Mexican cinema is one of the most prolific and mesmerizing realms of filmmaking. From small visionaries to Oscar winners, the world seen through the Mexican lens is one to celebrate.

We believe the power of story exists in many forms. The Golden Age of Mexican Cinema brought Mexican film to the forefront, and while the nostalgia of times passed continues to leave an indelible mark, modern cinema is quickly rising in the ranks. But in order to appreciate where we’re heading, it’s important to remember where it began. In an article titled, The Golden Age of Mexican Cinema: A Short History, Lauren Cocker writes, “Mexican cinema in recent years has gone from strength to strength, but it’s yet to live up to the Golden Age of Mexican Cinema that spanned from 1936-1959.

During this period, Mexican cinema took centre stage as the epicentre of commercial cinema in Latin America, and began to be recognised on an international level.” She includes the Época de Oro del Cine Mexicano. “It’s widely accepted that the Fernando de Fuentes films Allá en el Rancho Grande (1936) and Vámonos con Pancho Villa (1936) set the wheels in motion for what would become Mexican cinema’s Golden Age. María Félix’s breakout role in Doña Bárbara (1943) finally allowed women to play characters other than the submissive wife and mother, plus her star turn in Enamorada (1946) cemented director Emilio Fernández’ status as one of the key figures of the period.”

Maria Félix wearing a snake bracelet among other jewels in Venice in 1959. Photo: Getty

From femme fatale icon Dolores del Río who became a Hollywood success story, to Jorge Negrete, Mario ‘Cantinflas’ Moreno, German ‘Tin Tan’ Valdes, prolific director Fernando de Fuentes, (whose Mexican Revolution films, El Prisionero Trece, El Compadre Mendoza, and Vámonos con Pancho Villa launched the notoriety of Mexico’s film industry), Emilio Fernández, Miguel Contreras Torres, Ismael Rodríguez, Dolores del Río, María Félix, and Spanish writer Luis Buñuel, Mexico’s Golden Age made cinematic history. Growing up with a grandfather who was born in Chihuahua, México, he told me stories of México, including how Poncho Villa saved he and his sister’s lives and took them safely to his Aunt’s house where they were raised to escape the Federales.

You see, my own childhood was peppered with grand tales told by my grandfather about growing up and how much he loved and missed México, to how he found my grandma when he heard her singing on the radio in his small town. I was always enamored with the intrigue of a history so rich in color and literary texture, and perhaps he’s why I love infusing everything with that same grandness. My grandparents loved Telenovelas but even moreso, they loved movies. And we watched as many as we could. I remember watching Si usted no puede, yo sí and even though I didn’t speak much Spanish, remember laughing with my grandparents. My heritage begins when my grandparents (Méxican and Spanish) emigrated here in the 1940’s. My grandfather joined the Airforce, fought in the war and was a very high ranked gunner, and my grandmother worked for Max Factor as Max’s secretary. The stories they would retell over and over would find their way to my young, impressionable ears which is maybe where my love of film and television truly began.

My childhood was abundant in black and white films in multiple languages, but something about the romantic way even revolutionary films were made in México’s heyday lingered long after the years passed. And then, well into my twenties, I began my own descent into the world of foreign films. And I discovered Belle de Jour, Yin shi nan nu, Mujeres al borde de un ataque de “nervios”, Indochine, Before Night Falls, Fa yeung nin wah, Cinema Paradiso, and El laberinto del fauno. My entire world opened in ways I couldn’t have possibly imagined.

Hollywood Insider Pan’s Labyrinth, Guillermo Del Toro

That is when I discovered both Guillermo del Toro and eventually, Alejandro González Iñárritu. Two filmmakers whose impact on the world of cinema—and me—continues to astound. Guillermo del Toro was born in Guadalajara, Jalisco, México. Raised by his Catholic grandmother, del Toro’s fascination with filmmaking began in his early teens. As he got a little older, he became intrigued by makeup and effects and learned about it from the legendary Dick Smith, which led to del Toro making short films. At the age of 21, del Toro executive produced his first feature, Dona Herlinda and Her Son (1985).

Del Toro spent almost 10 years as a makeup supervisor, and formed his own company, Necropia in the early 1980s. He also produced and directed Mexican television and taught film. However it is his film, Pan’s Labrynth (El laberinto del fauno) that catapulted his career in the states when the film was nominated (and won) three Oscars for Cinematography, Makeup, and Art Direction. Pan’s Labrynth is perhaps one of the most powerful visual stories that seamlessly blends fantasy, drama, love, trauma, displacement, abuse, and magic. Del Toro is a filmmaker who exists in the truly fantastical place where dreams intersect with reality.

The way he tells story is gripping, artful, poetic, deeply profound, and boundary-pushing as evidenced in Pan’s Labrynth and The Shape of Water. After having seen Pan’s Labrynth (El laberinto del fauno), it became clear that his gift of storytelling transcended me and is when I felt that swell of youthful curiosity and the belief that magic really does exist … and that magic lives and breathes in movies. It was a reminder of the moments growing up when a film could transport me entirely to a place where I no longer existed in reality and instead became fully immersed in the art of cinema. I remember the feeling of sheer enchantment sweeping over me as he spoke on the panel of filmmakers years later. His work is profoundly magical, honest, and rooted in his Mexican upbringing.

When it comes to Mexican filmmaker Alejandro González Iñárritu, his style of filmmaking is stylized and incredibly gut wrenching. Unapologetically rooted in exposing the human condition, González Iñárritu takes tremendous risks in his films. The continual theme is one that exposes the core of who we are fundamentally as human beings. Using the human psyche to unravel the hero’s journey, his films have a darkness to them that inevitably make then hauntingly beautiful. And he never is one to take the easy route to accomplishing whatever cinematic realm he strives to create.

González Iñárritu is the first Mexican director to be nominated for the Academy Award for Best Director and by the Directors Guild of America for Best Director. He is also the first Mexican-born director to have won the Prix de la mise en scene or best director award at Cannes (2006), the second one being Carlos Reygadas in 2012. His six feature films, ‘Amores Perros’ (2000), ’21 Grams’ (2003), ‘Babel’ (2006), ‘Biutiful’ (2010), ‘Birdman’ (2014) and ‘The Revenant’ (2015), have gained critical acclaim world-wide including two Academy Award nominations. Alejandro González Iñárritu was born in México City. At the age of 17, he crossed the Atlantic on a cargo ship and by 19 worked his way across Europe and Africa. He has said that these experiences had a deep influence on him as a filmmaker. Many of his films are set in the places he visited on those journeys at such an impressionable age.

González Iñárritu returned to México City and majored in communications at Universidad Iberoamericana. He began his career as a radio host on WFM in México in 1984, and by 1998 he was the director of the radio station. During that time he had interviewed rock stars, airing live concerts and WFM became the number one radio station in México. From 1987 to 1989, he composed music for six Mexican feature films. It’s no surprise that he believes music was his first love and has inevitably influenced him even more than film.

González Iñárritu created Z films in Mexico with Raul Olvera in the 90’s and that’s when he began writing, producing and directing television and inevitably, film. He studied under Polish theatre director Ludwik Margules, as well as Judith Weston in Los Angeles. His first film in the states that put him on everyone’s radar is Amores Perros. A film with a story that exposes the world of dog fighting while simultaneously making a brutally honest statement about the dog fight humans are in every single day. After that, he wrote and directed several projects, but it is Oscar nominated and winning films Biutiful, Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance), and The Revenant that cemented his fate as one of the most formidable filmmakers in the United States and México.

Having the pleasure of watching Birdman at The Theatre at Ace Hotel in downtown Los Angeles live while the brilliant Mexico City jazz drummer Antonio Sánchez played in unison with the film, the power of González Iñárritu’s ability to bring the page to life while infusing the potency of music is undeniable. He is a life force that exudes conviction, passion, and an emotional depth necessary to visual storytelling.

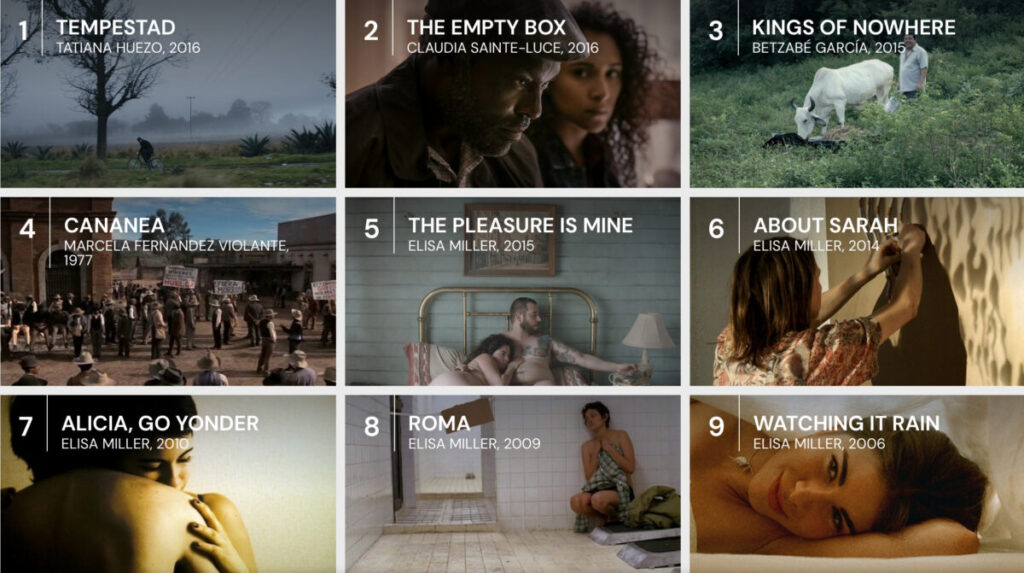

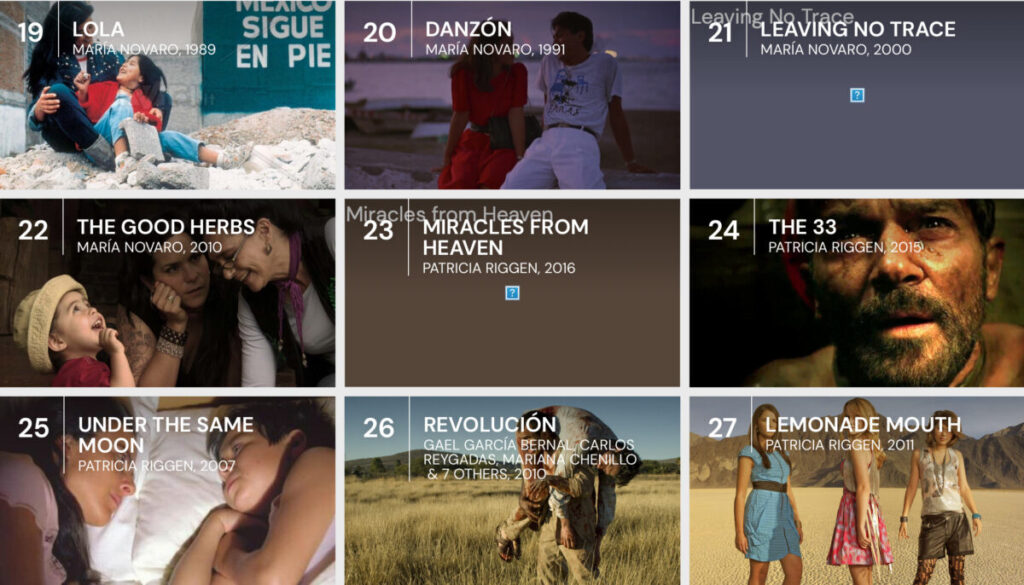

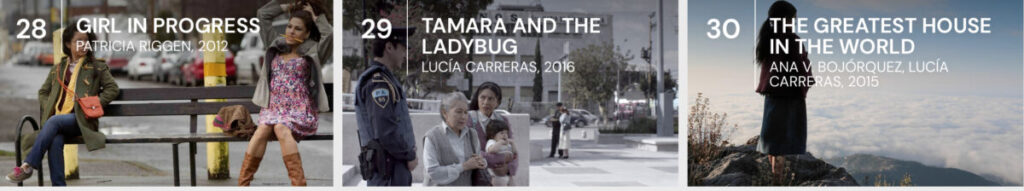

That said, while the men above are phenomenal talents, I also want to highlight the abundance and importance of Mexican female filmmakers. Recent Mexican filmmakers you need to know are Issa Lopez, Kenya Márquez, Maria Sojob, Tatiana Huezo, Betzabé García, Mariana Chenillo, Alejandra Márquez Abella, Patricia Riggen, Natalia Beristáin, and Lila Avilés. Riggen directed 3 episodes of the most recent Tom Clancy’s, Jack Ryan series with John Krasinzki and Aviles is known for her film, The Chambermaid.

We will be doing a second piece focusing on female Mexican filmmakers, writers, and producers next to expand upon the immense talent Mexicana filmmakers bring to the table. For now, below is a look at 30 (of 66) films directed by Mexican women from 1977-2016 (thanks to Angela Guerrero at MUBI for compiling this list).

Bios shared are from IMDb.

2 Comments