Climate change is most detrimental to women, showing great inequalities in its impact on our lives

When it comes to climate change and those disproportionately impacted by it, studies continue to show that women are hit the hardest. As we make our way through the twenty-first century, climate change is by far our greatest and most crucial issues at hand. It directly affects women, people of color, and generations, age, classes, and usually low-income groups—and the urgency to address it is not going away.

Gender is one of the stories of climate change that is not garnering enough attention, which only amplifies the sense of urgency while also casting a massive shadow over sexism that seems to be playing itself out in plain sight. From droughts to rising temperatures, the issues facing women on a massive scale stem from old mindsets and dangerous rhetoric. The continual plight women are facing by not being given access to the resources they need is further proof of a societal conditioning deeply embedded into communities and governments across the world.

According to Balgis Osman-Elasha, Principal Investigator with the Climate Change Unit, Higher Council for Environment & Natural Resources, Sudan; and a lead author of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the people who are already most vulnerable and marginalized will also experience the greatest impacts. She reports that the poor, primarily in developing countries, are expected to be “disproportionately affected and consequently in the greatest need of adaptation strategies in the face of climate variability and change”. Those also affected are men and women working in natural resource sectors, such as agriculture. That said, it is women who are increasingly being seen as more vulnerable than men to the impacts of climate change, mainly because they represent the majority of the world’s poor and are proportionally more dependent on threatened natural resources.

Her reports clarify that the differences of the sexes is seen in their differential roles, responsibilities, decision making, access to land and natural resources, opportunities and needs based on their gender. On the global stage, women have less access than men to resources such as land, credit, agricultural inputs, decision-making structures, technology, training and extension services that, had they access to, would enhance their capacity to adapt to climate change. But that isn’t the case.

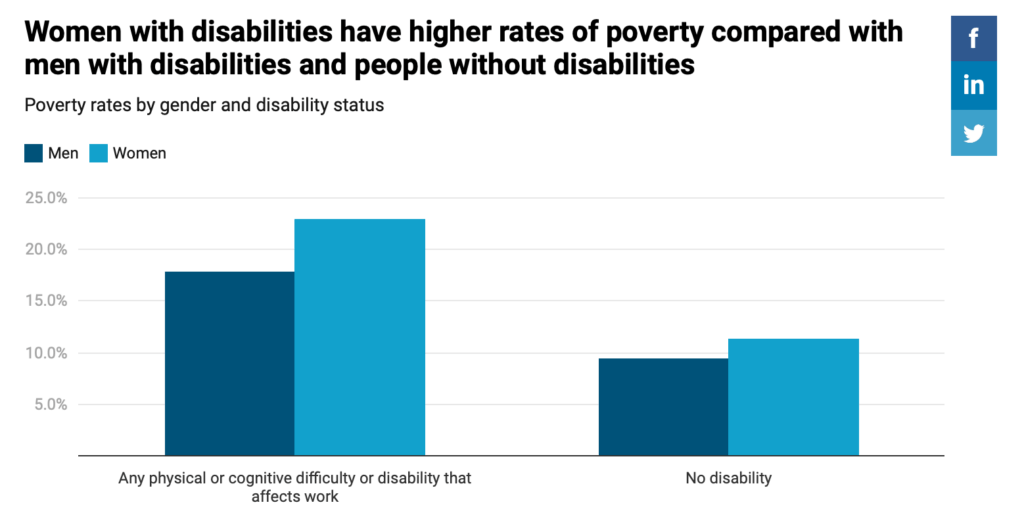

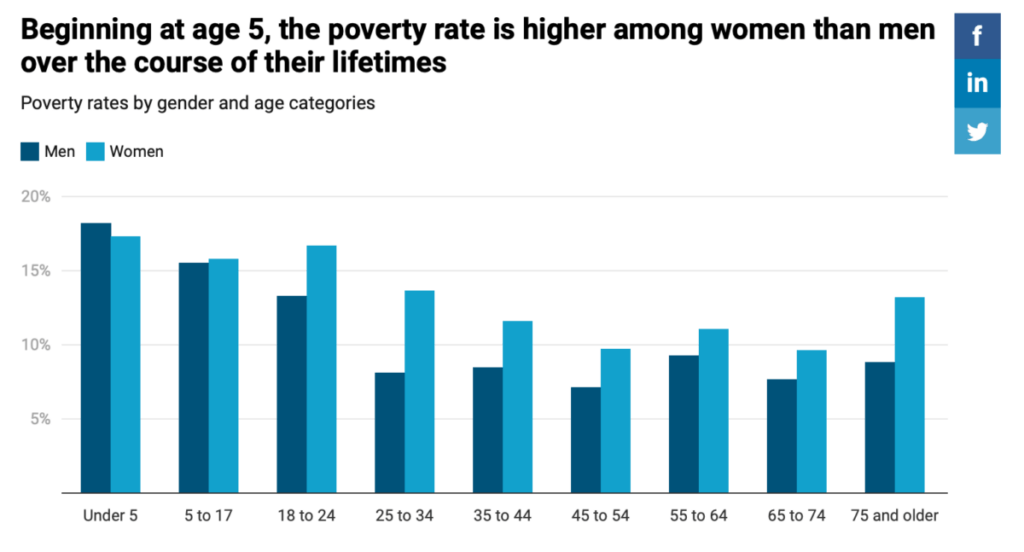

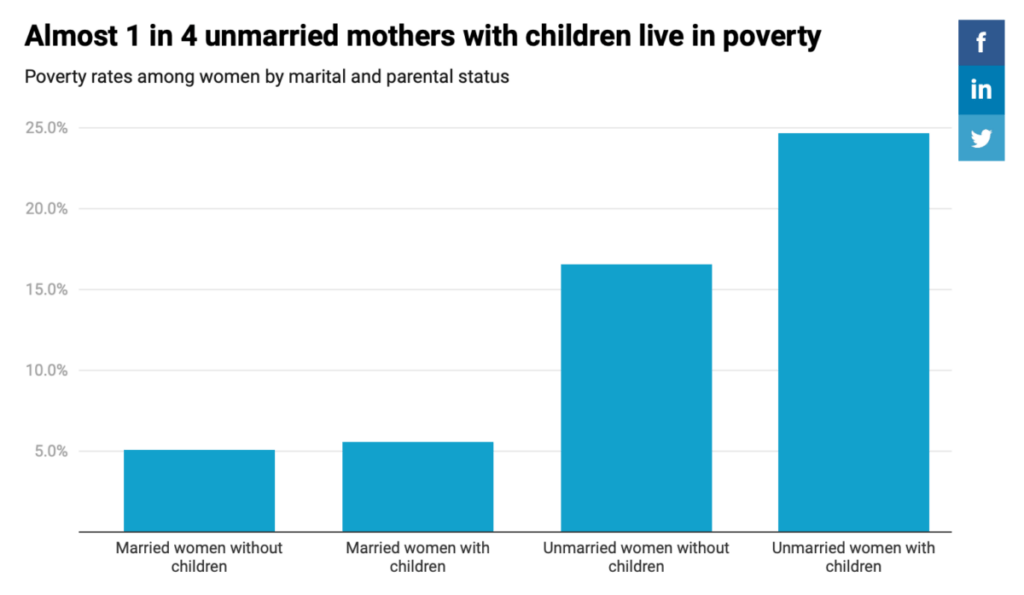

In research done by the U.S. Census Bureau there are more women in the United States living in poverty than men. According to U.S. Census Bureau data, of the 38.1 million people living in poverty in 2018, 56 percent—or 21.4 million—were women. The coronavirus pandemic has put individuals and families at an increased risk of falling into poverty in the United States, as they face greater economic insecurity, due in large part to unprecedented unemployment that has disproportionately affected women.

The following information is from AmericanProgress.org

The federal poverty line is an imperfect measurement of poverty

The poverty estimates included in a fact sheet document shared in American Progress are based on the federal poverty line, or the minimum annual income for individuals and families determined by the U.S. government to pay for necessities. In 2018, the poverty line was set at an annual income of $13,064 for a single individual younger than age 65 and $25,465 for a family of four with two adults and two children.

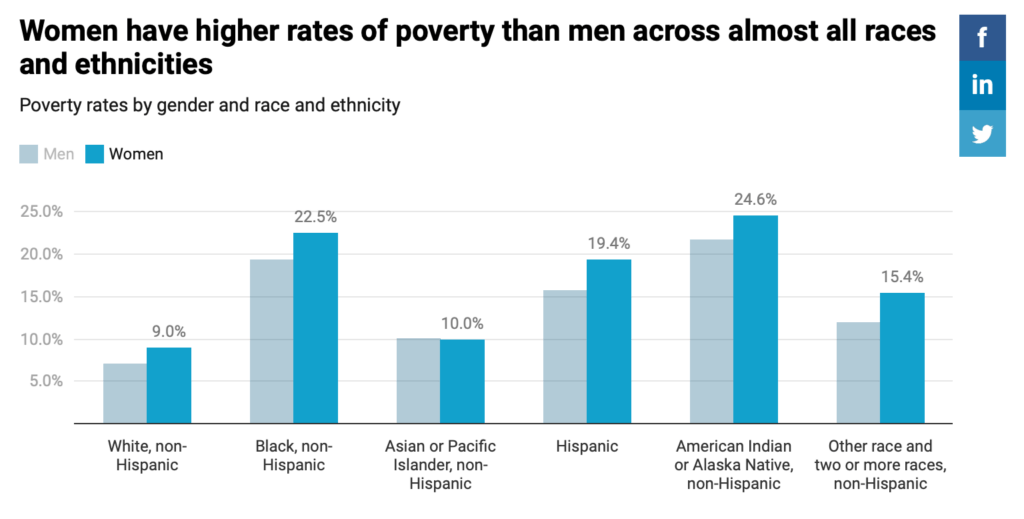

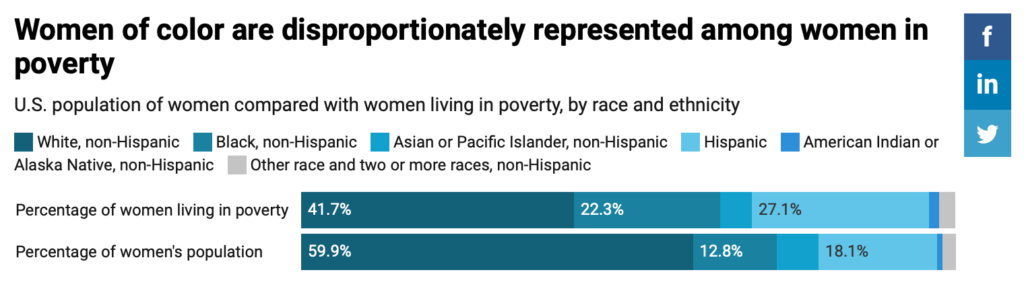

The effects of sexism and racism on institutional structures and across society limit the employment opportunities available to women, availability of caregiving supports, access to public social assistance programs, and more, leading to higher rates of poverty among women, particularly women of color, compared with men. Some of the interrelated causes include the following factors.

The gender wage gap

On average, women earn less than men—and the wage gaps are wider for most women of color. Based on 2018 U.S. Census Bureau data, women working full time, year-round earn an average of 82 cents for every $1 earned by their male counterparts. For every $1 earned by white, non-Hispanic men, Latinas earn 54 cents, AIAN women earn 57 cents, Black women earn 62 cents. Asian women overall earn about 90 cents, however women belonging to certain Asian subgroups experience much larger wage gaps. Not only do more women than men struggle to cover everyday expenses due to the gender wage gap, but the gap compounds over a lifetime, meaning women end up with fewer resources and savings than men. This represents a significant factor contributing to the gender disparity in poverty rates among women and men age 75 and older.

The gender wage gap is driven by a host of factors, including, but not limited to, differences in jobs or industries worked, hours worked, and years of experience—although differences in occupation or education level do not explain away the gap. Discrimination based on gender, race, and/or ethnicity plays a significant role in the wage gap, depressing women’s earnings both directly, by paying women unequally, and indirectly, through sex- and race-based structural biases that can influence the jobs women hold and the number of hours they work.

We can strengthen climate action by promoting gender equality

- Women and men are experiencing climate change differently as gender inequalities persist around the world, directly affecting their ability to adapt.

- Regardless of women being primary stakeholders, educators, decision makers and experts across multiple fields, they are not given enough latitude in the decision making process that could lead to long-terms solutions for climate change, in spite of having proven track records that offer more equitable and sustainable solutions.

- Taking measurable steps towards gender equality benefits everyone, especially when considering that women playing a larger role in climate change would address the inequalities first hand. Continued progress towards gender equality at can help achieve successful climate action.

Osman-Elasha focuses on women’s vulnerability to climate change and the social, economic and cultural factors that play a key role. The information below is published in her research shared on the United Nations UN Chronicle website.

Seventy percent of the 1.3 billion people living in conditions of poverty are women. In urban areas, 40 per cent of the poorest households are headed by women. Women predominate in the world’s food production (50-80 per cent), but they own less than 10 per cent of the land.

Women represent a high percentage of poor communities that are highly dependent on local natural resources for their livelihood, particularly in rural areas where they shoulder the major responsibility for household water supply and energy for cooking and heating, as well as for food security. In the Near East, women contribute up to 50 per cent of the agricultural workforce. They are mainly responsible for the more time-consuming and labour-intensive tasks that are carried out manually or with the use of simple tools. In Latin America and the Caribbean, the rural population has been decreasing in recent decades. Women are mainly engaged in subsistence farming, particularly horticulture, poultry and raising small livestock for home consumption.

Women have limited access to and control of environmental goods and services; they have negligible participation in decision-making, and are not involved in the distribution of environment management benefits. Consequently, women are less able to confront climate change.

During extreme weather such as droughts and floods, women tend to work more to secure household livelihoods. This will leave less time for women to access training and education, develop skills or earn income. In Africa, female illiteracy rates were over 55 per cent in 2000, compared to 41 per cent for men.4 When coupled with inaccessibility to resources and decision-making processes, limited mobility places women where they are disproportionately affected by climate change.

In many societies, socio-cultural norms and childcare responsibilities prevent women from migrating or seeking refuge in other places or working when a disaster hits. Such a situation is likely to put more burden on women, such as travelling longer to get drinking water and wood for fuel. Women, in many developing countries suffer gender inequalities with respect to human rights, political and economic status, land ownership, housing conditions, exposure to violence, education and health. Climate change will be an added stressor that will aggravate women’s vulnerability. It is widely known that during conflict, women face heightened domestic violence, sexual intimidation, human trafficking and rape.

Improving women’s adaptation to climate change

In spite of their vulnerability, women are not only seen as victims of climate change, but they can also be seen as active and effective agents and promoters of adaptation and mitigation. For a long time women have historically developed knowledge and skills related to water harvesting and storage, food preservation and rationing, and natural resource management. In Africa, for example, old women represent wisdom pools with their inherited knowledge and expertise related to early warnings and mitigating the impacts of disasters. This knowledge and experience that has passed from one generation to another will be able to contribute effectively to enhancing local adaptive capacity and sustaining a community’s livelihood. For this to be achieved, and in order to improve the adaptive capacity of women worldwide particularly in developing countries, the following recommendations need to be considered:

• Adaptation initiatives should identify and address gender-specific impacts of climate change particularly in areas related to water, food security, agriculture, energy, health, disaster management, and conflict. Important gender issues associated with climate change adaptation, such as inequalities in access to resources, including credit, extension and training services, information and technology should also be taken into consideration.

• Women’s priorities and needs must be reflected in the development planning and funding. Women should be part of the decision making at national and local levels regarding allocation of resources for climate change initiatives. It is also important to ensure gender-sensitive investments in programmes for adaptation, mitigation, technology transfer and capacity building.

• Funding organizations and donors should also take into account women-specific circumstances when developing and introducing technologies related to climate change adaptation and to try their best to remove the economic, social and cultural barriers that could constraint women from benefiting and making use of them. Involving women in the development of new technologies can ensure that they are adaptive, appropriate and sustainable. At national levels, efforts should be made to mainstream gender perspective into national policies and strategies, as well as related sustainable development and climate change plans and interventions.

To learn more, please explore these studies, articles, and resources below:

OXFAM Climate Change & Women Fact Sheet

Gender and Climate Chage, IUCN

Gender Action, 2008. Gender Action Link: Climate Change (Washington, D.C.)

Third Global Congress of Women in Politics and Governance

This story, Climate Change’s Impact on Women Shows Great Inequalities, was originally published in part in our sister publication, Se Lever Magazine and has been republished here with permission.

1 Comment