – it was incredibly difficult but at the same time I understood exactly why she was that way. Björn, our director also knew this was something we really wanted to accomplish – this internal storm within.

I think of my grandmothers. My dad’s mom worked on the Manhattan Project and when she got pregnant, she got fired. And the other grandmother was part of the GE team that invented fluorescent lighting but as a woman didn’t get in on the patent. That same grandmother had this box of things from her life. My mother’s father was a very difficult man, and her mom was never encouraged to go to college or do something she wanted to but she was one of the most brilliant women I’ve ever had the pleasure of knowing. When she was older, she told us, “I haven’t done anything with my life” and to this day I have heart pangs when I think of that. This project made me think about the incredible women I have the pleasure of saying I’m related to. It’s an homage to these kind of women and I’d be a fool to pass that up.

Meg: The quiet was so amazing to me. The book is not a quiet book, it’s sort of loud. In the book she’s letting loose, letting it rip finally, and you are present for it. [To Annie] So when I saw both your performance and Glenn’s performance, it was so interesting how so much is in this quiet space. I grew up on Long Island and never imagined I’d have a Swedish director doing a film based on my book but it has this beautiful cinematic quality. And both actors convey that through their face. I was searching both of their faces and I think that’s very different through the reading experience.

Annie: My mom’s dad was a force. He was a wonderful grandpa but narcissistic, a successful surgeon and he loved his own story. I think my mom saw first hand growing up what my grandmother experienced and dealt with but professionally speaking, my mom has been very blessed by being given some very strong female roles so I think it can be said she trail-blazed the way for a lot of actresses. I remember the press asking about her show’s character on Damages asking her, “How do you do this, this woman is really awful” and my mom replied, “No, she’s just really good at her job. Would you say that though if I was a man?”

Jane: Writing for Glenn is a really exciting process because she doesn’t give up.

We then discuss symbolism in the book and the film, and what messages resonate from the film into their own lives.

Meg: I gravitate towards objects, and I always feel like you’re going to insert the object in the beginning and then it appears again in the end. You know what scene I love in the film is when they’re fighting and then they get the phone call that the baby is born. I love that change in their expressions and how quickly it shifts.

Annie: My favorite scene of both of them is when he accepts the Nobel Prize and all of a sudden you see her face. Because it’s the first time the presenter tells the audience about the impact her words have had on the world. You see her finally realize, “What is happening, what have I done, this is mine.” And you see at the same time you see a look on Joe’s face of, “This isn’t mine, I don’t deserve this.” He knows how messed up it is that he’s up there on the stage and she isn’t.

Meg: It’s how writers feel toiling around in the dark, and you have no idea the impact your work is going to have on the world or has on people until it’s out in the world.

Jane: It’s the basic condition that screenwriters have. We’ve spent six months to two or three years crafting this thing and then the directors are given all of the credit. And of course the Writer’s Guild has been trying to fight this for years, giving credit to the writers—But it’s a common feeling that us screenwriters have.

I want to ask Jane and Meg, where are you in the book and where are you in the screenplay?

Jane: The perpetual feeling of doing enormous amounts of work and not being recognized for it—that’s what appealed to me when I read Meg’s novel. And it was a time, like I said before, where there was a lot of sexism and my career as a director was much harder. I loved it because Meg writes about deep and angry things without being ernest of bitter, and I found it to be a funny, interesting way to express a deep frustration I was having.

Meg: I wrote an essay for the NY Times book review in 2012 called “The Second Shelf” which was sort of a riff on the title “The Second Sex” and I was talking about—in this essay—the different ways that men and women literary fiction writers were treated and I opened with an anecdote of a party I had been to. A man came up to me, and first of all asked the one question you never ever want to ask a writer: Would I have heard of you?

I realized eventually that there is really only one good answer to that question which is: In a more just world. I told him I wrote about marriage, sex, sexuality, family, adolescence, relationships, power, sexism and his eyes rolled up into his head and he said, “You should talk to my wife, she’ll be interested.”

Look, sexism still exists. We’re still living in a world where you can see it and you can feel it, but I feel powerful when I write and there are powerful books by women that get enormous acclaim like Toni Morrison getting the Nobel Prize. You have to take the long road.

Annie: I think the dialogue is getting stronger.

Meg: I think the dialogue right now at this moment is urgent and is loud, but for me as a fiction writer-it’s different from writing a polemic. There’s a great Emily Dickinson line, “Tell all the truth but tell it slant.” Slant is the way to get things across. When you ask where I am in this book, I’m everywhere in this book. People say to writers write what you know. I think it should be, write what obsesses you. In the case of this book, I was thinking for a long time about power, marriage, what its like to be a woman in a male world. It was made for me to do and even though I’m not Joan, I had to breathe into her at every moment.

Jane: I think we should talk about the men that helped make this film like Björn. I think its important as women, we’re gaining our artistic and professional power that we don’t make men feel like schmucks or like they should no longer have a voice.

The artistic world is not a zero sum game

There are beautiful important stories told by men—about men. We just want a little more parody but we don’t want to silence the male voices.

Annie: We want it to be mutually beneficial.

Their character names, Joe and Joan? Was it intentional of the polarity or because they’re one in the same?

Meg: I never try to do things to be fully symbolic. I try to be as intuitive as a I can. I first saw her as Joan. I loved that it was a single syllable and not a flowery name and then later, Castelman which has the whole king thing going on but once I got Joan—it’s kind of like If You Give A Mouse a Cookie. With Joan, how far behind can Joe be. They were interchangeable. Like if you say it fast you can’t tell whose name is uttered. Joan or Joe.

[separator type=”thin”]And with that, the afternoon with these truly extraordinary women comes to an end. Celebrating the Oscar Nomination for Best Actress, Glenn Close, and the release of the film onto DVD/BluRay, “The Wife” is a film everyone must see. Not only is it shot pristinely, the silence of the film in its moments of power are so grandiose in nature that you begin to blur the line of reality versus fiction. Annie Starke as young Joan Castleman gives the kind of soulful performance that you hope to see on screen more often. Together she and off-screen mom, Glenn Close give a performance that will find its way into you in such a way, it’s as if they are unleashing visual prose one composed, introverted, eruptive nuance and expression at a time.

As for its message of females taking their place in the world, being inclusive is something the industry has long since known, but now they have no choice, they have to forgo that mindset. They can no longer pretend there aren’t cultures of men and women whose stories deserve to be told. Films such as “The Wife” are a truly remarkable reminder that what we need are more female-driven films with stories that no longer keep our strengths and wonder in the shadows, but allow those attributes to shine alongside the men who have been in the spotlight for so very long.

[separator type=”thin”]Photos courtesy of Graeme Hunter Pictures and Sony Pictures Classic

1 Comment